From 1936 to 1939, Spain endured a brutal civil war won by Nazi-aligned fascists. This led to mass exile to France, mostly in the south, eventually numbering half-a-million people. When France surrendered to the Nazis in June 1940, Spanish socialist refugees were interned and many were deported along with Jews to concentration camps. Meanwhile, patients languishing in French psychiatric institutions were barely fed under wartime austerity; 40,000 either froze or starved to death, a little-known fact.

This anthology, which sprang from an exhibition at the American Folk Art Museum in New York (12 April-18 August 2024) ending a four-city international tour, concentrates on one asylum in Saint-Alban-sur-Limagnole in the Lozère region of France, and on the Catalan psychiatrist Francesc Tosquelles (1912-94), whose approach to treatment and the inclusion of art in that process brought compassion to a world driven mad.

Haven for therapy

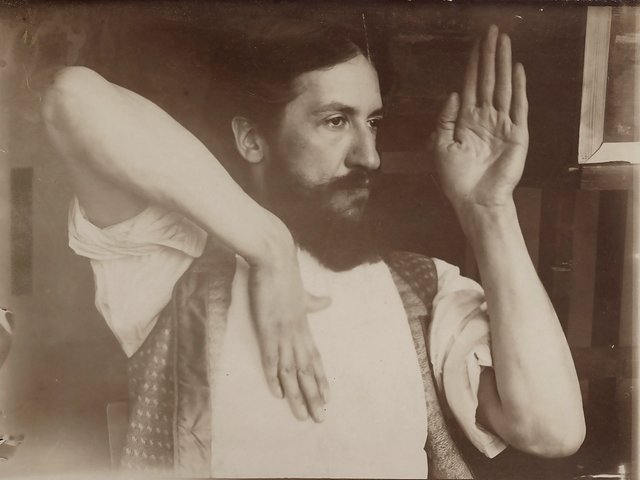

Tosquelles began his professional life treating shell-shocked Spanish Republican soldiers. A member of the POUM, a Catalan Marxist party that stressed local autonomy and about whom the writer George Orwell wrote admiringly, he was seen as a heretical enemy by Spanish communists. The young psychiatrist fled on foot to France and was then detained at a prison camp in Septfonds. From there, he was recruited to work at the asylum-village in a former castle in Saint-Alban.

Under this doctor, the then filthy asylum, filled with “patients” fleeing the Nazis, became a haven for institutional therapy, an approach that involved levelling hierarchies between doctors, staff and patients—a revolutionary departure from France’s penal approach to mental health at that time. This meant that patients were permitted and encouraged to work on local farms, where food, crucial during wartime, was provided. Patients also made objects from found items, creating works that juxtaposed materials in odd ways that charmed visiting Surrealists. The poet Paul Éluard, who hid at the remote Saint-Alban asylum along with his wife and son, was joined by Tristan Tzara and other “real” artists. The patients were also permitted to barter their creations, which Tosquelles encouraged: “I was extremely touched by the sympathy that came out of this experience, this quest, this constant demand for humanity that I found among them,” Tzara is quoted as saying.

