Born in Italy in 1942, Anna Maria Maiolino is today acknowledged as a leading figure in contemporary art in Brazil and beyond. With her family, she left post-war Italy to settle first in Venezuela, and then Brazil, where her formative years were shaped by political instability and the Brazilian military dictatorship that held power between 1964 and 1985.

Closely associated with the 1960s Brazilian art movements of both New Figuration and New Objectivity, Maiolino developed a visceral artistic language characterised by experimentation with simple materials. Whether she is making gestural works on paper, film installations, photographs, or sculpture in paper, cement and clay and—from the 1980s—expansive clay installations, her work reflects on exile, language and memory.

Maiolino’s ANNA (1967)

Photo © the artist; courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth

In 2024, she won the Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement at the 60th Venice Biennale. This month sees the opening of her first solo exhibition in France, at the Musée Picasso, in Paris, which covers a career of more than 60 years and includes newly commissioned work.

The Art Newspaper: You have chosen to call your first institutional exhibition in France Estou Aqui (I am here). What is your thinking behind this title?

Anna Maria Maiolino: “I am here” serves as a response to a call, synonymous with “I am present!” It refers to the physical presence of my artworks in the Musée Picasso in Paris.

Do you want your exhibition to be in dialogue with Picasso and his work?

Art production depends on the historical period in which it was produced. There’s a huge age gap between me and Picasso, and you have to bear in mind the gender difference. That being said, we share a deep curiosity about the exercise of freedom and the use of experimentation. We use different techniques for the creation of our artworks in an effort to renew our language.

You were born and spent your early childhood in Italy, then moved to Venezuela, then Brazil. Between 1968 and the end of 1971 you were based in New York, before returning to Brazil where you now live. How has moving between so many places, languages and identities played into your work?

Since 2005, I’ve been living and working in São Paulo, Brazil. It’s clear that leaving Calabria to migrate to Caracas in 1954, as well as the other places in which I experienced different cultures and arts, left a lasting impression on my imagination and, consequently, my creation.

You have described yourself as “a completely contaminated artist”. What do you mean by that phrase?

I express myself in an exaggerated way, like a person from the south of Italy. In many senses, I feel contaminated by life experiences. With each change of territory, new feelings and emotions modified the past ones and on many occasions required that I quickly adapt to a new state, retaining the experience in my memory, which also feeds my creation. I was born into a large Italian family. I was one of nine children and the last one to be born, in 1942, during the Second World War. The memory of my childhood accompanies me as a living presence. My mother was 42 years old when I was born. She was born in 1900 and my father in 1896, so I’m an 83-year-old contemporary artist with an education from a different time, inherited from my parents’ experiences and from the significant presence of my eight older siblings. The cultures of the countries I got to know definitely left traces on my soul, so it’s safe to say that it’s not a question of contamination, but rather of poetic affections.

