The Indian-born British painter Celia Paul (born 1959), best known for her intensely haunting portraits and self-portraits as well as her atmospheric landscapes and seascapes, trained at the Slade School of Fine Art in London. In 1977, when she was just 18, Paul was introduced to Lucian Freud (1922-2011) when he was at the school as a visiting tutor, and so began a ten-year relationship and the birth of the couple’s son Frank in 1984.

In this sumptuously illustrated and produced book, which covers the length and breadth of Paul’s career, the authors, including Hilton Als, Clare Carlisle, Karl Ove Knausgaard, Edmund de Waal and Rowan Williams, as well as the artist herself, make a compelling case for Paul as a single-minded and singular artist, set apart from the figure often seen in Freud’s shadow and considered only on the fringes of the Colony Room set and School of London painters such as Freud, Francis Bacon (1909-92), Michael Andrews (1928-95) and Frank Auerbach (1931-2024).

The story of a young art student and her much older lover becomes more complex and nuanced than might be imagined in this new account of her life and work. Paul’s white-knuckled determination to succeed, to borrow a term from the novelist Esther Freud, shines through.

Finding her voice

There could not be a better time to publish a book on the life and work of Paul, coming, as it does, almost 50 years since she began her training at the Slade and more than a decade since Freud’s death. Further, it is now a decade since the death of the artist’s mother, followed in 2021 by the death of Paul’s husband Steven Kupfer. Now, in the wake of her recent solo exhibition Colony of Ghosts at Victoria Miro in London, Paul seems to find her voice in this book, a long overdue tribute to one of the most passionate, prolific and dedicated artists in Britain over the past 50 years.

The multitude of images in this book is spectacular. The reader is furnished with more than 500 high-quality colour reproductions presented chronologically and with space to breathe, which gives a strong visual narrative to the publication. They reveal what has, perhaps, always been hiding in plain sight: Paul’s need to find meaning in close relationships, whether with family members or familiar interiors and landscapes. Her repeated attention to her subjects and relationships might be understood as something akin to a child picking a scab, patiently yet determinedly working to reveal what is beneath the surface of things. That said, the images do somewhat dwarf the relatively short essays and interview, although the texts have their own strengths, explored here through several compelling threads that run throughout the book.

Celia Paul’s Room, Great Russell Street, Morning (2020) Courtesy of Victoria Miro

Paul’s mother and sisters are recurring subjects from the beginning. Indeed, as Carlisle (the philosopher and biographer) observes in her essay, “My mother …” is a sentence everyone can utter, whether it continues in the past or present tense. Paul returns to her mother as a sitter time and again; she must paint people who mean something to her and the person who meant most was her mother. (The first works she showed to Freud when they met were of her mother.) Paul painted their relationship over a period of 30 years or so. She charged her mother with raising her son while she dedicated herself to painting—a remarkable exercise in trust. It was only when her mother was no longer able to climb the 80 steps to Paul’s small Bloomsbury studio that she turned to her sister Kate as her main sitter. When her mother died, Paul painted My Sisters in Mourning (2015-16), where the ghostly grey sisters sit sadly and quietly together, with hands clasped on their laps.

Self-portraits are plentiful and crucial. Paul explains that since the deaths of Freud, her mother and her husband Steven, she needed to find a way to redefine herself. It was then she began to paint strangers as a way of being less of a stranger to herself. As she explained in conversation with the artist-potter Edmund de Waal, she also began, prompted by grief, to write two books—Self-Portrait: Celia Paul (2022) and Letters to Gwen John (2024)—when painting did not seem to fill the void.

From the inside, out

Paul paints in silence, explaining that the energy comes from inside not outside. In his essay, the novelist Knausgaard suggests that when looking at the few objects that appear in Paul’s paintings (a chair or a bed, perhaps), more information comes from inside the viewer than outside. A painting of Paul’s showing an empty chair draws the viewer’s gaze to an absent presence. The empathy and power of the paintings is palpable. Their starkness is overwhelming.

Paul wanted to address her role as model, not artist, in these paintings, to free herself from the label of muse

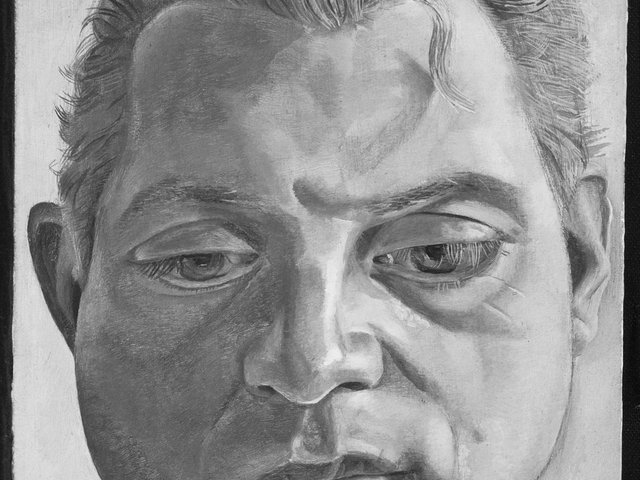

In a riposte to Freud, Paul turns to his paintings of her when she was between the ages of 20 and 27. She never sat for anyone else and wanted to address her role as model, not artist, in these paintings, to free herself from the label of muse. In Freud’s Naked Girl with Egg (1980-81), she recalls feelings of vulnerability, exposure and powerlessness. In response, she paints Ghost of a Girl with an Egg (2022), where the vulnerable flesh takes on more spiritual qualities. In Paul’s Painter and Model (2012)—a powerful yet pithy rejoinder to Freud’s Painter and Model (1986-87)—she dispenses with the male model altogether and paints herself as painter, anguished, bare-footed, spattered and surrounded by discarded empty tubes of paint. It conveys something of how difficult she finds her chosen path.

The theologian Williams raises some fascinating ideas in his essay and focuses on Paul’s ten paintings made while on residency in Venice in 2023. Williams recognises the longstanding themes of Paul’s painterly concerns in these works (mothering, generating, recognising, losing), but suggests she approaches them in new and important ways. The addition of a distinctive green/turquoise palette, the reworking of traditional compositions—such as Giorgione’s The Tempest (1506-08), for instance—and the representation of liquid surfaces in these painting, he suggests, are some of Paul’s greatest innovations and represent the culmination of her work of the previous decade.

The Colony

One cannot conclude without saying something about Paul’s Colony of Ghosts (2023). The Colony Room was a popular Soho drinking haunt founded by Muriel Belcher in 1948 and frequented by Freud, Bacon, Andrews and others. Paul’s painting takes precisely the same dimensions as Andrews’s painting The Colony Room I (1963). It also takes its cue from John Deakin’s well-known photograph of “School of London” painters together at Wheeler’s restaurant, from 1963, but focuses the viewer’s gaze, and her own, more tightly.

Across the 50 years covered in this publication, Paul insists that she is the same person she has always been: “I can stretch out my old hand—with its age spots—and hold my young unblemished hand”. Yet, she seems bolder and braver than ever before. No longer in Freud’s shadow and having well and truly exorcised the Colony Room ghosts, Paul, it seems, is finally receiving the recognition she deserves.

• Celia Paul: Works 1975–2025. By Celia Paul, with contributions by Hilton Als, Clare Carlisle, Katy Hessel, Karl Ove Knausgaard, Edmund de Waal and Rowan Williams. Published 1 February by MACK, 544pp, colour illustrations throughout, €175/£150/$190 (hb)