There is an inherent tension present from the opening pages of Wendy Hitchmough’s new biography, Vanessa Bell: The Life and Art of a Bloomsbury Radical. As Hitchmough explains, Bell (1879-1961) was doing dynamic work as both an artist and a designer in the first half of the 20th century, an era when women making inroads into either world was rare.

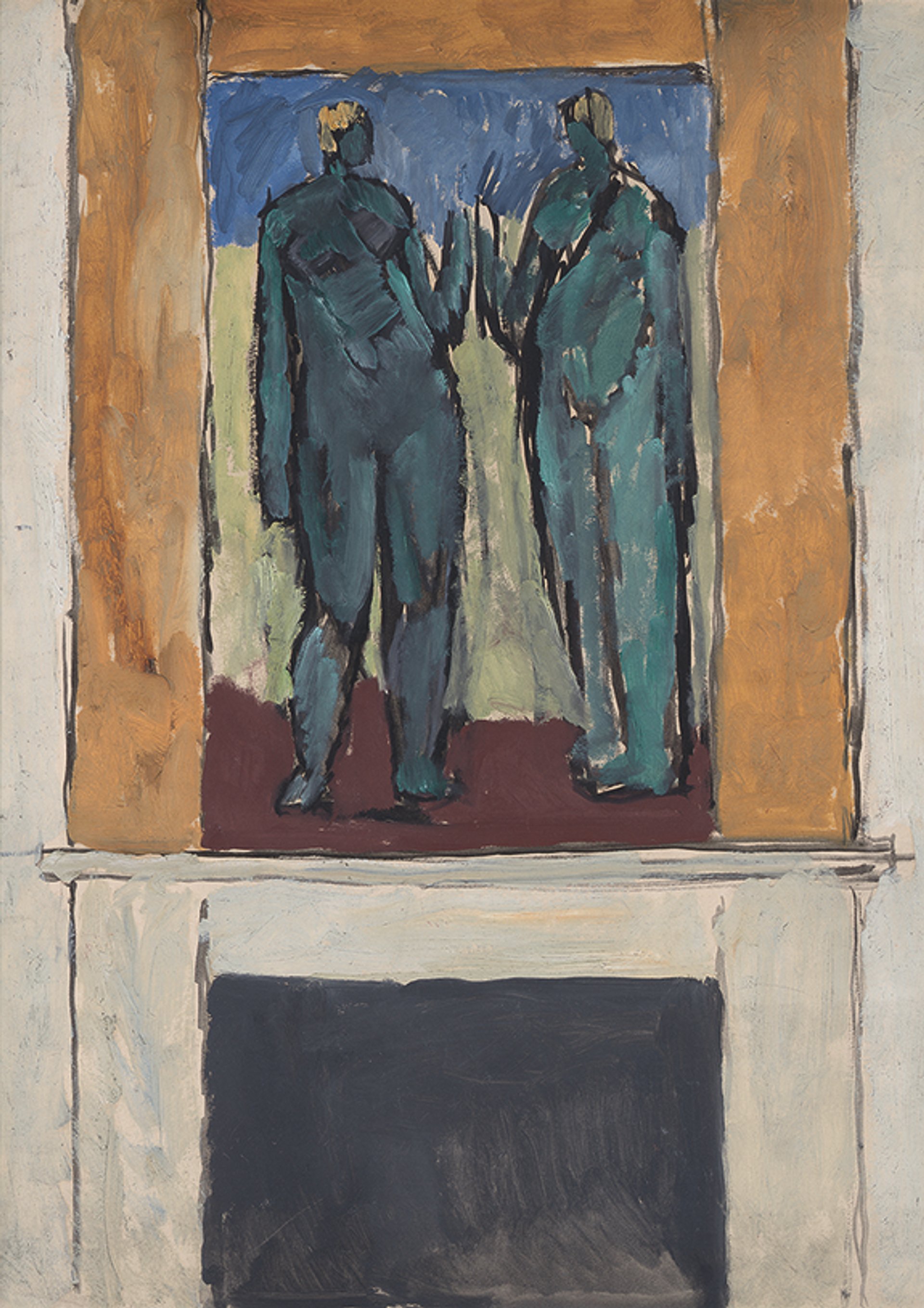

Bell’s Design for Overmantel (around 1912–13), which was intended for her studio in Bloomsbury, London Yale Center for British Art

Hitchmough describes how Bell “subverted and exploited” societal expectations of women of the time, on occasions to bolster her own profile. But there was an alarming counterweight to those efforts: Hitchmough describes Bell as using two distinct approaches to outmanoeuvre the sexism, “collaboration” and “anonymity”. It is from here that the tensions in writing about Bell’s life and work come into focus. As the author notes early in the book, Bell’s 1913 painting Dancing Couple was only attributed to her in 1999.

