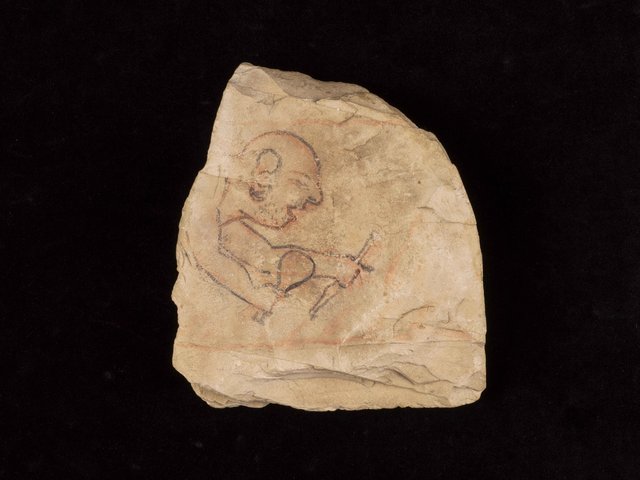

An Ancient Egyptian handprint dating back around 4,000 years has been found on an artefact at the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, UK. Researchers working on the museum’s forthcoming show Made in Ancient Egypt (3 October-12 April 2026) made the discovery on the base of a “soul house”—a model of a building rendered in clay.

“Soul houses” date back to Egypt’s First Intermediate Period and Middle Kingdom (around 2055 BC–1650 BC), and are often found at burial sites. It is believed that they were used as places to leave offerings of food—such as bread or an ox’s head—or as sanctuaries for the deceased person’s soul.

Helen Strudwick, the curator of Made in Ancient Egypt and a senior Egyptologist at the Fitzwilliam, explains that “much ink has been poured out on the subject of these buildings—whether they represent the person’s house on earth, or whether it is the tomb. ‘Soul houses’ were placed directly over the burial shaft, which strongly suggests that they were a replacement for fancy tomb chapels [structures built beside burial chambers] for people who couldn’t afford anything like that, although I think there’s also a connection to the idea of the dead being able to return to their homes“.

The Fitzwilliam example—discovered at a site called Deir Rifa, about 280km north of Luxor—features a two-storey structure supported on columns, with staircases running up one side. It was carefully hand-crafted: conservation has revealed how the maker would have used wooden sticks to make a framework and coated it with clay, while creating the staircases by pinching the material while it was still wet. The object would then have been fired, burning the wooden structure away.

A front view of the Fitzwilliam Museum’s “soul house”

Courtesy of Fitzwilliam Museum

The handprint was likely made when the “soul house” was moved outside to dry. It was found, Strudwick says, when Fitzwilliam conservators examined the structure under different lighting conditions.

“People often don’t look at the undersides of objects, so the handprint was not something we had ever noticed until it was pointed out by our most senior conservator Julie Dawson (who co-curated with me the Fitzwilliam’s previous Egyptian exhibition in 2016).”

The discovery is significant within the study of Ancient Egypt, Strudwick adds in a statement. “We've spotted traces of fingerprints left in wet varnish or on a coffin in the decoration, but it is rare and exciting to find a complete handprint underneath this soul house,“ she says. “This was left by the maker who touched it before the clay dried.

“I have never seen such a complete handprint on an Egyptian object before. You can just imagine the person who made this, picking it up to move it out of the workshop to dry before firing.”

She continues: “It would be interesting to see whether other soul houses have handprints under them too. We have another ‘soul house’ from the same site in our collection—we will be taking a look soon.”

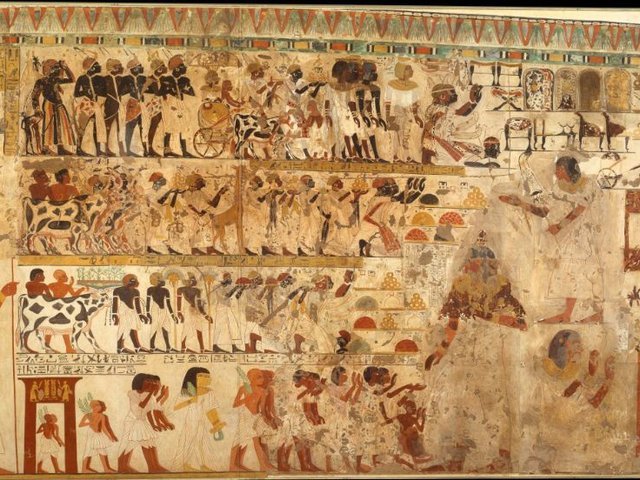

Artisans were crucial members of Ancient Egyptian society, decorating the tombs and creating the objects that have engendered such a deep fascination for this period of history across the world. Excavations at important sites such as Deir el-Medina—a workers' town in Luxor, near the famous Valley of the Kings—have offered rich insight into the way in which craftspeople worked, lived and conversed. In 2021, meanwhile, a mud-brick complex known as the area’s “lost golden city” was unearthed, filled with tools, urns and other items relating to daily life.

The Made in Ancient Egypt exhibition intends to shed fresh light on these artisans and their achievements, bringing together objects ranging from Ostraca—small pieces of ceramic or stone used to document various, sometimes humorous everyday exchanges—to intricately decorated mummy cases and glassware.