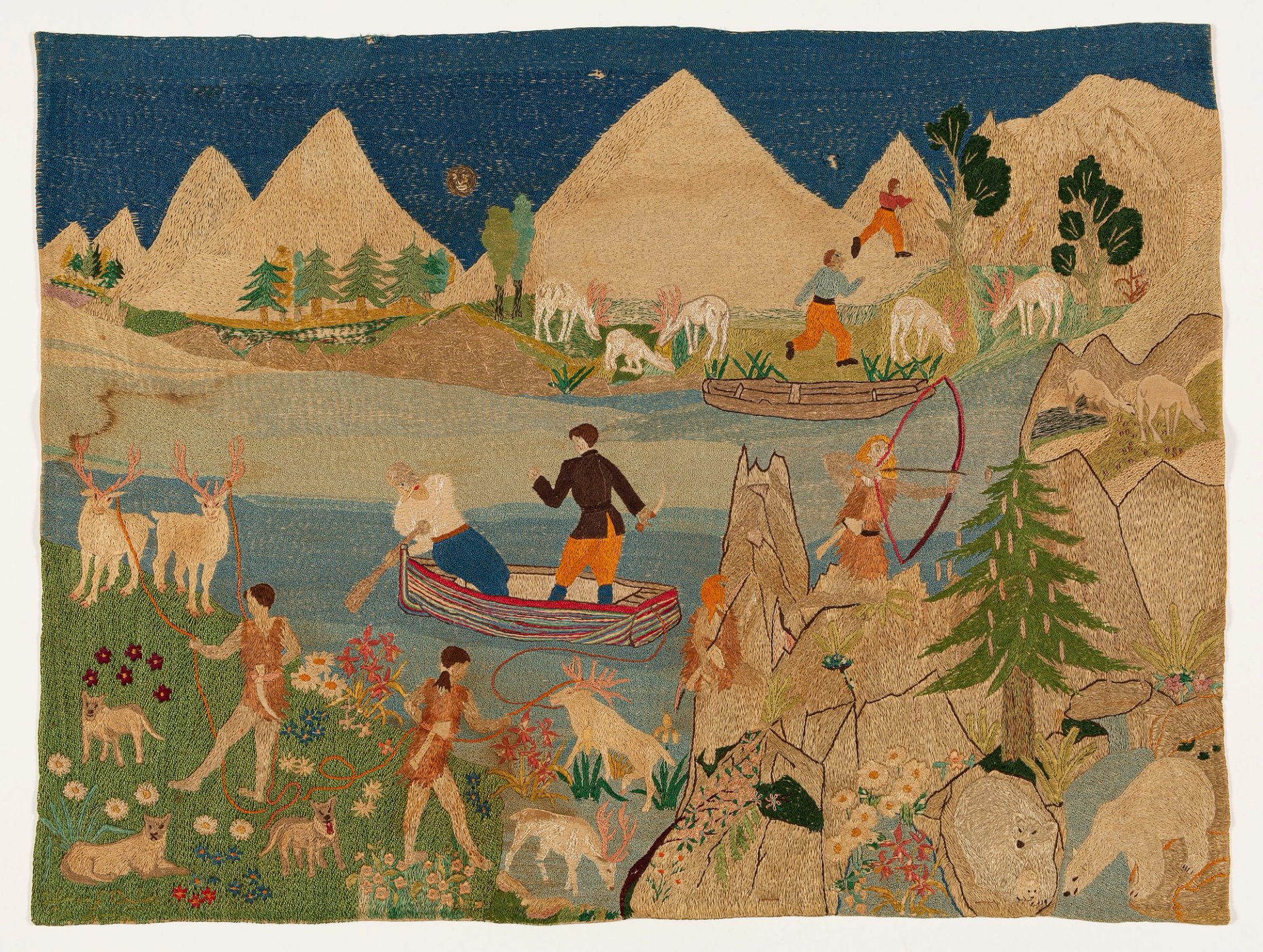

Marguerite Sirvins’s Landscape with Boats, Hunters, and Animals (around 1944–55) Courtesy of Lille Métropole Musée d’art Moderne, d’Art Contemporain et d’Art Brut

Despite the constant threat of starvation, life at Saint-Alban was enviable, given the brutal Nazi pursuit of Jews and other enemies. The book’s format—an exhibition catalogue with essays of varying lengths—never gives a clear reason why Saint-Alban still functioned throughout the war. Perhaps the Nazis and their French collaborators thought that a few psychiatrists and their patients, starved into silence elsewhere, were not worth the trouble. Another advantage was that Tosquelles spoke French with a Catalan accent so heavy and filled with invented terms that even his associates struggled to understand him. (Readers can hear for themselves in the documentary film Une Politique de la Folie by François Pain, 1989.)

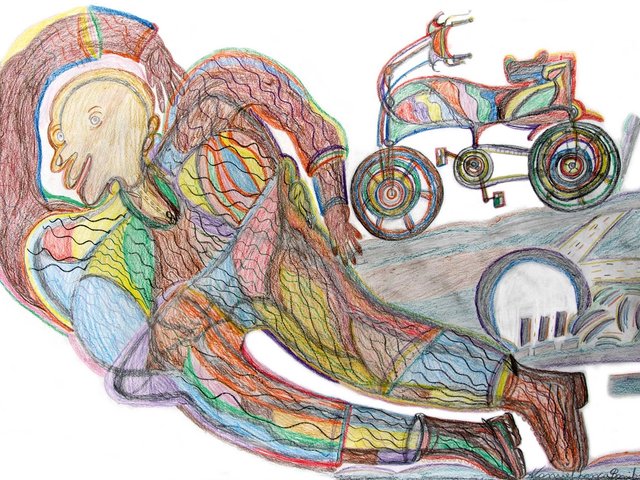

In 1945, Jean Dubuffet visited Saint-Alban, finding examples of an un-instructed and (at that point) un-monetised “art brut” among the patients. By this term Dubuffet meant “works of art emanating from obscure personalities, maniacs, arising from spontaneous impulses, animated by fantasy, even delirium”. Foremost among those works were sculptures—carvings and assemblages—by Auguste Forestier (1887-1958), who arrived at the asylum at the age of 14 and remained. Patients such as Marguerite Sirvins (1890–1957) also made embroidery and entire decorated garments from found fabrics. Work that was nothing less than degenerate by Nazi standards was here nourished and preserved.

