Art fairs are rightly seen as among the purest distillations of contemporary art commerce today. But many, if not most, fairs also include a subset of exhibitors who complicate that reputation: non-profit organisations. The return of Armory Week in New York offers a timely opportunity to unpack how charitable entities fit into the fair construct in general, as well as tease out the strategic differences in how specific events incorporate them into their programmes.

The 2025 edition of The Armory Show will feature nine non-profit entities amid its more than 230 exhibitors. Eight of those non-profits will be clustered together in a special sector. The ninth, Souls Grown Deep, was invited to build on its mission of championing Black artists from the American South by staging a curated presentation in the fair’s Platform sector for large-scale and site-specific works.

Kyla McMillan, the director of The Armory Show, says that Souls Grown Deep’s position “will push to the fore that fairs are about artists at their core. Whether in conversation with not-for-profits or galleries, the goal is to amplify and support the artist, to create a network around their work.”

Artists are finding community with [not-for-profits], so if we are to be the foundational fair we aim to be, then it feels essential for not-for-profits to be a part of what we doKyla McMillan, director, The Armory Show

The creative tension in this exchange speaks to a larger truth about the pipeline between charitable entities and the market. Non-profit organisations are “often the first level of support for artists before they get gallery representation”, McMillan says, adding: “Artists are using their services and finding community with these organisations, so if we are to be the foundational fair we aim to be, then it feels essential for not-for-profits to be a part of what we do.”

Like most other fairs, The Armory Show holds an open call for applications from for-profit dealers. All non-profit exhibitors, however, must be invited to apply for stands (though McMillan says these invitations “sometimes” come after the fair receives “outreach from not-for-profits having an anniversary year or other milestone”).

What about the costs of participating? The Armory Show awards one New York-based non-profit exhibitor per year its Spotlight prize, which comes with a fully funded stand. (This year’s winner is the Manhattan-based Storefront for Art and Architecture.) The others are offered their spaces at what McMillan calls “a significantly subsidised rate”, along with the ability to invite their donors as VIPs.

When it comes to determining the content of their stands, the fair typically gives non-profit exhibitors “a bit of carte blanche”, McMillan says. Still, she and her colleagues happily offer guidance if asked. “A lot of times they do come to us for our insights, because this isn’t necessarily the environment they’re most active in or comfortable with. In many cases it’s their first fair,” she adds.

The contours of these arrangements often echo the ones used by Frieze, The Armory Show’s parent company, at its own fairs in New York and Los Angeles. Christine Messineo, Frieze’s fair director in the Americas, says the company invites non-profit partners to each event based on “what feels current for the moment and which organisations feel reflective of the moment”. Frieze also typically donates the space each entity uses on-site, providing a golden opportunity to fundraise through sales of editions or other means.

Yet temporary real estate is not always the main currency in Frieze’s work with non-profit organisations. Other initiatives have included co-commissioning performance works with High Line Art during Frieze New York and with the Art Production Fund during Frieze Los Angeles; collaborating with the Black Trustee Alliance to create an audio archive of residents of the Los Angeles County city of Altadena after it was razed by the Eaton fire in early 2025; and partnering with Vote.org to offer voter registration at both of its US fairs.

An Independent approach

Another layer to the interplay between for-profit fairs and non-profit entities emerges at Independent 20th Century, the invitation-only expo dedicated to art from around 1900 until 2000. This year’s edition (4-7 September) brings 31 exhibitors to Casa Cipriani on the southern tip of Manhattan. Although none of the stands will be occupied by non-profits, that outcome stems from the firm’s unusually selective ethos on working with charitable organisations.

“The models are different for big-box franchise fairs,” says Elizabeth Dee, the founder and chief executive of Independent, about her larger competitors’ strategy with non-profit exhibitors. “Because we’re more of a curated project, we’ve tried to think about it a little differently. If we’re working with a non-profit, it’s because there’s a specific project we want to get behind.”

