The new film Moss & Freud opens with Kate Moss (Ellie Bamber) hurtling down the motorway, cigarette in hand, blond hair whipped back, redoing her lipstick in the rear-view mirror like a Hitchcockian anti-heroine. When sirens peal behind her and the police pass, Moss cackles. This sequence establishes the film’s fixation as being on the model and unlikely, one-time muse of Lucian Freud (here Derek Jacobi), rather than on the artist. Sadly, it has little to say about either subject—or Freud’s self-proclaimed search for “truth” through art.

The film, a feature-length debut for writer-director James Lucas, is set in London in 2001. As per the title, its story centres on the unlikely friendship forged between a reclusive Freud, by then in his late 70s, and a 27-year-old Moss, fatigued by relentless fashion editorials and partying. After the English model mentioned in a Dazed & Confused interview that she would like to sit for Freud, the portraitist—famously reluctant to paint anyone outside his close circle—agreed, culminating in the stark, corporeal and ruthlessly unflattering Naked Portrait 2002. You might expect Moss & Freud to provide a similarly complex treatment of its characters: it proves, however, more a flattening than illuminating portrait of an artist-sitter dynamic.

Lucas has them first meet in an empty National Gallery in the early hours, Moss hungrily eyeballing the delicately painted faces in the 17th and 18th century rooms. Freud waits for her by Titian’s Diana and Actaeon; he relates to the latter, he chuckles, because of the “silliness of the man”. And the disparity between them—Moss with her raspy drawl, fur coat and flighty manner, and a fuddy, beige-dressed Freud—is implied throughout the film to be the same as the subject of this work: that of coarse, besotted hunter intruding on a goddess’s sphere.

Yet while Moss is chided for being five minutes late as she is shown in by Freud’s loyal assistant David Dawson (Tim Downie)—the harsher elements of the artist’s austere reputation are otherwise eroded. There is no sense of the potential toll of his punishingly long sittings, which in Moss’s case lasted from 7pm to 2am over the course of nine months, while she was pregnant. Lucas also smooths over his reputed darker habits, including a capacity for cruelty and even violence. Rather than being a stickler for routine, he is portrayed as a benign, mildly eccentric sweet-hearted old man—highly sympathetic to the life of a model and happy to play the clown to boost her mood.

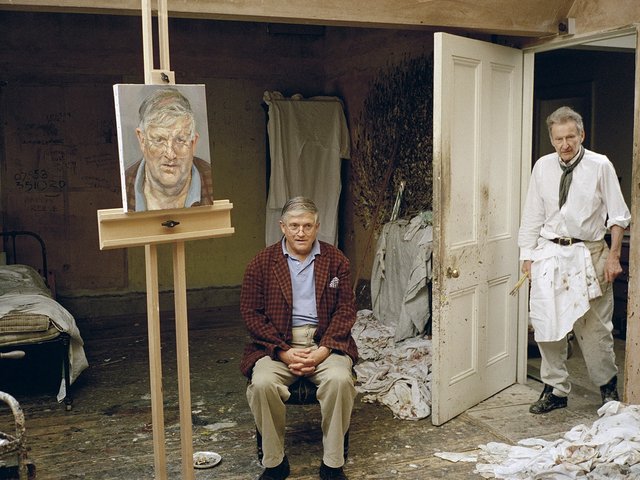

Derek Jacobi as Freud in his studio

Photo: courtesy LFF

The heavier details from Freud’s biography are also glossed over. Heritage was a thorny topic for the artist and one he rarely spoke about publicly; but in one abrupt scene in a Mayfair restaurant–only Moss and Freud’s second meeting–the artist divulges, matter-of-factly, how his Jewish family fled Nazi Germany for St John’s Wood in 1933. It's a fleeting moment in which this Freud feels detached from the shy, melancholic man who spoke in the artist’s sole full-length interview in 1988. Much is made, meanwhile, of his short-lived marriage to the author Lady Caroline Blackwood, nodded to in melodramatic flashbacks. Forced parallels are drawn between her and Moss—writer and model, two adrenaline-chasing socialites—and used to explain his spiralling infatuation with the latter.

Moss & Freud’s shortcomings are ultimately owing to the weakness of its script. It references–and often rehashes–Freud’s lyrical writings on art theory—Jacobi quoting Freud’s words verbatim to fit the story. It also glances over the superficiality and exploitation of the fashion scene Moss turns away from, while portraying–but not investigating–her rather inflated sense of self-importance. Lucas, a former assistant editor at Tank Magazine and screenwriter of the lauded feature Whina (2022), enlisted Moss as executive producer. And Bamber (Nocturnal Animals, 2016) and Jacobi (Gosford Park, 2001, Hamlet, 1996) strive to make the most of this thin material, but the characters don’t make it beyond hollow caricatures.

