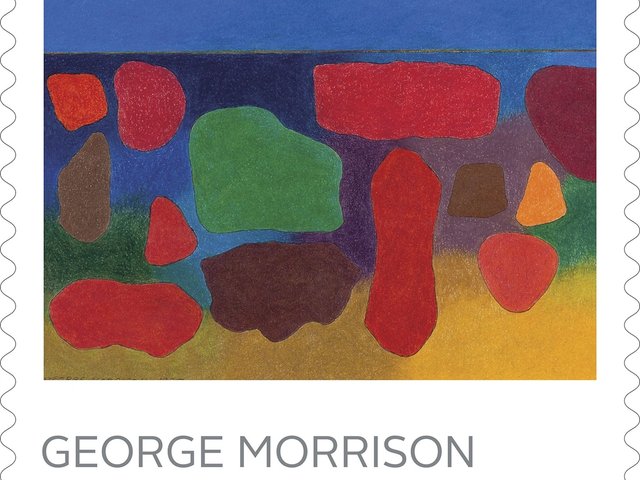

Abstract Expressionism is often thought of as the story of white men flinging paint in New York City, the very definition of postwar American art. But where are the Native Modernists? If the Tecolote Cave pictographs from 7300BC and 19th-century Sioux women’s ceremonial objects demonstrate similar geometry, chromatic restraint and spatial rhythm to that celebrated in the art of Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko, is American Modernism not indebted to Native art? A new exhibition of works by the Ojibwe abstract painter George Morrison (1919-2000) at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art may serve as a key to answering this important question.

The artist’s largest show to date, The Magical City: George Morrison’s New York (until 31 May 2026), is also rather intimate. With its 25 works on view, together with archival materials, the exhibition stages a central tension in Native life: the city and the reservation—in this case, New York City and the Grand Portage Chippewa reservation on Lake Superior. But the phrase “walking in two worlds”, which the historian Vine Deloria Jr derided for masking Native sovereignty’s fractures, hardly applies here. (The title of the show comes from Morrison’s own words: he called New York a “magical city”.)

Installation view of The Magical City: George Morrison’s New York at the Metropolitan Museum of Art Photo: Paul Lachenauer, courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Morrison’s Abstract Expressionism flouts these cleavages with sumptuous irony: lush, often warm colours that idealise landscapes and urban scenes even as they expose the confrontational realities of displacement, prejudice and survival. Born into poverty on the Grand Portage reservation, by the time the artist moved to New York in 1943, he had already survived severed hair, cultural obliteration and tuberculosis—what worse could the city have to offer? His works’ titles alone reveal this duality: The Antagonist (1956) versus Autumn Dusk, Red Rock Variation: Lake Superior Landscape (1986), gesturing between the bigoted and the bucolic, the urban and the homeland. In Aureate Vertical (1958), the blindingly idyllic gleam of golden glass skyscrapers belie how the city streets can sweep the viewer under as swiftly as the squally waters of Morning Storm, Red Rock Variation: Lake Superior Landscape (1986).

Morrison belonged to a cohort of mercurial male Abstract Expressionists lionised through the postwar “tortured genius” myth. He was close with artists like Willem de Kooning and Franz Kline, as well as with Lois Dodd and Louise Nevelson. Unsurprisingly, self-destructive behaviour was only tolerated along strict gender and racial lines. Elaine de Kooning, Grace Hartigan and Morrison—who survived both crippling childhood illness and an Indian boarding school—did not publicise or mythologise their own mental health. The Victorian notion of hysteria pathologising women and people of colour still persisted.