Similarly, the “life” and “art” of the book’s subtitle exist in a state of tension. In her introduction, Hitchmough asserts that Bell “was central to the evolution of 20th-century visual culture”. It is a compelling and persuasive argument—and Hitchmough, who spent 12 years as the curator of Charleston, the Sussex farmhouse formerly owned by Bell and fellow Bloomsbury Group artist Duncan Grant, knows this milieu in precise detail. But there are also glimpses of the complexities of Bell’s personal and professional encounters; to that end, here is how the book opens: “Vanessa Bell travelled to Paris in March 1914 with one of her husband’s three current lovers, Molly MacCarthy. There they would meet her husband, the art critic Clive Bell, and her lover and business partner, the artist and critic Roger Fry.”

Hitchmough adopts such a matter-of-fact tone throughout. When writing about the interconnected artistic, professional, marital and sexual lives within the Bloomsbury Group, it would be easy to take a more sensationalistic route—or, perhaps, to make explicit the connections between the relative openness of these artists and the expansive sexuality and open relationships of the present moment. But Hitchmough is after something different here; while she has a very clear argument to make—seeking to remind her readers of the importance of Bell’s art and design—she has opted for a methodical approach over a pyrotechnic one.

Bell used two distinct approaches to outmanoeuvre the sexism: ‘collaboration’ and ‘anonymity’

Writing about one Bloomsbury figure often necessitates writing about the larger group, however. One of the most revealing moments in the literature that surrounds them can be found in Bloomsbury Recalled, a 1995 book by Quentin Bell, a writer and art historian who is also—as readers probably know—one of Vanessa’s three children. One late chapter is titled Meetings with Morgan, and it might take a while to realise that the “Morgan” in question is in fact the novelist E.M. Forster. This was the sort of milieu that surrounded Vanessa Bell and her family: a world in which the friends and lovers who casually dropped in are now revered names in the fields of art, literature and design. (Of another visitor, the younger Bell observes: “He turned out to be not the plumber but Lord Gage.”)

Several moments in this biography give a sense of just how much artistic vision came together during Bloomsbury’s heyday. Hitchmough cites the creation of both the Omega Workshops and the Grafton Group as having “applied the aesthetics of Post-Impressionism to the decorative arts”. One of the running themes throughout the book is how Bell found a balance between fine art and more consumerist projects. It is not the only way Bell was ahead of her time, but it is certainly a notable example of it.

Personal tragedies

The final chapter of Hitchmough’s book, titled Late Works and Legacy, is one of the only moments where what went unsaid felt especially impactful. In 1937 Bell’s oldest child, Julian, died in the Spanish Civil War; four years later, her sister Virginia Woolf died by suicide. It is a brutally sad sequence, and two tragedies more than anyone should have to bear. And while Hitchmough’s focus throughout is more on Bell’s artistic and aesthetic work, it is difficult to read a biography like this without wanting to learn more about how Bell reacted to these two personal calamities.

The reproductions of Bell’s art and design work that punctuate this volume tell a story all their own, both in tracing the progression of Bell’s visual style over the course of her life and showing examples of the way that certain motifs and techniques were featured in both. Throughout, Hitchmough is a knowledgeable guide to Bell’s work as an artist and the relationships around her. Hitchmough also provides a welcome context for where Bell stood relative to other artistic movements of the time: “She challenged the urban focus and chauvinism of the Camden Town Group and other modernists.”

From the very beginning of Vanessa Bell, Hitchmough sets herself a challenging task: to enumerate the full scope and influence of Bell’s artistic career. The result is both informative and evocative, a glimpse of a complicated life in one of the most lauded creative milieux of the 20th century. The result is a success; this is a clear and clarifying look at why Vanessa Bell matters.

• Wendy Hitchmough, Vanessa Bell: The Life & Art of a Bloomsbury Radical, Yale University Press, 352pp, 80 colour illustrations, £30 (hb), published 11 March

• Tobias Carroll is the author of five books, including Political Sign (2020) and the novel In the Sight (2024)