Credit must go to cinematographer Maria Ines Manchego, whose camera replicates the slanting, off-kilter angles of Naked Portrait 2002 and other works by Freud such as After Cézanne, and glides seamlessly over the shimmering surfaces of sartorial shoots and runways. From charcoal to impastoed oils, Downie–who assisted on the original work–also recreates the portrait’s progress with painstaking accuracy throughout the film’s runtime, giving some insight into the artist’s process.

Moss & Freud seems to want to tell the story of an artist stripping back the layers of a woman’s celebrity to expose the “ordinariness” of the person beneath. But those hoping to discover a greater truth about either artist or sitter in this airbrushed portrait will have better luck looking at the works themselves.The new film Moss & Freud opens with Kate Moss (Ellie Bamber) hurtling down the motorway, cigarette in hand, blond hair whipped back, redoing her lipstick in the rear-view mirror like a Hitchcockian anti-heroine. When sirens peal behind her and the police pass, Moss cackles. This sequence establishes the film’s fixation as being on the model and unlikely, one-time muse of Lucian Freud (here Derek Jacobi), rather than on the artist. Sadly, it has little to say about either subject—or Freud’s self-proclaimed search for “truth” through art.

The film, a feature-length debut for writer-director James Lucas, is set in London in 2001. As per the title, its story centres on the unlikely friendship forged between a reclusive Freud, by then in his late 70s, and a 27-year-old Moss, fatigued by relentless fashion editorials and partying. After the English model mentioned in a Dazed & Confused interview that she would like to sit for Freud, the portraitist—famously reluctant to paint anyone outside his close circle—agreed, culminating in the stark, corporeal and ruthlessly unflattering Naked Portrait 2002. You might expect Moss & Freud to provide a similarly complex treatment of its characters: it proves, however, more a flattening than illuminating portrait of an artist-sitter dynamic.

Lucas has them first meet in an empty National Gallery in the early hours, Moss hungrily eyeballing the delicately painted faces in the 17th and 18th century rooms. Freud waits for her by Titian’s Diana and Actaeon; he relates to the latter, he chuckles, because of the “silliness of the man”. And the disparity between them—Moss with her raspy drawl, fur coat and flighty manner, and a fuddy, beige-dressed Freud—is implied throughout the film to be the same as the subject of this work: that of coarse, besotted hunter intruding on a goddess’s sphere.

Yet while Moss is chided for being five minutes late as she is shown in by Freud’s loyal assistant David Dawson (Tim Downie)—the harsher elements of the artist’s austere reputation are otherwise eroded. There is no sense of the potential toll of his punishingly long sittings, which in Moss’s case lasted from 7pm to 2am over the course of nine months, while she was pregnant. Lucas also smooths over his reputed darker habits, including a capacity for cruelty and even violence. Rather than being a stickler for routine, he is portrayed as a benign, mildly eccentric sweet-hearted old man—highly sympathetic to the life of a model and happy to play the clown to boost her mood.

The heavier details from Freud’s past are also glossed over. Heritage was a thorny topic for the artist and one he rarely spoke about publicly; but in one abrupt scene in a Mayfair restaurant–only Moss and Freud’s second meeting–the artist divulges, matter-of-factly, how his Jewish family fled Nazi Germany for St John’s Wood in 1933, devoid of the shy melancholy with which Freud spoke of it in his sole full-length interview in 1988. Much is made of his short-lived marriage to the author Lady Caroline Blackwood, nodded to in melodramatic flashbacks. Forced parallels are drawn between her and Moss—writer and model, two adrenaline-chasing socialites—and used to explain his spiralling infatuation with the latter.

Moss & Freud’s shortcomings are ultimately owing to the weakness of its script. It references–and often rehashes–Freud’s lyrical writings on art theory—Jacobi quoting Freud’s words verbatim to fit the story. It also glances over the superficiality and exploitation of the fashion scene Moss turns away from, while portraying–but not investigating–her rather inflated sense of self-importance. Lucas, a former assistant editor at Tank Magazine and screenwriter of the lauded feature Whina (2022), enlisted Moss as executive producer. And Bamber (Nocturnal Animals, 2016) and Jacobi (Gosford Park, 2001, Hamlet, 1996) strive to make the most of this thin material, but the characters don’t make it beyond hollow caricatures.

Credit must go to cinematographer Maria Ines Manchego, whose camera replicates the slanting, off-kilter angles of Naked Portrait 2002 and other works by Freud such as After Cézanne, and glides seamlessly over the shimmering surfaces of sartorial shoots and runways. From charcoal to impastoed oils, Downie–who assisted on the original work–also recreates the portrait’s progress with painstaking accuracy throughout the film’s runtime, giving some insight into the artist’s process.

Moss & Freud seems to want to tell the story of an artist stripping back the layers of a woman’s celebrity to expose the “ordinariness” of the person beneath. But those hoping to discover a greater truth about either artist or sitter in this airbrushed portrait will have better luck looking at the painting.