Across the United States, non-profit cultural organisations are grappling with the fallout of a sweeping and abrupt shift in federal arts policy. In April, the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) began rescinding already-approved grants, upending programming plans for hundreds of institutions across the country. Then came the even grimmer news: US President Donald Trump’s proposed federal budget for 2026 would seek to eliminate the NEA altogether, as well as the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) and the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS), both of which also funnel federal funds to cultural organisations in every state.

While the impacts of these cuts are being felt nationally, their most acute effects will be felt by local organisations in places like Miami, where the disappearance of NEA support is the latest in a series of blows to cultural organisations’ budgets. In October 2024, Florida Governor Ron DeSantis vetoed all arts and culture funding in the state’s 2024-25 fiscal year—a $32m cut that shocked even seasoned culture workers and advocates. Recently, Miami-Dade County’s Department of Cultural Affairs has quietly been advising arts leaders that they are expecting a significant reduction in grant-making due to shifting priorities. Together, these lost sources of support amount to a perfect storm for South Florida’s independent and community-based arts organisations, which have helped fuel the region’s explosive growth.

“For us, it’s a triple threat,” says Naomi Fisher, the co-founder of the artist-run non-profit Bas Fisher Invitational (BFI). “Federal, state and local support—many programmes are disappearing at once. It’s not just a budget cut. It’s existential.”

Organisations like BFI, Edge Zones and the Diaspora Vibe Cultural Arts Incubator (DVCAI) are not just art spaces—they are scaffolding. They offer what commercial galleries, market-driven institutions and biennial exhibitions cannot: consistent, values-driven support for artists at pivotal moments in their careers. These are places where young creators’ first exhibitions happen, where underrepresented artists find long-term advocates, where community dialogue is not a tagline but a mission.

With a small staff and limited budget, Edge Zones presents monthly events while sustaining year-round opportunities through workshops, festivals, international exchanges, residencies, publishing and mentorship. “Our mission is rooted in connection, access and artistic practice, and we are proud to have supported the early and ongoing careers of many artists in the region,” says Gabriela Keddell, the organisation’s creative director, administrator, event coordinator and curator. “Last year, we experienced a significant reduction to our operating budget following the state of Florida’s decision to suspend general operating support for arts organisations.”

Keddell adds: “These funds are crucial—they keep our lights on, support our staff and help maintain the infrastructure necessary to serve our community. As of now, it remains unclear whether that funding will be restored this year, and the uncertainty places additional strain on already limited resources.”

“We’re not just losing grants—we’re losing lifelines,” says Rosie Gordon-Wallace, the founder and curator of DVCAI. The organisation, which received a three-year ArtsHere grant through South Arts, funded by the NEA and the Wallace Foundation, was told in May that the funding would be terminated immediately. “As of 31 May, if you have not spent the dollars assigned for this first year, those dollars will be recalled,” Gordon-Wallace recalls being told. “The anxiety on that Zoom call...it may as well have been in person.”

That grant DVCAI had received was worth $98,000 over three years, which was meant to support “Welcome to Miami”, a programming initiative based in the space’s new venue at Barry University. Now, exhibitions will be fewer and stretch longer. “We’ll continue to work with artists,” Gordon-Wallace says. “But it is the scale that will change.”

According to the “Arts & Economic Prosperity 6” study by Americans for the Arts, the non-profit arts and culture sector in Miami-Dade County generates an annual economic impact of $2.1bn. Of that, $1.2bn stems from organisational spending and $856.1m from audience-related expenditures—21.4% of which comes from non-local attendees, underscoring the role of the arts in driving tourism in South Florida.

Cuts at every level

Despite the economic impact of the arts in Miami, state and county grants contribute just a fraction of the dollars that arts organisations deliver for tax and tourism revenues. In its 2025-26 budget—which has been approved by the legislature and now awaits DeSantis’s signature—the state of Florida has allocated around $39m for arts and culture, though those funds would go to far fewer organisations than in years past. DeSantis has also vowed to veto “at least” $500m from the overall $115bn state budget, so arts funding may once again be abruptly reduced or cut entirely once the governor has had his say.

Meanwhile the Miami-Dade County Department of Cultural Affairs’ budget for fiscal year 2024-25 was slashed from $25.5m to $23.1m, a reduction linked to falling Tourist Development Tax revenues. The county did restore $1.5m and secured $400,000 from a private donation campaign, but a shortfall remained and consequently reduced the grants awarded to local arts organisations. Recently, leaders at the Miami-Dade County Department of Cultural Affairs called a meeting with local arts leaders to warn them that funding for fiscal year 2025-26 would, “save for a miracle”, be drastically reduced. (Representatives for the Department of Cultural Affairs did not respond to a request for comment.)

