“That everybody could receive something without anyone having to pay,” wrote Vilfredo Pareto (1848-1923), the Italian polymath, on the illusory allure of protectionism as the ideal vote-catcher.

As any British school pupil studying history will know, the repeal of the 1815 Corn Laws in 1846 under UK prime minister Robert Peel marked a turning point in the country’s economic policy. They may also be aware that Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations (1776) laid the theoretical foundations for that shift toward free trade. Fewer—unless they are studying economics—are likely to be familiar with David Ricardo’s Principles of Political Economy and Taxation (1817), which provided a more formal theory of comparative advantage that has stood the test of time as a model for understanding the benefits of international trade.

Over the two centuries since, as the global population has increased fivefold, per capita income has risen more than eightfold—over 15 times the rate of the previous 800 years. In short: trade enriches.

Tariff threat

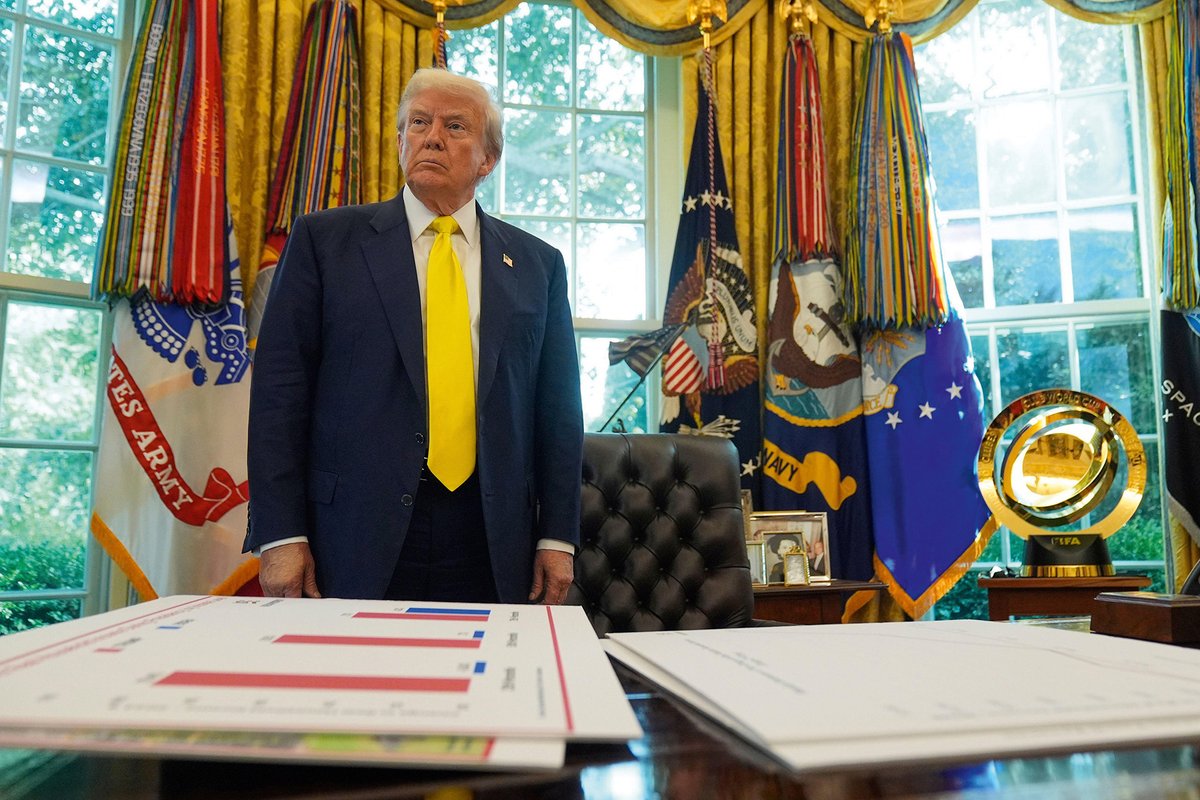

All this provides cause for concern in the wake of US President Donald Trump’s new global tariffs, announced in August, which raise import taxes on goods to their highest level since 1933, according to Yale University’s Budget Lab. As the world’s largest economy, the US consumes roughly one-third of global goods and services, making such policy shifts significant for all. This includes the art trade; the US has been the world’s largest art market since at least the Second World War.

Trump’s stated aims included import substitution, job creation, increased tax revenues and ultimately the reduction of global tariffs. However, most economists predict the opposite: a contraction in trade, rising prices, and potential job losses depending on the international response.

This raises several important questions: Why does this matter to the art market? What can we learn from history? And how might this temporary or permanent setback be overcome?

Throughout its history, the art market has thrived on financial surpluses and the free movement of goods and people—both of which are products of international trade. The market tends to flourish during periods of population growth, economic expansion and free trade, especially toward the end of an economic cycle. Since the 1960s, when international trade in art and collectibles was first systematically measured, the market has grown with each passing decade, often in higher bursts of two to three years. Over that time, the number of countries participating in the international art trade has increased fivefold, with several developing economies emerging as major players.

