The use of sacred clan designs as tools of soft power in the battle for sea and land rights is being explored in a Sydney exhibition of Yolŋu art from Australia’s Northern Territory.

Yolŋu power: the art of Yirrkala at the Art Gallery of New South Wales (AGNSW) features the work of 90 artists made in the past eight decades. It foregrounds the small coastal community of Yirrkala—inhabited primarily by Yolŋu people—and its art centre Buku-Larrŋgay Mulka, which was established in the 1970s.

At the opening, AGNSW director Maud Page described Yirrkala as “Australia’s most internationally acclaimed art community”. (An exhibition titled Maḏayin, a collaboration between Kluge-Ruhe Aboriginal Art Collection and Indigenous knowledge holders from the Buku-Larrŋgay Mulka Centre in Yirrkala, has been touring across the US.)

AGNSW’s head of First Nations, Cara Pinchbeck, meanwhile, explained how the power of Yolŋu culture was embedded in sacred patterns and designs called miny’tji. These designs are manifestations of a person's connection to the land, and have been handed down and reinforced across many millennia.

With the arrival of missionaries in the Northern Territory in the 1930s, and bauxite mining companies and commercial fishing in the decades that followed, Yolŋu people were forced to fight for their land, their sea and their way of life. They did so through art, says the Yolŋu artist—and Madarrpa clan leader—Djambawa Marawili.

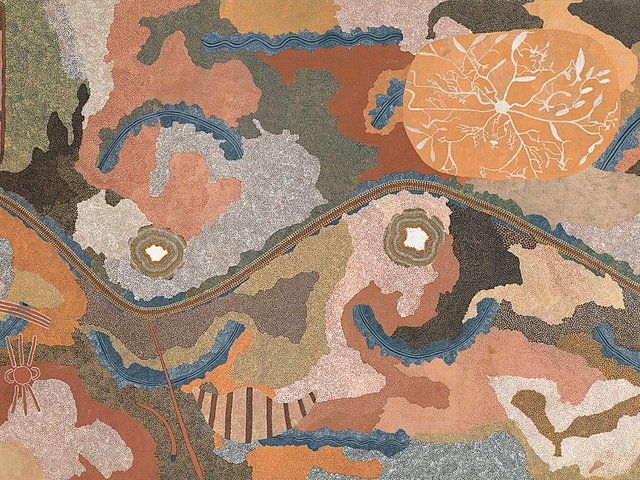

Installation view of Yolŋu power: the art of Yirrkala

All artworks © the artists, Buku-Larrŋgay Mulka Centre, Yirrkala, photo © Art Gallery of New South Wales, Diana Panuccio

Depictions of sacred miny’tji now took on a new role, with Yolŋu presenting them to Australia’s federal parliament and High Court as documents to prove continuous and unbroken connection to place.

“When we needed strength to fight against political attacks, all we could do was paint these patterns and say, ‘This is our pattern, this is our story, this is our document.’ We never wrote it in a book; we showed it through the patterns and designs. In our paintings, we show that we own these places,” Marawili stated in the Yolŋu power exhibition catalogue.

In 1963 the famous Yirrkala Bark Petition became the first document prepared by Indigenous Australians to be formally recognised by parliament.

Written in English and a Yolŋu language called Gupapuyŋu, the Bark Petition (or Ṉäku Dhäruk) protested the removal without consultation of Yolŋu land for mining. Copies of the typed statement were glued to bark and surrounded by painted renditions of various sacred clan designs.

With the passing of the Land Rights Act in 1976, Yolŋu were recognised as the rightful owners of their ancestral lands. But the fight for rights continued.

A breakthrough with bark

The variety with which miny’tji was used to declare Yolŋu rights is made clear in the exhibition. In 1996, a poacher fishing on Blue Mud Bay near Yirrkala shot and beheaded a crocodile, a sacred creature known as baru. Outraged by the insult to his own personal totem, Marawili initiated the Saltwater Project, in which 47 Yolŋu artists produced bark paintings that claimed rightful ownership of sea country. Several works from this series are on display in Sydney.

The Saltwater Project had a profound legacy. In 2008, the High Court of Australia ruled in favour of Yolŋu in the Blue Mud Bay case. Indigenous ownership of the intertidal zone was recognised for the first time under the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act of 1976.

Noŋgirrŋa Marawili, Garraŋali (1998)

© Estate of Noŋgirrŋa Marawili, Buku-Larrŋgay Mulka Centre, Yirrkala

The Yolŋu power exhibition features a more recent assertion of identity too: 22 new “rumbal” paintings on bark that detail the sacred designs of the 16 clans.

A sharing of stories

Numerous Yolŋu artists and community members from Yirrkala and surrounding homelands travelled 4000 km to Sydney for the opening weekend talks and workshops. The opening night featured a special performance by Yolŋu dancers led by Marawili.

Senior Yolŋu elder and artist Djambawa Marawili at the opening of Yolŋu power: the art of Yirrkala

Photo: Art Gallery of New South Wales, Joshua Morris

In a public talk on the first weekend, Marawili along with fellow Yolŋu artists Yinimala Gumana and Wirrandan Marawili outlined some humorous incidents in their people’s long fight for land and sea rights.

Prior to sea rights being granted to Yolŋu, Marawili grew annoyed by what he felt were indiscriminate commercial fishing practices on Blue Mud Bay.

One day, he attached one end of a commercial fisherman’s net to his troopy (troop carrier) and pulled hard while the fisherman at the other end pulled back just as hard.

Unbeknown to Marawili, the fisherman was Senator Nigel Scullion, who would go on to be the minister for Indigenous affairs in Tony Abbott’s conservative government.

The next day the pair were discussing land rights in Canberra, Marawili said, when they recognised each other from the tussle. “I said, ‘what are you doing here?’. He said, ‘what are you doing here?’.” As for the tug of war on Blue Mud Bay, “I beat that fella”, Marawili said.

- Yolŋu power: the art of Yirrkala, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, until 6 October