These funding gaps are reverberating across the city. The co-founder of BFI, Naomi Fisher, says the organisation has already had to cancel programmes. “We were supposed to get $40,000 from the state. Then it was cut to around $17,000. Eventually, it was vetoed altogether,” she says. An artist-led project the organisation was planning also lost $13,000 in funding. “We had to completely cancel our fall programming,” she says. “We're now pouring everything into the spring.”

Frances Trombly and Leyden Rodriguez-Casanova, artists and the co-directors of the alternative art space Dimensions Variable, are facing similar challenges. “We lost $25,000 in state funding,” Trombly says. “And there’s a high chance our county support will be significantly reduced.”

After a period of financial relief post-pandemic, Trombly and Rodriguez-Casanova have watched grant sources dry up. “We were kind of okay,” Rodriguez-Casanova says. “But by 2023, we saw everything start to go down.” He adds: “We had to pivot. We’d been subsidising artists’ studios at incredibly low rents, thinking we were building a sustainable ecosystem—but it just wasn’t working.”

Dimensions Variable’s NEA grant—$20,000 over two years—was to be used to commission essays from writers and artists for an online journal, providing essential criticism of their residents’ work. But now, even that modest support has been rescinded. “That was our first time applying, and we got it. But it’s gone,” Trombly says. With skyrocketing rent and fewer philanthropic lifelines, they are recalibrating by charging higher rents and creating an artist membership programme that thus far has 28 members.

‘We’re being used’

The slashes to cultural funding are in stark contrast with Miami’s hard-won position as a global art capital—particularly during the annual Art Basel Miami Beach fair every December. “People love to come to Miami for Basel,” says Gordon-Wallace. “But the infrastructure to sustain local artists is not there.” She notes that while museums and galleries might bring in international stars, local artists struggle for visibility. “Our museums are just as desperate. To get attention, they have to bring in Ai Weiwei.”

The same non-profit sector that supports more than 31,000 jobs and welcomes more than 16 million attendees annually is struggling to stay afloat. “We’re being used for our glitz and our glam and our weather,” Fisher says. “But not enough of the things that an arts ecosystem needs to survive are here.”

Beyond budget concerns, the cuts’ consequences are also deeply personal. “When the NEA shuts down, it’s not a building that closes,” says Gordon-Wallace. “It’s human lives.” She has had to contemplate pay cuts for staff, some of whom are starting families. “If you’re earning $60,000 this year, maybe we have to bring it down to $30,000 next year.”

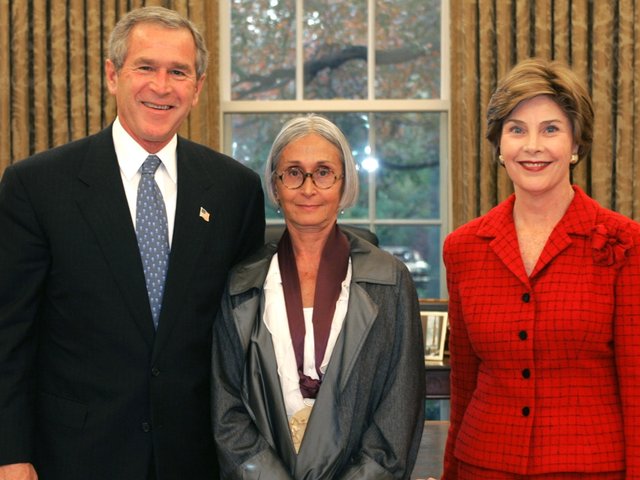

Jen Stark’s Sundial Spectrum (2024) at Elevate Española during last year's Art Basel Miami Beach fair Photo: Peter Vahan

For the leaders of local arts organisations in Miami, the mission is not just about keeping the doors open for the public, it is also about supporting artists. “BFI has supported so many firsts,” says Fisher. “We helped Jamilah Sabur with her first proscenium stage performance, excerpts from it were included in her show at the Hammer Museum. We supported Jen Stark’s first solo show. These artists didn’t just come out of nowhere—they came from community.”

Gordon-Wallace concurs, adding that the city’s cultural organisations “change lives. We take creative ideas and help turn them into something sustainable. And we do it not with abundance, but with belief.”

Despite the urgency of the moment, hope flickers. “I’m old,” Gordon-Wallace says with a laugh. “But I still believe.” She is postponing her retirement to help DVCAI navigate this crisis and plans to make a direct appeal to local business leaders. “We’re going to need to find new allies—people in our own community who haven’t given yet. We need to build something we’ve never had before: a real infrastructure.”

The current funding crisis is the latest in a series of challenges faced by Miami-based cultural producers, who have faced astronomical rent increases and organisational turmoil in recent years. The loss of organisations like these would decimate yet another support system for artists who need it most—and heighten the risk of a homogenised, market-driven cultural landscape.

“Without organisations like ours, we won't have artists from a range of backgrounds continuing to pursue this path,” Fisher says. “The beauty about art is how we convey the full lived experience of being human, and I think the lack of funding for artist-centred spaces leads to a less robust experience of the world.”