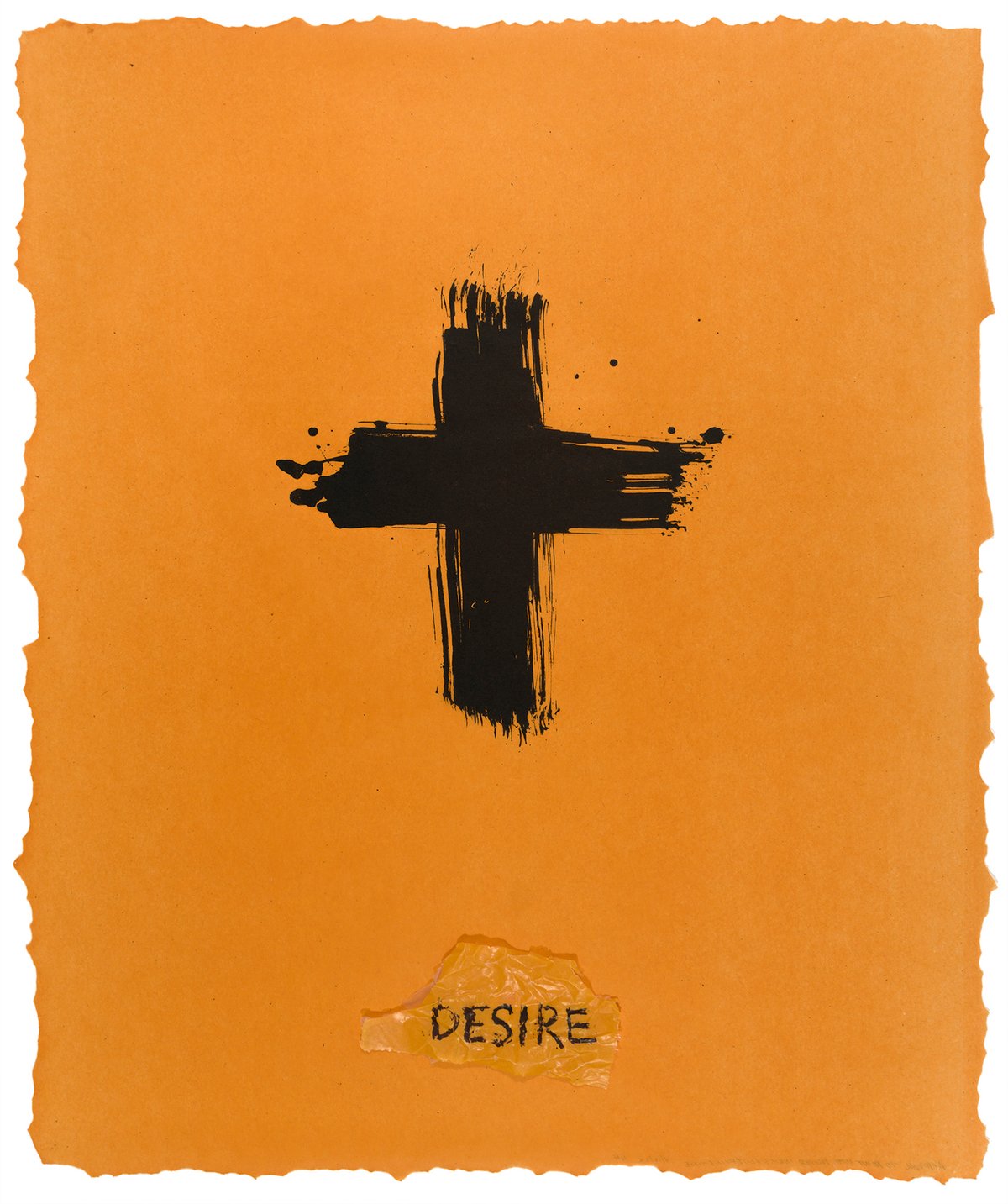

One such example was on view at the 2024 edition of Independent 20th Century: a stand commemorating the 50th anniversary of the Hallwalls Contemporary Art Center, the Buffalo, New York-based non-profit founded by a group of artists including Robert Longo, Cindy Sherman, Nancy Dwyer and Charles Clough.

The presentation comprised a selection of posters, flyers, correspondence and video from the archive co-curated by Independent and Ryan Muller, a director at Sprüth Magers in New York. (The gallery had no involvement in the project.) None of the materials had been exhibited in Manhattan before, and nothing of any kind was for sale—partly because Independent covered the cost of the stand.

“People were surprised to find something that wasn’t for sale,” Muller tells The Art Newspaper of visitors’ reactions to the purely archival display. “It felt like an Easter egg for people who really cared about that kind of history.”

Institutional innovation

Dee and her colleagues have developed other ways to stay engaged with institutional and charitable organisations. In lieu of a standard VIP programme, Independent 20th Century works with the patron groups at a slew of non-profit art institutions, ranging from the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Guggenheim Museum to the Drawing Center and the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture. These partnerships manifest in private members-only programmes at the fair, such as a tour led by Sheena Wagstaff, the Met’s then chairman of Modern and contemporary art, explaining how artists in the museum’s collection were being re-historicised at Independent 20th Century in 2021.

“No one had really asked the museums, ‘What are you looking to do with your patrons? What topics are top of mind with your curatorial team? Are there any overlaps between your collection or exhibition programme and our show?’” Dee says of the fair sector. “We started to really ask those questions and understood there was a way to do this that fairs hadn’t really done before.”

In the end, Independent 20th Century’s institutional alliances show how archaic the old walls separating the industry’s for-profit and non-profit territories have become. The progressive synergies created by art fairs point toward even more ways the two sides could mutually enrich one another going forward—at least, if the traditionalists can learn to stomach the market-driven format.

“Like them or not, they exist,” Muller says of fairs. “People who care about what art is being made are going to go to them. It may be a flawed vessel, but it’s a vessel.”