How protectionism affects the art market

History offers two key periods in which tariffs clearly affected the art market: the late 19th to early 20th centuries, and the inter-war years of the 1920s and 30s.

In the first period, tariffs among 35 countries rose from the 1860s, reaching over 15% by the 1880s and into the 1910s—particularly in Latin America and peripheral Europe. In the US, import tariffs were raised in 1861, peaking at 47% later that decade, before stabilising at an average of 20% to 30% by 1913. Dutiable import tariffs peaked at 52% in 1897. Elsewhere, countries such as Russia, Spain, Japan, Sweden, France, Italy and Austria-Hungary selectively raised tariffs from 1875, reaching ranges of 20% to 84% by 1913. By contrast, the UK maintained a policy of free trade, while the Netherlands, Belgium and Switzerland kept tariffs relatively low.

Protectionist thinking in this era drew on earlier economic writings, notably of Alexander Hamilton in the US and Friedrich List in Germany. Their arguments focused on nurturing “infant industries” and promoting the nation-state over global integration. Language trends in English-language books support this shift in sentiment: the use of the word “protectionism” rose steadily from 1840 to 1910, accelerating in subsequent decades. Conversely, the phrase “free trade” gained ground from 1790 to 1870 before tapering off and declining by 1910.

The US enjoyed certain advantages during this period: a vast domestic market, relatively low international dependency and a tradition of isolationism. Tariffs were a primary source of federal income until the First World War. Customs revenues were actually higher in real terms in 1913 than in 1835. Indeed, average US tariffs in the 19th century were higher than at any time since—until Trump’s recent proposals.

