Renaissance Skin is the latest publication by Evelyn Welch, the vice chancellor and professor of Renaissance studies at the University of Bristol. The book is the product of a five-year project funded by the Wellcome Institute, which enabled Welch to assemble a team of scholars who contribute to a wide-ranging survey of “skin cultures, animal and human relations, the history of dermatology, the trade in enslaved people, skin markings, paper and parchment technologies, cosmetics and recipe books” in Europe around 1500-1700. Lavishly illustrated throughout, the book’s three parts explore different aspects of pre-modern scientific understanding, as well as individual experiences of skin, whether human, animal or plant in origin. As a methodological approach, Welch adapts art historian Michael Baxandall’s well-known concept of the “period eye” into the “period body”, to “rethink how people in the past understood their own bodies and those of others”. The evidence she discusses comes from diverse written and visual sources, including medical texts, paintings, prints and poetry, as well as employing “experimental history” to better understand contemporary practices, from sausage-making and butchery to the manufacture of parchment and leather.

Part one opens with four chapters on “Skin as Surface” that outline early-modern medical theories. Put simply, in this period skin was viewed as a porous container that held the organs together, composed from “internal vapours” that rose to the surface of the body where they congealed into two layers: the “true skin” below, covered by the outer “scarf skin”. Various substances (“excrements”), such as sweat, hair and tears, escaped through these layers, along with noxious vapours generated by diseases inside the body. These poisonous airs might also cause infection by passing in through the skin’s pores. Physicians relied on antique theories, using the Galenic system to identify and correct imbalances in the four bodily humours—blood, phlegm, black bile and yellow bile—which affected the temperament and, hence, the health of the patient. Welch notes that the appearance of the skin was important in diagnostic practices, such as physiognomy, where it was used to assess both internal health and moral character. She also examines medical, civic and artistic responses to smallpox, “French pox” (syphilis) and leprosy, and charts advances in scientific knowledge, initially centred in Padua, where new theories proposed that maintaining “beautiful” unblemished skin was vital to health, rather than a vanity.