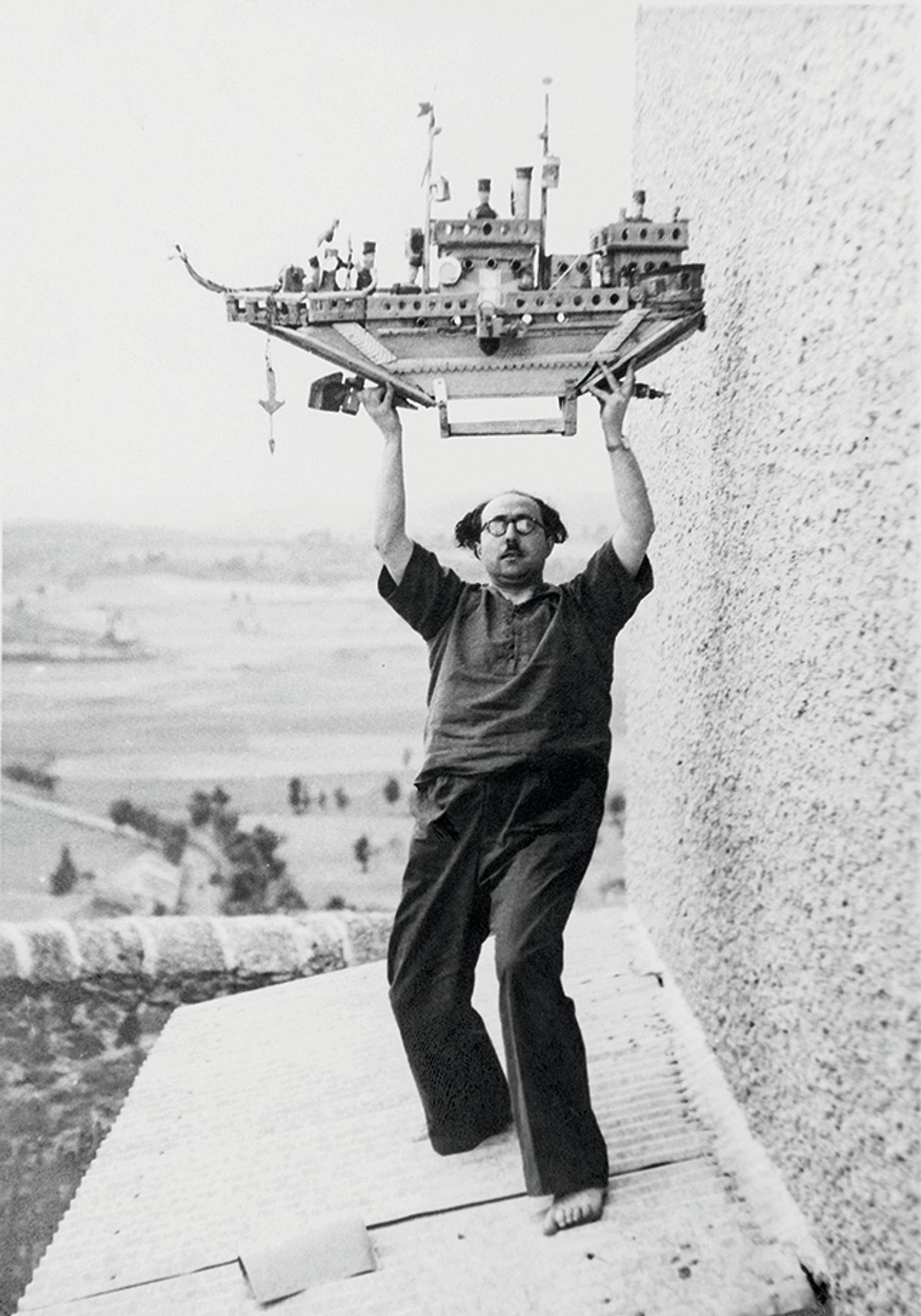

The most celebrated photograph of Tosquelles—on the cover of this book of tributes from a new generation—shows the doctor standing barefoot on the roof of the asylum and holding Forestier’s large, delicate sculpture of a boat in the air: keeping the vessel/asylum afloat?

No manifesto

Dubuffet and Tosquelles would disagree on whether and how objects made by asylum patients should enter the art market and museum collections, yet Saint-Alban and its director impressed the artist with works that needed no manifesto—or just Dubuffet’s approval. Forestier would eventually be collected by other artists, who learned about him through Dubuffet, whom Tosquelles had other reasons to distrust: Dubuffet was suspected of being pro-Nazi and was later quoted making antisemitic remarks (which this volume does not discuss).

In an informative essay, Kaira M. Cabanas notes that “sometime after meeting Dubuffet, Tosquelles observed, ‘When I arrived at Saint-Alban in 1940, Forestier had already invented art brut.’” But what ultimately mattered for Tosquelles was less how Forestier’s work anticipated Dubuffet’s definition of art brut than the specificity of the asylum context—Saint-Alban—in which such creative work was produced. Practising what Tosquelles theorised as co-vivance, the hospital staff lived with Forestier and let him go about his business as he collected his materials. Tosquelles described Forestier’s materials as the “crumbs to make the undergrowth of his own history”.

This anthology will introduce an eccentrically humane figure to readers in English, although a study lighter in jargon could have helped ease that introduction along.

• Joana Masó, Carles Guerra, Valérie Rousseau, Edward Dioguardi and Margarita Sánchez Urdaneta (eds), Francesc Tosquelles: Avant-Garde Psychiatry, Radical Politics and Art, American Folk Art Museum, 356pp, 128 col & b/w illust., $45 (pb), published 1 December 2024

• David D’Arcy is an art critic, journalist and regular contributor to The Art Newspaper