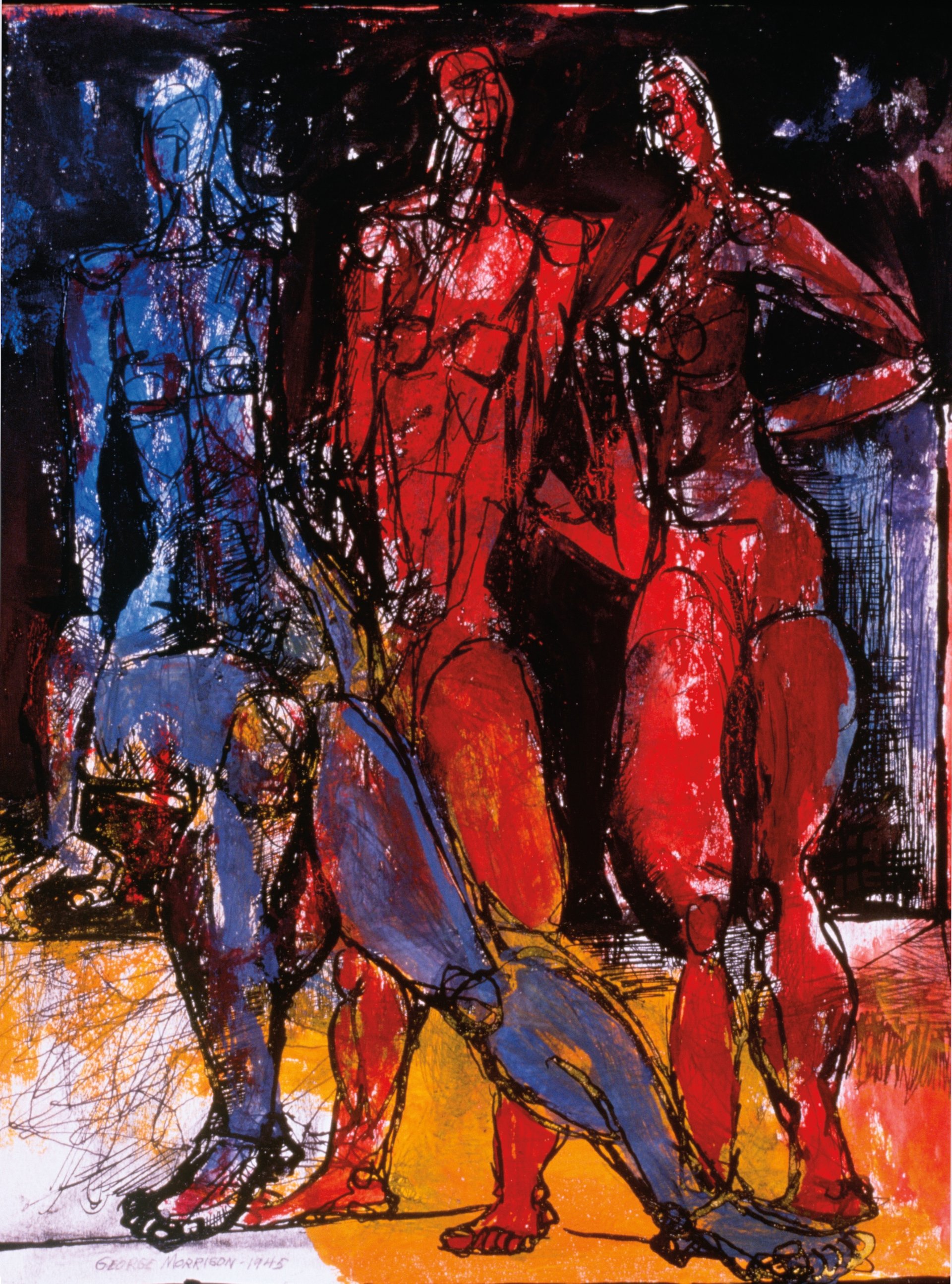

Morrison’s work exposes a quiet, complex interiority resisting easy mythologising, but there is a rugged, sultry edge beneath its surface. Though the artist was reserved in demeanor, his palette and subjects betray a rich romantic and spiritual life. Three Figures (1945), for example, deploys saturated figures in red and blue against a dark background to depict a volatile love triangle he experienced while studying at the Art Students League in New York.

George Morrison’s Three Figures (1945) Minnesota Museum of American Art, Saint Paul. © George Morrison Estate

Morrison’s work has always been arresting. Willem de Kooning was so awed by what he saw in a 1945 group show that he fell uncharacteristically silent. In Morrison's first five years in New York, his work beguiled institutions too, travelling from the Whitney Museum of American Art to the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis and Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia.

Morrison’s shift from representation to gut-wrenched gesture can be seen in the watercolour-and-ink Dream of Calamity (1945), a distressed response to the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The painting drew critics’ attention with its disjunctive web of lines and smoky dulled colours swirling over Japanese homes. Unlike the works of many canonical Abstract Expressionists, Morrison’s carried direction: the long horizon line, a distance just out of reach. Perhaps this was an escape from post-traumatic stress. The then-nascent city therapy scene was too bourgeois to offer relief. Morrison would instead find healing through transformation—not of trauma, but of place.

George Morrison’s Dream of Calamity (1945) Tweed Museum of Art, University of Minnesota Duluth. © George Morrison Estate

Take Structural Landscape (Highway) (1952), for example. The painting mutates the West Side Elevated Line (now the High Line), turning a train route into a neutral geometry abutting a lush New Jersey waterfront with no river in between. Here Morrison offers viewers the comfort of recognition—the West Side, the Holland Tunnel—yet he employs a spatial strategy eliding watery hues to make the verdant Garden State appear intimate, within reach. The land is there. The truth is there. Neither hidden nor spelled out.

Against Morrison’s layered inwardness, his peers’ works feel oddly hollow. Pollock, Barnett Newman and Peter Busa filled their canvases with borrowed gestures from the very Native sources Morrison drew on, yet they somehow produced glib facsimiles. The cultural emptiness of Morrison’s contemporaries reflected a broader spiritual dislocation in non-Native America that, unfortunately, still exists today.

George Morrison’s Structural Landscape (Highway) (1952) Joslyn Art Museum, Omaha, Nebraska. © George Morrison Estate

Though Morrison learned classical techniques, he moved towards abstraction—perhaps to transcend the confines of realism in life and painting. Imbuing emotion into each stroke and line with mathematical precision, Morrison depicts landscapes from the Big Apple to Chippewa territory, drawing shockingly clear visual and ontological lines with both organic and engineered horizons. (After all, everything in the metropolis, even the steel and glass of the Empire State Building, originated in nature.)

But Native art still remains sidelined—separated from the Modernist canon it helped shape, too often confined to isolated museum wings and galleries. Despite decades of progress and intermittent visibility, Native art’s full recognition remains a work in progress. Even with the Morrison exhibition, the show’s placement in the American Wing—abutting the Met’s Native collection rather than among Morrison’s white contemporaries—suggests the institutional challenges that the curator Patricia Marroquin Norby navigated in securing parity for the artist. The Met’s placement exposes a persistent fiction: that contemporary Native art belongs to history, not the present.

- The Magical City: George Morrison’s New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, until 31 May 2026