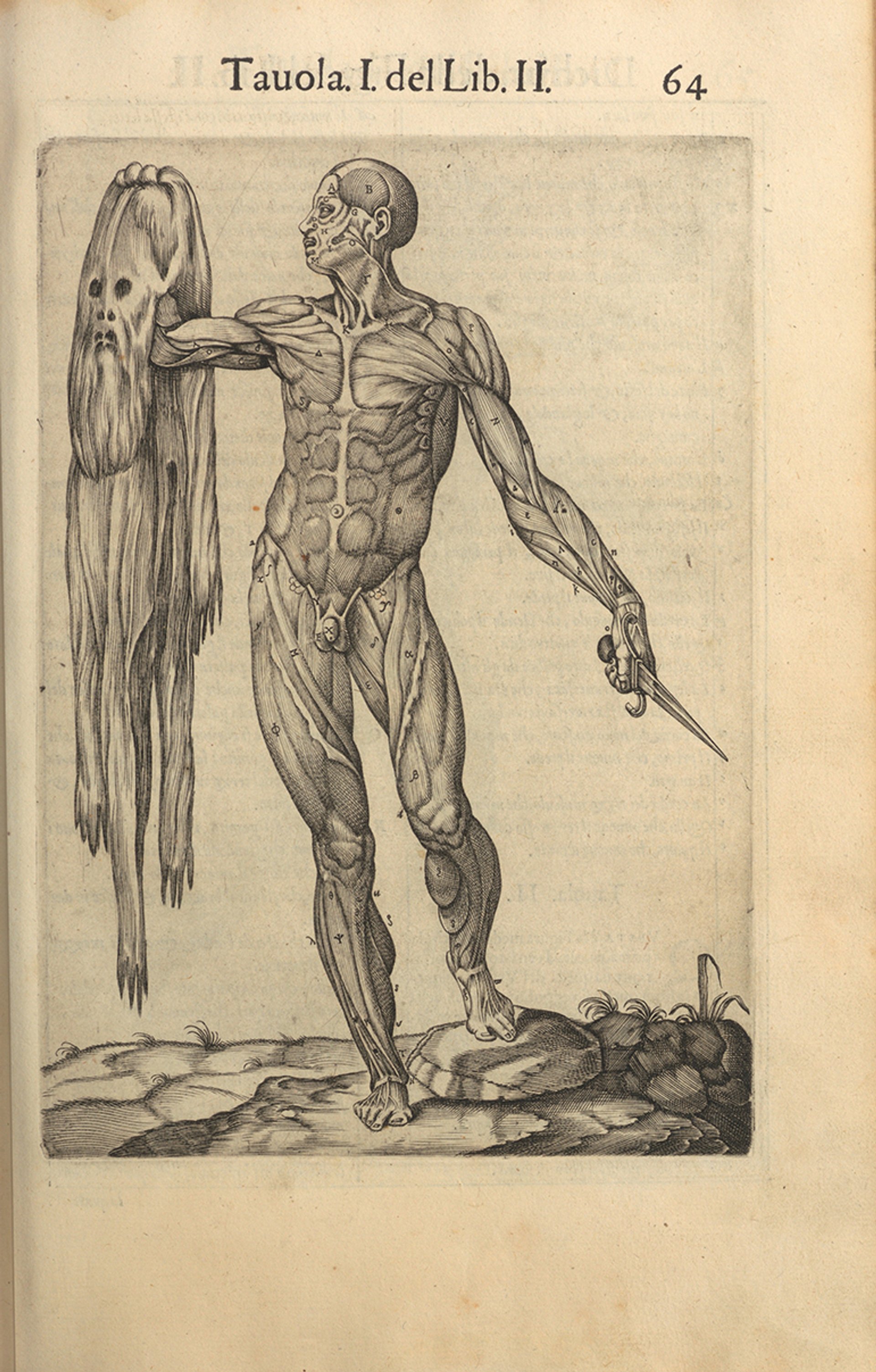

Juan Valverde de Amusco’s copperplate engraving Anatomia del corpo humano (1560), at the Library of Medicine in Bethseda, US National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, Maryland

Skin as matter

Part two develops Welch’s theme of the “period body” by investigating how people experienced both human and animal “skin as matter”. Chapters five and six assess the overlaps between medical and cosmetic treatments in the work of barber-surgeons, as well as bathing, cleansing and laundering, and the use of perfumes to shield the body’s exterior by creating an “all-enveloping atmosphere that would combat the cold, wet, pathogenic smells of decaying and disease-inducing air”. Along with clothing and wigs that protected the skin, Welch explores the use of facial adornments, including “vizard” masks for women, held (uncomfortably) in place by clenching a beaded mouthpiece between the teeth, and the popular fashion for black velvet patches in varying shapes, satirically dubbed mouches (flies), which were stuck to the face to disguise imperfections; both items were subject to moralist opprobrium on the grounds of female deceit and vanity. In chapters seven and eight, Welch turns to the skin of animals, looking initially at the myriad uses of local and imported leathers and furs, and the associated specialist trades that produced everything from muffs, gloves and military buff coats to parchment and wall-hangings. Welch then moves on to the handling of skin and flesh in the preparation of food, including hunting, butchery and cooking, and the broad range of knives developed to cut through the skin that were accompanied by illustrated manuals on the “anatomical art” of carving both meats and fruits. She notes that scientists such as the Brussels-born Andreas Vesalius (1514-64) and the Frenchman René Descartes (1596-1650) studied butchers to research dissection techniques, while in art, genre paintings of kitchen scenes and market stalls allowed contemporary artists to display their detailed anatomical knowledge, as well as their skill at rendering different surface textures, from fur and flesh to feathers and fish scales.

Medical progress

In part three, “Skin as Knowledge”, Welch considers various factors that accelerated scientific discoveries on the workings of the body and how this information was disseminated, starting with widely distributed illustrated publications, such as Vesalius’s ground-breaking study of human anatomy De Fabrica (1543), and also popular “flap books” intended for a non-academic readership, with paper sections that could be lifted to reveal the internal organs beneath. The development of microscopy also made skin a new focus of scientific enquiry, rather than something to be “stripped away and set aside” by anatomists. Specialist and non-specialist alike might attend the growing number of public dissections in anatomy theatres, salons and royal courts, or examine preserved human and animal skins in private collections. These advances were fuelled by competition between the new scientific academies established across Europe with the support of aristocratic patrons, such as the Royal Society of London (founded in 1660), at a time when “experimental science had become increasingly essential to the reputation of ambitious monarchs and elite courts”. In chapter 11, Welch explores changing attitudes towards skin colour as the rise of the slave trade and colonial expansion increased the number of non-white people encountered by Europeans. She looks at various examples, including tattooed Indigenous people exhibited as “marvels”, visiting African dignitaries and the fashion for Black attendants frequently pictured with elite white women. She also discusses the history of galley slaves in the Mediterranean, specifically at the Medici port of Livorno, and traces how “negative classical and biblical sources [were woven] into racializing narratives” that underpinned the exploitation of people with non-white skin. The final chapter presents an itch-inducing discussion on lice, focusing on the controversial microscopic discovery that scabies was caused by a tiny mite that laid its eggs under the skin, rather than corrupted internal humours generating “worms in the blood”, and notes that domestic treatments provided by women, who pricked out the mites with needles, were significantly more effective than the medications prescribed by learned physicians.

Welch’s rich and fascinating survey covers considerable ground and provides accessible introductions to a variety of topics. Quoting from multiple contemporary sources, the book functions as a useful guide to understanding approaches to medicine in the early modern period, while also charting how this knowledge developed during an era of scientific and cultural change. Welch observes that domestic practices and everyday experiences are often hard to trace, as they were rarely recorded for posterity. She counters this by drawing on a wide range of reference material—especially from the visual record—to illustrate the various subjects addressed across the chapters, which collectively investigate skin as “a complex boundary between concealment and revelation that continued, and continues to this day, to challenge easy categorisation”.

• Evelyn Welch, Renaissance Skin, Manchester University Press, 400pp, £150 (hb)/£55 (pb), published 1 July

• Sarah McBryde is an independent scholar and series assistant editor for Elements in the Renaissance (Cambridge University Press)