On Indigenous Peoples’ Day (13 October), 17 Native artists staged an unsanctioned intervention inside the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s American Wing. Using augmented reality (AR), the artists intervened in the gallery’s 19th-century paintings—generic and imagined landscapes, portraits of affluent settlers and grandiose historical scenes—digitally superimposing cosmological figures, pow-wow dancers and suffocating layers of ivy.

The unsanctioned digital intervention, ENCODED: Change the Story, Change the Future (until 31 December), was co-curated by the film-maker and curator Tracy Renée Rector and an anonymous Indigenous co-curator (who also sponsored the project), in collaboration with the non-profit media and design lab Amplifier. It launches as the American Wing celebrates its centenary, asking: what stories does American art tell? Who decides what’s worthy of display? And what happens when the museum will not make room, so artists take it?

The project comes as the Met has taken some steps towards fostering a sense of belonging for Native art and artists in the American Wing. In 2020 the museum hired Patricia Marroquin Norby as its first associate curator of Native American art. In 2021 it debuted a new display of the Charles and Valerie Diker collection of 139 works from more than 50 tribes, though the works have been displayed in a segregated corner of the American Wing. Earlier this year, the museum opened a survey devoted to the Ojibwe Abstract Expressionist painter George Morrison (until 31 May 2026), curated by Norby. But it was installed in a room adjoining the Diker collection works, cloistered from Morrison’s 20th-century New York contemporaries like Helen Frankenthaler, William T. Williams and Jackson Pollock.

Flechas, LANDBACK (2025), digitally overlaid on Emanuel Leutze's Washington Crossing the Delaware (1851) at the Metropolitan Museum of Art Courtesy the artist and Amplifier

“Institutions have a responsibility to care for the community that they represent, or have taken culture from,” Nicholas Galanin, a Tlingit and Unangax̂ artist who contributed multiple works to ENCODED, tells The Art Newspaper.

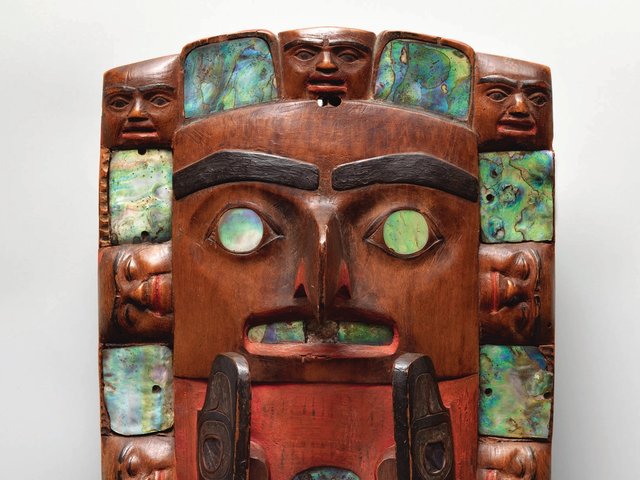

Galanin’s enduring dubiousness about institutional collecting practices informed one of his previous works, Anax Yaa Nadéin (it is flowing through it) (2022), a series of masks and baskets with balaclava-style eye and mouth openings. The piece points to the double standard in how the theft of Native cultural objects sanctioned by and for the West is perceived, compared to the criminalisation of Natives who might reclaim those same objects by similar means. Galanin’s critique is backed by data: research by ProPublica shows that only 15% of the 139 Indigenous works in the Diker collection have solid or complete provenance. The the Native American Grave Protection and Repatriation Act was updated in 2023 to require deference to tribes’ Indigenous knowledge and authority in the return of human remains, funerary items, sacred objects and objects of cultural patrimony.

“Museums are nimble when they really want to be—this is how they get their things done,” Galanin adds.

Priscilla Dobler Dzul's Future Cosmologies: The Regeneration of Maya Mythologies (2023) digitally overlaid on Thomas Crawford's Mexican Girl Dying (1846, carved 1848) at the Metropolitan Museum of Art Courtesy the artist and Amplifier

Not all the participants in ENCODED see the Met as an adversary. The Seneca-Cayuga artist Amelia Winger-Bearskin, who uses artificial intelligence as a creative medium, describes a more nuanced relationship to the institution.

“I have a beautiful relationship with the Met growing up in New York. My son took classes there. I had a friend who led an art and tech incubator inside the Met when they had a grant to look at emerging technologies,” Winger-Bearskin says. “The Met has always taught me how to interact with it. I think it’s set up for these types of interactions—building this AR layer on top of it to expand these conversations.”

The interventions themselves are both playful and pointed. Visitors can use a link for a self-guided tour on their phones, activating these virtual transformations as they traverse the American Wing and the Met’s exterior by holding up their phones before select works. For his contribution, the Shinnecock photographer Jeremy Dennis transposed the White House on top of a painting of the Parthenon, showing the same disregard for Western sacred sites that has been shown to Native ones––such as the defacing of the Black Hills to create Mount Rushmore. Priscilla Dobler Dzul digitally enrobed Thomas Crawford’s sculpture Mexican Dying Girl (1846-48) in a florally embellished funerary big cat skin, head and all.

Jeremy Dennis's The White House (2025) digitally overlaid on Frederic Edwin Church's The Parthenon (1871) at the Metropolitan Museum of Art Courtesy the artist and Amplifier

Some artists’ jocose transformations work through wordplay, like Mer Young transposing a famous photograph of We'wha—a Zuni two-spirit artist and spiritual leader who travelled to Washington, DC, in 1886—over Childe Hassam’s Avenue of the Allies, Great Britain (1918). The original painting depicts a patriotic display of flags from European and Latin American nations along Fifth Avenue in support of US involvement in the First World War. These nations were no allies to queer Indigenous people, and Young’s intervention offers a pointed play on the contemporary LGBTQIA2S+ language of allyship.

“I wanted to make sure the artists could represent themselves as they wanted,” Rector says. “A throughline was cosmology: not only responding to American masters, but opportunities to show ways of resistance and not just reframing but creating new narratives.”

In reference to the project’s unsanctioned nature, Record adds: “About five years ago the Met worked with a number of placards that offered a Native perspective on pieces of art. Those are no longer up. I’d love institutions, especially the Met, to bring back that counterbalance. As we know, history is often told by the winners or those in power.”