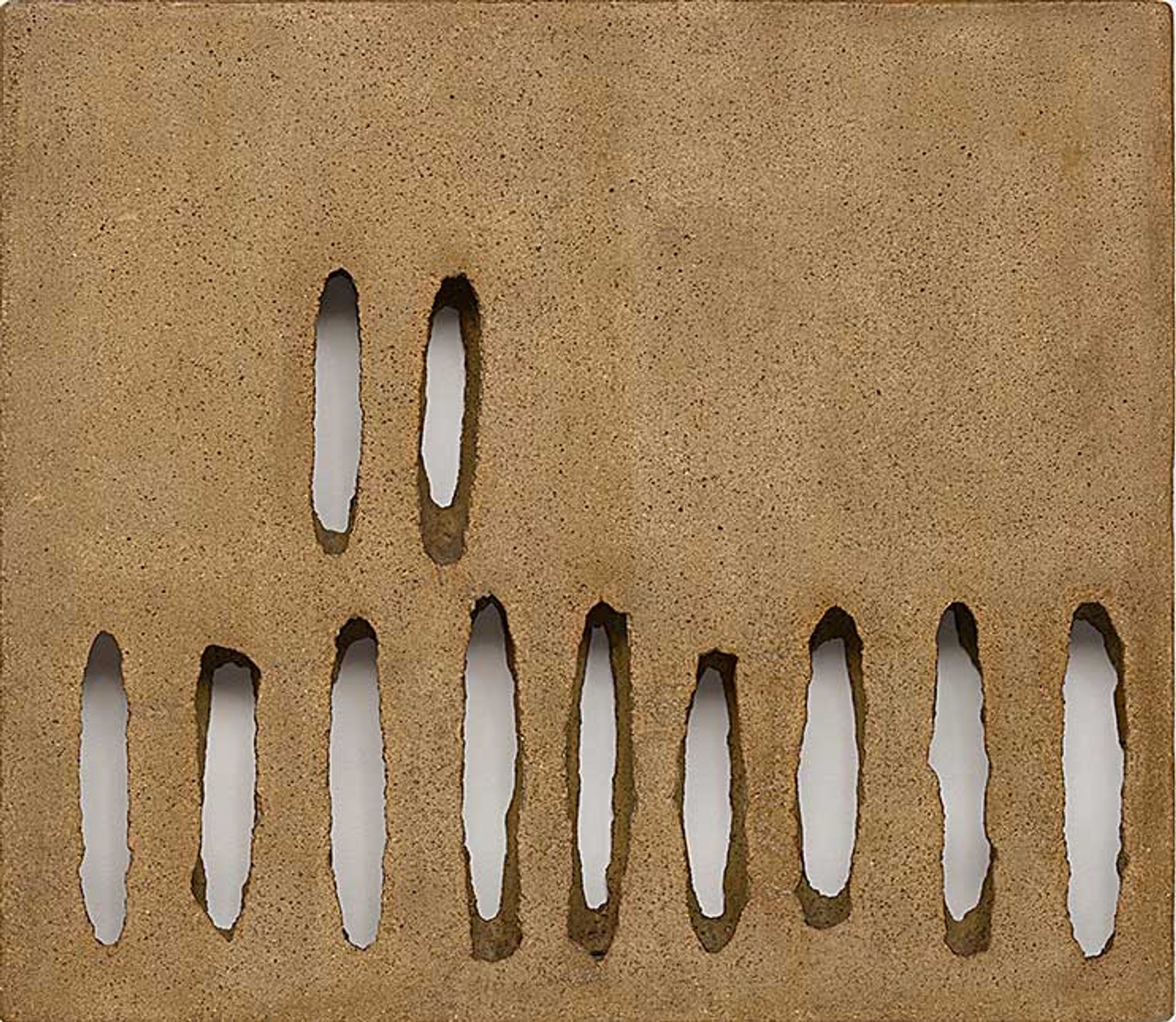

Untitled (1997) from the E o que falta (and what’s missing) series

Photo: Everton Ballardin © the artist; courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth

In 1989 you started using clay for the first time. Why did you turn to this material, which you continue to use, most notably in your Terra Modelada series? What are the qualities of clay that appeal to you? What purpose does it serve that other materials cannot?

Changing mediums during these 65 years of art means expanding my artistic discourse. Learning a new technique brings about a new internal dialogue between intellect and doing. In 1984, I found myself in a language crisis, searching for a common thread that would lead me back to optimism and to the discovery of a new future. To live in a new era in which I could say no to the dark moon of modernity and no to the here and now of postmodernity, I searched for a new solar period, a new birth, without fragments.

At the end of 1989, I came into contact with clay, and a new worldview emerged. Clay is earth, and earth is the paradigm of matter par excellence—it inherently carries the possibility of forms. That’s when I started making sculptural objects with the mould. Clay is fundamental for its tactile possibilities … and for the construction of time when working on the primordial mass of earth.

