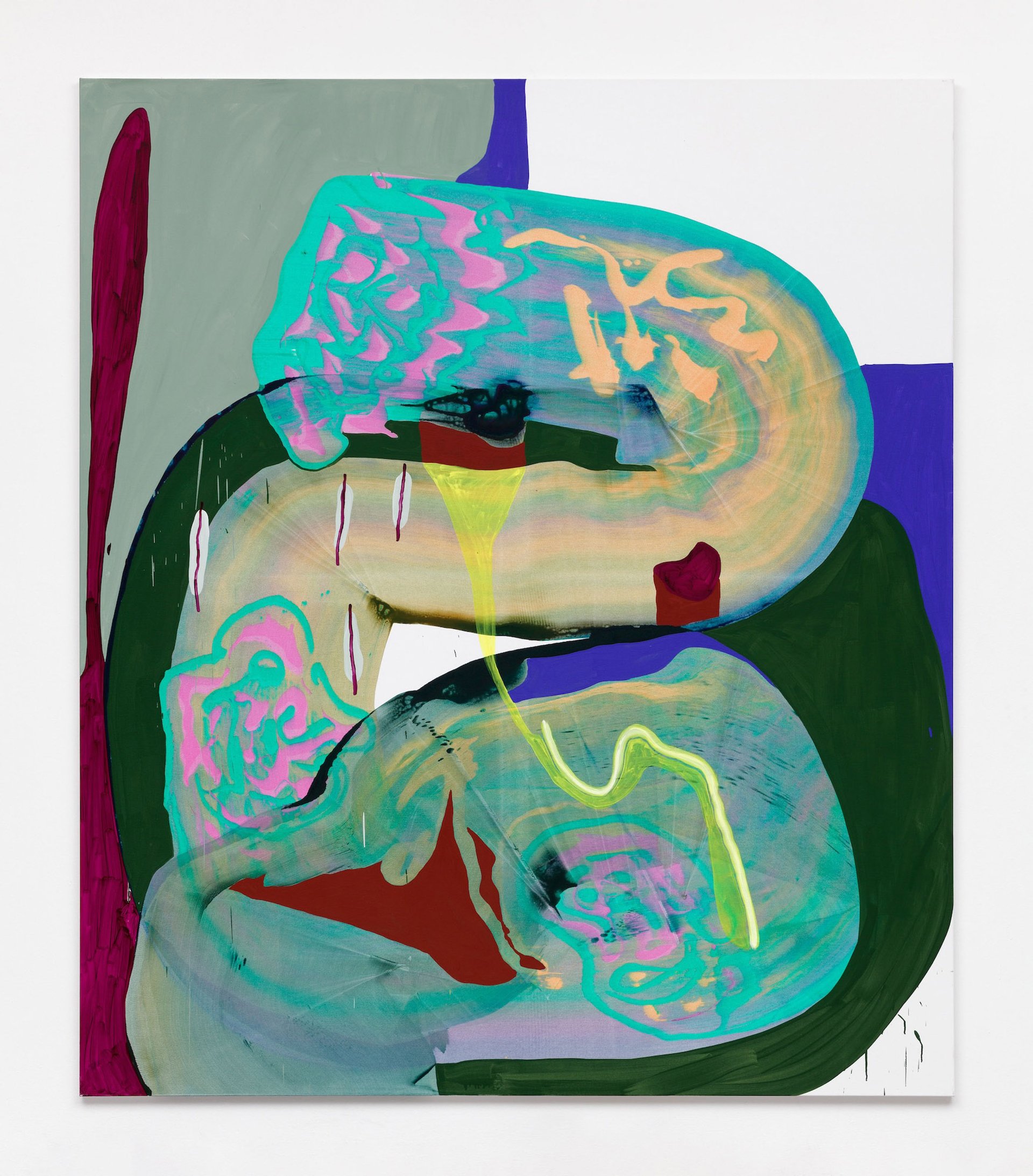

German representation at Art Basel this year is as strong as ever. While most participating galleries hail from the US (around 70 of them), Germany comes in second with more than 40. Since last year, Art Basel’s flagship fair in Switzerland has been led by Maike Cruse, who was born in the German city of Bielefeld. Works by many German artists appear in Basel as well—including Katharina Grosse’s large-scale, site-specific installation at the Messeplatz, as well as pieces by Martin Kippenberger at Galerie Gisela Capitain’s stand, Tim Eitel at Eigen + Art and Jana Schröder at Meyer Riegger.

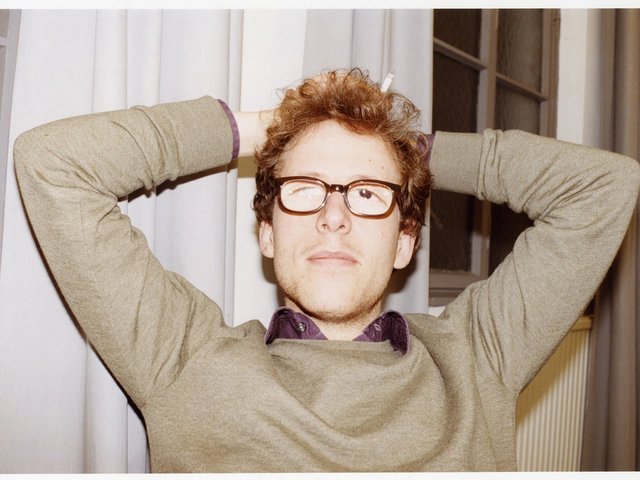

Maike Cruse, the German-born director of Art Basel’s Swiss edition Photo: Debora Mittelstaedt; courtesy of Art Basel

While Germany may lack mega galleries, it is home to several highly respected spaces—such as Galerie Max Hetzler—that originated in Berlin and have since expanded internationally, earning global recognition. Some of the world’s most sought-after living artists, like Gerhard Richter and Anselm Kiefer, are German. As are renowned collectors like Reinhard Ernst, Julia Stoschek and the Plattner family. Cruse describes Germany as “a leading arts ecosystem in Europe that plays a vital role in Art Basel in Basel as the fifth-largest art market in Europe, together with Switzerland”.