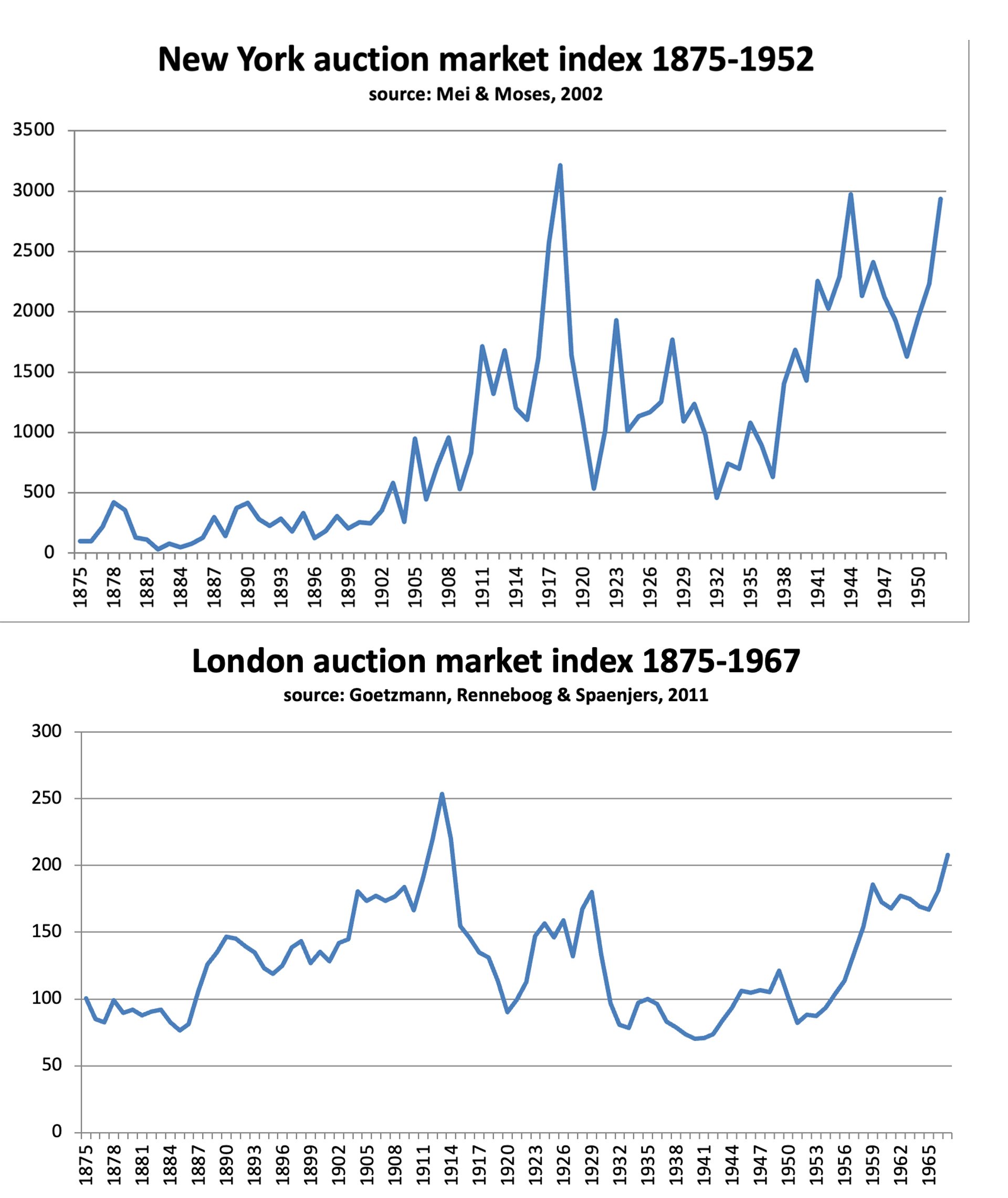

While other factors also influenced the art market—such as domestic taxation and cultural preferences—it is clear that protectionism created a more volatile, less confident international business climate. In the UK, art imports boomed in the 1850s and 70s but declined as the “long depression” of the late 19th century set in. Auction numbers surged in the 1850s and again from 1874 to 1888, peaking by 1913. In continental Europe, more protectionist economies saw auction growth from 1870 to a peak in 1883, followed by a larger surge from 1901 to 1913. Auction prices reflected this volatility: after rising in Britain from the 1840s, they slumped in 1875-85, surged and fell again in 1891-1901, and hit a much higher peak in 1913. In the US, auction price cycles were more frequent and subdued until around 1903, after which they rose to a peak in 1918—as tariffs fell to their lowest in a century.

The disaster of the Great Depression

The second era of protectionism is more familiar, though overshadowed by the Great Depression, of which it was a contributing factor. US tariffs, lowered after the First World War, were reintroduced in 1922 and steadily increased through the decade, culminating in the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930—a policy that the noted British civil servant Arthur Salter would later call “a turning point in world history”. These measures largely aimed to protect American agriculture, which had suffered a boom-bust cycle from 1915 to 1929.

The result was disastrous. Global trade collapsed by 25% between 1929 and 1934 due to higher tariffs, import quotas and currency controls. The 1934 Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act aimed to reverse some of the damage. Meanwhile, countries including the UK introduced even higher tariffs than the US, attempting to protect themselves from deflation while constrained by fixed exchange rates under the Gold Standard. The Gold Standard became the basis of the international currency system from 1873 with the aim of stabilising prices and facilitating borrowing. Ultimately, those who abandoned the gold peg and pursued expansive monetary policy recovered faster.

© James Goodwin

This economic turbulence harmed the art market—though less so in the UK and the US than during the earlier era. In the UK, auction prices fell by over half after peaking in 1913, doubled in the 1920s, then collapsed again after 1929. They only recovered to their 1929 level by 1959—and to their 1913 level by 1967. In the US, prices peaked in 1918, fluctuated until 1929, fell sharply between 1929 and 1932, then recovered in stages in 1933 and 1935, reaching a higher peak in 1941. But it took until 1953 to return to 1918 levels.

Different sectors of the market were affected in different ways. The old adage that collectors buy new works in good times and Old Masters in hard times held true. In the 19th century, the Old Master market thrived from 1815 to the 1880s, while the British school of portraiture held on into the 20th century. The primary market peaked in the UK in the 1860s but gave way to European art, which would not be appreciated on resale until decades later. Museum building in Britain also buoyed the market.

The 1920s saw dramatic shifts in taste: the Barbizon school and John Singer Sargent fell out of fashion, while 18th- and early 19th-century British artists—Reynolds, Gainsborough, Constable and Turner—rose in popularity. In the 1930s auction turnover declined overall. Rembrandt and Van Dyck faded in demand, while the Italian Primitives, 16th-century Venetians and Rubens and other 17th-century Dutch painters gained ground. Meanwhile, Impressionism began a long ascent in value, and Modern art attracted growing interest, reflected in museum acquisitions at the time.

Income diversification

The primary market was equally dynamic. Despite hardship, Modernism flourished across Europe, the US and Asia. Many artists supplemented their incomes through design, advertising and teaching, yet the 1930s still saw major exhibitions of Picasso and the emergence of a new generation of American Modernists—laying the groundwork for the post-war art boom under renewed free trade.

In the present, it is to be hoped that President Trump’s tariff experiment will eventually be reversed or lead to lower global tariffs, as occurred in earlier episodes of protectionism. If not, we might take inspiration from the resilience of the 1930s art world, when artists, dealers, auctioneers and curators adapted and diversified to survive—producing, selling and exhibiting works that spoke to both crisis and hope.

In today’s context, we may find ourselves buying more art from less familiar regions of the world, albeit with fewer opportunities to resell into the dominant US market—and thereby at lower prices. Still, as the developed world plus China ages and slows, and as younger, faster-growing economies expand, that strategy may prove wise in the long run.