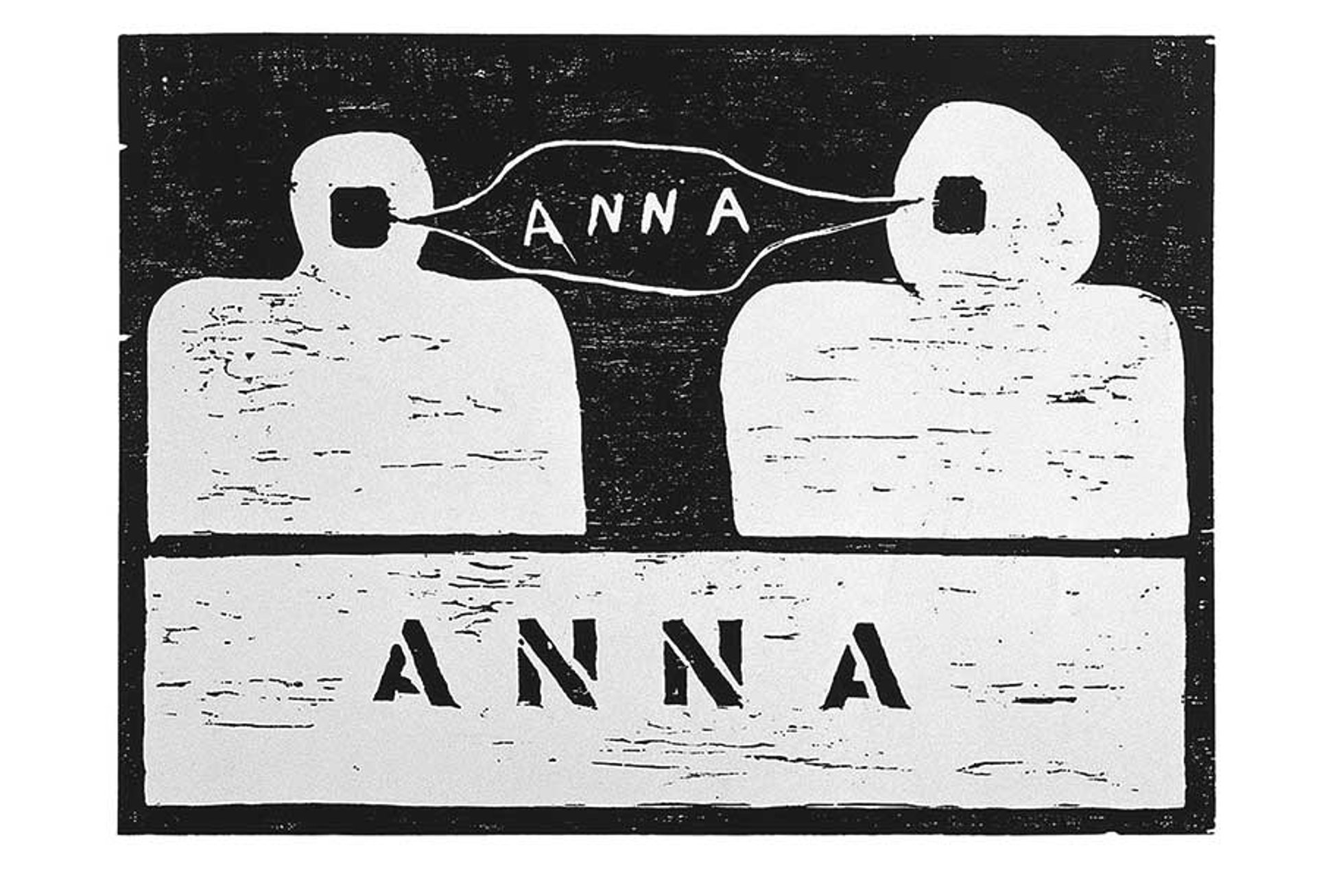

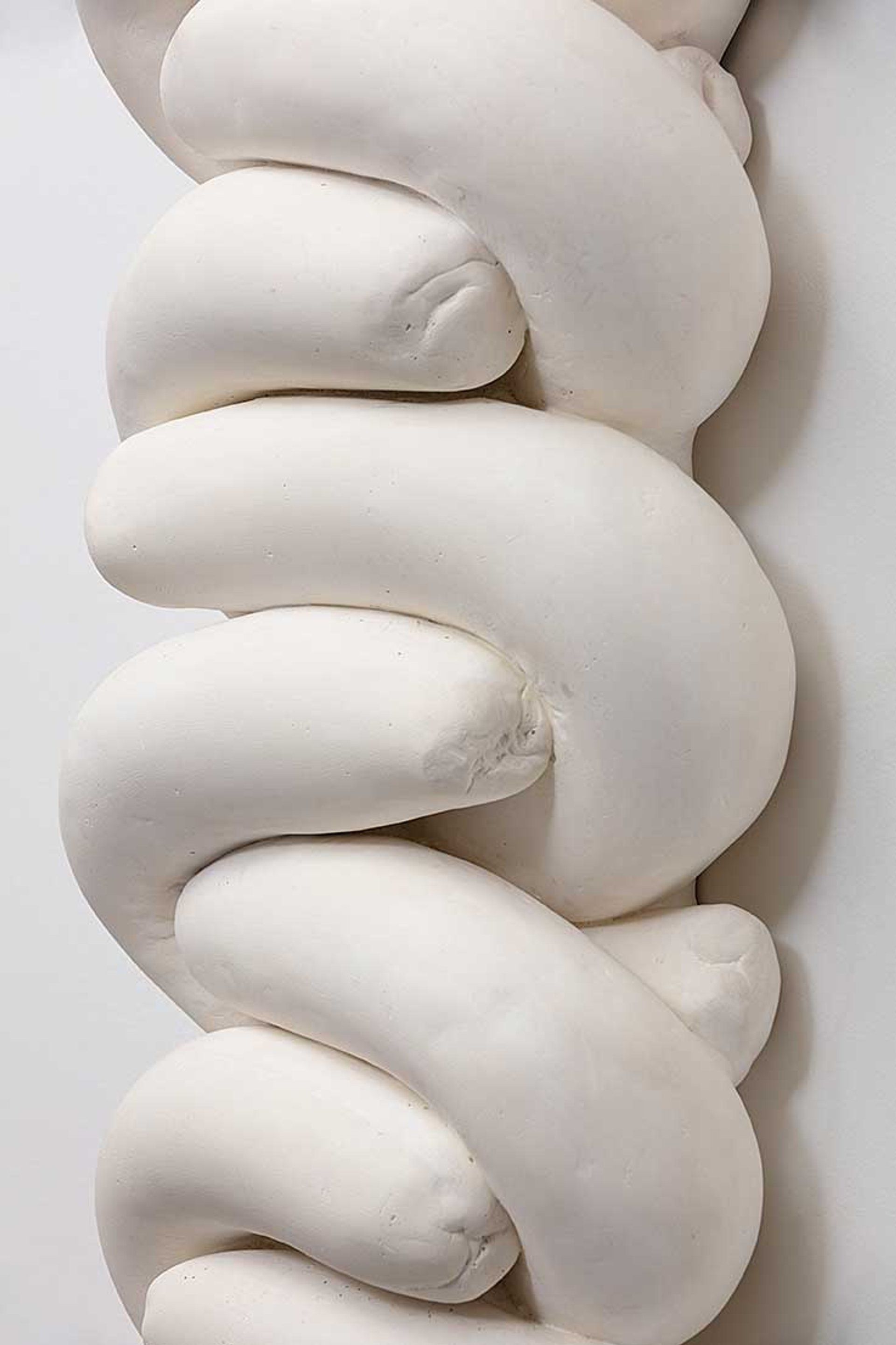

Round and round: loops, as in Untitled (1993), are a recurring motif in Anna Maria Maiolino’s work

Photo: Everton Ballardin © Anna Maria Maiolino; courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth

In 1994, I began to make large quantities of clay without firing it in situ. In these works, there is no use of the symbolic or the allegorical, since the intention is to be in a real space, not an illusory one, because they are what they are: working actions. By analogy, the viewer might find food or waste, but that’s not the point. All the wet masses have similarities, which could mislead the less attentive viewer. Nevertheless, these installations are metaphors for doing, for manual labour, that point to the presence of the pleasurable fatigue that conspires against the mass production and commodification of labour in our consumer society.