A ‘very stable’ market

Historically, Germany has always been a place of artistic innovation. The country’s relatively robust economic climate has also helped bolster its current standing in the global art world—a point made by the dealer Gerd Harry Lybke when reflecting on his home country’s strong presence in Basel. “Germany is less susceptible to the ups and downs of the art market,” he tells The Art Newspaper. “Compared to other locations, it is very stable.”

But this position may be at risk. Berlin’s cultural budget was cut by €130m (amounting to 12%) this year. An additional €15m in cuts is already planned for 2026. For years, Berlin has ranked just behind New York in the number of galleries represented at Art Basel. But this year, it slipped to third place, overtaken by London. Berlin has 28 galleries at the fair, while New York and London are represented by 50 and 35, respectively. But the gallerist Saskia Draxler of Nagel Draxler remains positive. “The avant-garde always inhabits the corners that are not in the spotlight,” she says. “Now that funding is decreasing, which many people rightly complain about, resilience is increasing and artists are becoming freer. Berlin is so much more than ‘cultural funding’.”

Jana Schröder’s FRONTRACK PSY LaVa (2024) at Meyer Riegger Photo: Johannes Bendzulla; courtesy of the artist and Meyer Riegger

Due to its unique history of territorial fragmentation, Germany is far less centralised than neighbouring countries like France. Several cities—most notably Munich and Cologne—have established themselves as strongholds of the German art world. Still, stepping into Berlin’s shoes will not be easy. “Munich has always been considered more of a ‘B city’ from an international perspective, and its outstanding institutions have not been able to change that,” Draxler says. But why should there be city rivalry anyway? Isn’t cultural comradery more beneficial?

Sprechen Sie Deutsch?

One might expect that with more than 60 galleries from Switzerland, Austria,

and Germany participating in Art Basel, the fair’s lingua franca would be German, the language of its host city. Yet the German-speaking art world embraced English long ago. Even when approached in German, some galleries automatically responded in English.

As everywhere, there are friends and enemies, collaboration and distanceSaskia Draxler, Nagel Draxler

When asked whether a special type of relationship exists among German-speaking gallerists at the fair, galleries’ answers reveal a rather reserved attitude. “As everywhere, there are friends and enemies, collaboration and distance,” Draxler says. “But of course, the competition is tough. However, you are not competing with the Germans in particular, but with the entire spectrum of gallery owners.” When asked about comradery among German-speakers, many galleries choose not to respond. The historical tensions between Germans, Swiss and Austrians are a familiar trope, but it appears that even among German galleries, there is not much closeness at Art Basel.

Monika Sprüth, one of the most prominent German gallerists, counters the question by aiming to trace German identity in the arts. “Berlin, in particular, shows how permeable borders have become,” she says. “Artists from all over the world live here and shape the scene. Visibility is created less through nationality than through international networks, discourses and institutional presence.”

Nina Hanz of ChertLüdde says: “While there may have once been more pronounced regional preferences, the art world has become increasingly globalised, and as a result, these national distinctions are becoming less significant.”

Umlauts in gallery names may be the last obvious giveaways of Germanness at the fair, making space for a borderless art community. Given recent developments in the art world (and the world at large), this attitude is understandable—yet it becomes contradictory when confronted with the political realities of topics like funding for the arts.

Gerd Harry Lybke, the founder of Galerie Eigen + Art, which was temporarily ousted from the fair in 2011 Felix Horhager/dpa/Alamy Live News

Germans are not typically known for public scandal, but in 2011 the unthinkable happened at Art Basel. Gerd Harry Lybke, the influential and widely respected founder of Galerie Eigen + Art, which had exhibited at the fair for many years, was suddenly not invited back. Art Basel’s selection committee, responsible for this decision, included six art dealers—three of whom were fellow Berlin gallerists. The incident exposed the undercurrents of rivalry and exclusion in the art world. In Germany, the public largely rallied behind Lybke. Today, Art Basel’s committee has grown to eight members with just one German representative, Bärbel Trautwein (who is a Berliner). Meanwhile, Lybke’s gallery remains as important as ever, and will be showing at this year’s fair.

Even though the issue seems long resolved, not one German gallerist was willing to comment on what happened 14 years ago. In this reaction lies the cultural difference between German and American mentalities: the American instinct is to smooth things over—apologise, make amends publicly and move on—while the German approach is often to carry on as if nothing happened, hoping the issue will quietly fade from memory.

Still, there is some praise reserved for fellow countrymen and women. Lybke says that what differentiates German collectors is “iconographic interpretation combined with a strong sense of history”. Philomene Magers, a co-owner of Sprüth Magers gallery, calls the German art scene “smart, critical and internationally connected”. Jochen Meyer of Meyer Riegger, showing at Art Basel for the 28th time this year, acknowledges the “strength and diversity of the German gallery scene and the consistency of German collectors”.

Germany’s nickname is “the country of poets and thinkers” (Das Land der Dichter und Denker), after all. And most German gallerists say that Art Basel remains their favourite art fair—the “highlight of the year”, as Draxler puts it. Comradery or not, it must all be well worth it in the end.