A marble bust dating from the first century CE in the early days of the ancient Roman Empire, and believed to have been stolen from an Italian museum at some point in the last century, was turned over to the Italian government in a ceremony on 5 August. The move ends a seven-year legal odyssey that began in early 2018 when the sculpture was seized by the Manhattan District Attorney’s Antiquities Trafficking Unit from Safani Gallery, a Manhattan-based antiquities gallery.

“The DA’s office had been notified of the stolen bust by law enforcement in Italy, probably the Carabinieri, which has its own art and antiquities crime unit, because someone in Italy had seen that this gallery in New York had it,” says Leila Amineddoleh, a partner in the Manhattan law firm Tarter Krinsky & Drogin, who became involved in one of the lawsuits filed by the gallery, which sought to be compensated by the Italian government for the seizure of the bust.

In many ways, this incident is a by-the-books case of stolen or looted property from abroad that finds its way to New York City, where so much of the cultural property trade takes place. The bust, identified in court papers as the “Head of Alexander”, was excavated in the early 1900s by Italian archaeologists along the Via Sacra, a main thoroughfare linking the Capitoline Hill to the Colosseum in central Rome. The bust was handed over to a local museum that was eventually taken over by the Capitoline Museum in Rome, although at some point the sculpture was listed as “missing”. (“By ‘missing’, it really means stolen,” Amineddoleh says.)

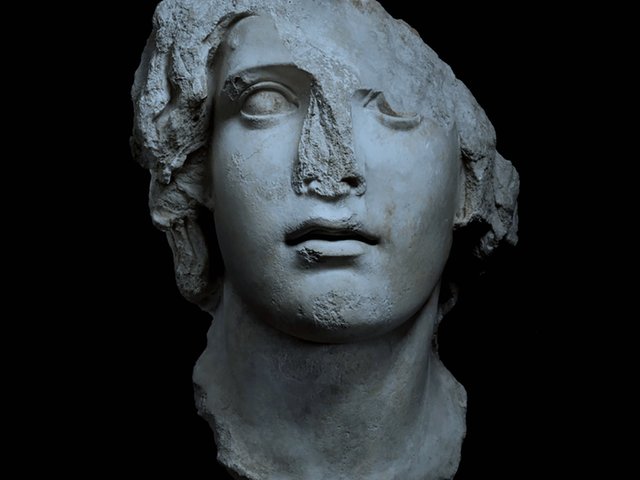

The bust is not in pristine condition, with a portion of the top of the figure’s head and its nose missing. “The head is valuable,” Amineddoleh says, “but not in the millions of dollars, maybe in the hundreds of thousands of dollars.” She also does not believe that the bust is of Alexander the Great, but “Head of Alexander” is the name that has been assigned to it.

After the bust went missing, it travelled from Rome to New York City, Cairo, London and then back to New York, selling in 1974 for $650 at what was then called Sotheby Park Bernet and at a later time for $92,500 at auction, before it was finally purchased at auction for $150,000 by Safani Gallery in 2017. But, once the object was identified (thanks to an advertisement run by the Safani Gallery for a 2018 art fair), it was claimed by the Italian government under a 1909 law, the Code of the Cultural and Landscape Heritage, which claims state ownership for all archaeological objects discovered after 1909 unless the Ministry of Culture acknowledges that the object does not have any cultural interest.

The ancient marble bust alongside other objects being returned to Italian authorities in a repatriation ceremony in Manhattan on 5 August Courtesy Leila Amineddoleh

Prolonging the process of returning the bust to the Italian government were a series of lawsuits brought by Safani Gallery, first against the Italian government (Amineddoleh was hired by that government to represent it in a New York district court) and later against the Italian Ministry of Culture, claiming an “unlawful taking” and demanding compensation for its loss. Those claims were dismissed, as was another claim that the Manhattan District Attorney’s office had been acting as an arm of the Italian government. Getting all the legal matters resolved took seven years. During the ceremony on 5 August, held at the Manhattan Criminal Courthouse, the “Head of Alexander” and 30 other artefacts were handed over to representatives of the Carabinieri Cultural Heritage Protection Command and the Italian consulate in New York.

Representatives for the Manhattan District Attorney’s Antiquities Trafficking Unit did not respond to The Art Newspaper’s request for comment.

Safani Gallery was represented by David Schoen, a lawyer specialising in federal criminal defence and civil rights law, who was one of the lawyers representing US President Donald Trump during his second impeachment trial in the United States Senate in 2021. Schoen could not be reached for comment as of press time.

There is speculation within the heritage sector that the series of lawsuits reflected a general frustration with the Manhattan District Attorney’s Antiquities Trafficking Unit, which has seized other cultural properties from dealers and museums around the country, claiming New York City has jurisdiction to take possession of these objects awaiting court review.

The Art Institute of Chicago challenged the Antiquities Trafficking Unit when it seized an Egon Schiele work on paper, Russian War Prisoner (1916), which the DA’s office claimed had been stolen by the Nazis from cabaret star Fritz Grunbaum and later laundered through art dealers before arriving in New York; that dispute is ongoing. The Cleveland Museum of Art also had fought in court to stop the DA’s office from seizing an ancient Greek or Roman bronze sculpture of a robed torso that allegedly was looted from Turkey; the parties reached an agreement in February and, following a final special display in Cleveland, the antique bronze was repatriated to Turkey last month.