You have created a new site-specific installation for the Musée Picasso exhibition, titled In Principle, which is made from clay. What has influenced/inspired the forms that it takes?

The form of each new installation of Terra Modelada depends on the amount of clay and the space available. The concept of all of them is always the same: the demonstration of work carried out.

When our ancestors, the first hominids, stopped harvesting fruits with their mouths and developed the use of their hands, they turned the hand into the first tool. The skilled man who inaugurated our cultures emerged. The segments that compose In Principle are sculptural objects produced by the first basic hand gestures in the ordering of the clay and which connect us with the beginning, the origin.

An intense and active physicality runs all the way through your work. Bodily allusions repeatedly act as a cipher of meaning, whether as an instrument of resistance or a means of political/social critique in your early film and performances. Then there are all the bodily associations of the moulded, torn, rolled, kneaded—even seemingly excreted—forms in the more recent works, which all display powerful evidence of physical gesture. It is also apparent in your more recent films and performances. Why does this physical, organic presence remain so crucial to you?

I often say that my body speaks to me and that I’ve been listening to it since I was really young. Aware of its physicality, it is my body that gives me my identity and the various aspects of my life and creation. My body is my main instrument of creation, and in some aspects of my work, we have its presence. It is my body that connects with my mind-soul and my real surroundings, activating in me various human aspects that give rise to the different mental, poetic and political discourses in my work.

Language is another element that appears consistently in your work: in your own writings, object books, and the spoken words and texts evident in your work—the Musée Picasso catalogue also contains your poetic writings. Can you talk about the rich and various ways in which your work is deeply rooted in, and informed by, language?

I’m a curious person, and as a curious person, I’m not a professional; I’m an amateur who likes to experiment. In 1968, in New York, with two children aged two and four, the white sheet of paper became a territory for scribbling notes and short pieces of writing since it wasn’t possible to create larger works.

I feel that poetry is a cornerstone, a foundation for any creative act. It is a way of thinking about the world in an operational movement to transform what we experience into consciousness. I believe that poetry is inherent to the human being and that it drives the human evolutionary process. This makes me think with a certain delight about the primordial possibility of the existence of the “divine spark”. I am the daughter of an Ecuadorian mother and a Calabrian father. My mother studied to be an Italian teacher and was a great admirer of Dante, reciting him from cover to cover. When I was little, she would scold me with his verses. And my father emphasised the belief that to learn Italian well, it was enough to read Manzoni’s I promessi sposi three times in a row.

What did it mean to you to have won the Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement at the 2024 Venice Biennale?

It’s an encouragement to keep working as long as my body allows.

Physical activity captured in clay: Maiolino’s Untitled (1993) from the Cobrinhas No. 3 (little snakes)series

Photo: Everton Ballardin © Anna Maria Maiolino; courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth

You dedicated your Golden Lion to “Brazilian art, to the country that welcomed me”. What was it or is it about the nature of Brazilian art that you wanted to celebrate?

Arriving in Rio de Janeiro in 1960 was decisive in the choices I made about the paths along which I would build my artwork. The result of the encounter with Brazilian art, concrete and sensorial at that time, formed the basis of my work in the 1970s and, even more profoundly, the work I have been doing in recent years. It’s clear that, as an emigrant, I celebrate the Brazil that welcomed me and enabled me to pursue my poetics. Brazilian art is strong, pulsating and made through the creative act of freedom.

Biography

Born: 1942 Scalea, Italy

Lives and works: São Paulo

Education: 1960-61 Escola Nacional de Belas Artes, Rio de Janeiro; 1971 Pratt Institute

Key shows: 2019 Whitechapel Gallery; 2017 MOCA Los Angeles; 2014 Gwangju Biennale; 2012 Documenta 13; 1998 São Paulo Biennial 1967 MOMA Rio de Janeiro

Represented by: Hauser & Wirth; Galeria Luisa Strina; Galleria Raffaella Cortese

- Anna Maria Maiolino: Estou aqui (I am here), Musée Picasso, Paris, 14 June-21 September