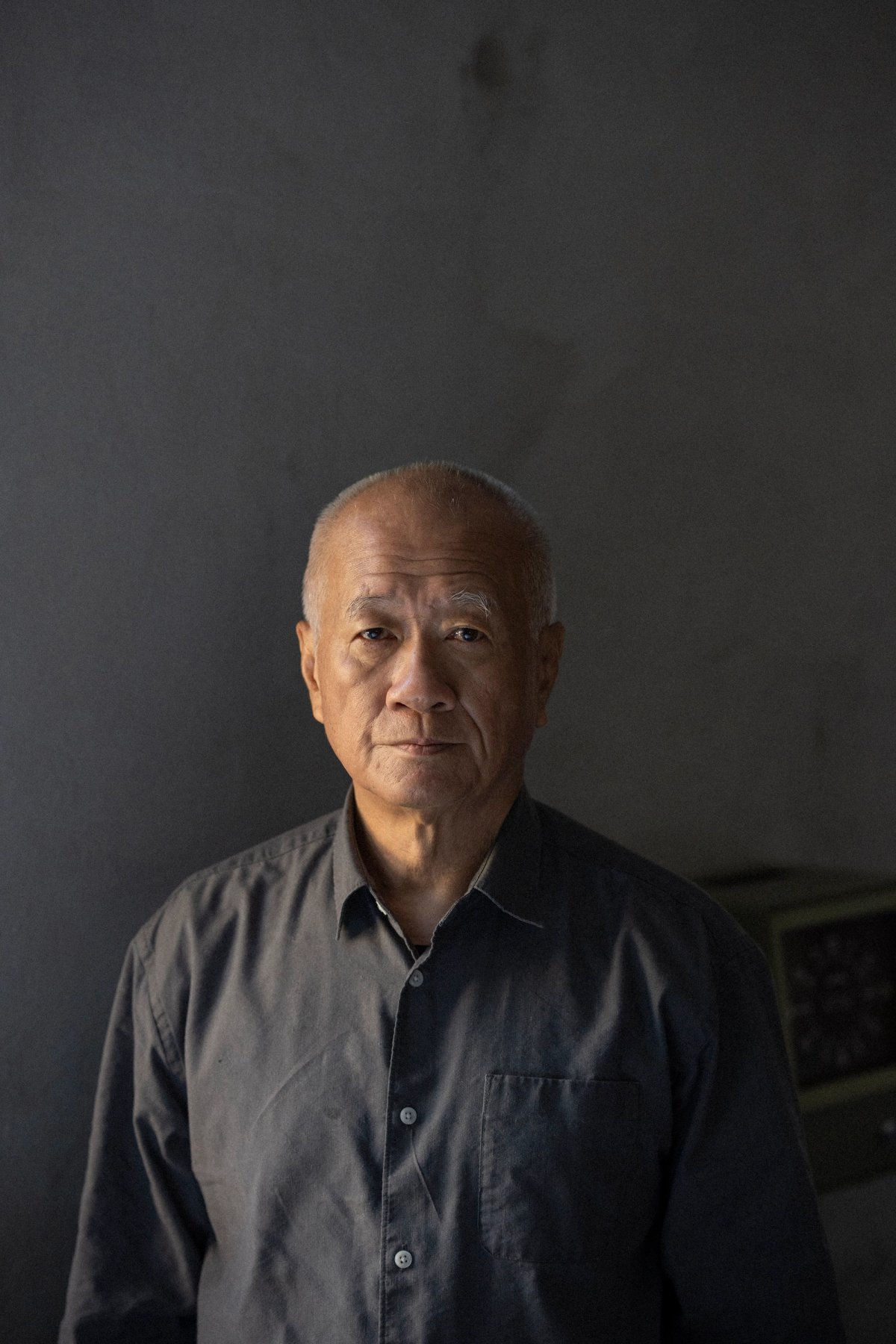

The pioneering performance artist Tehching Hsieh is renowned for creating six extraordinary works subjecting himself to conditions of intense confinement, exposure, sleep deprivation and intimacy. He was born in Taiwan in 1950 and although he began his career as a painter, his reputation was made following his move to New York in 1974 where he began making a series of groundbreaking performance pieces.

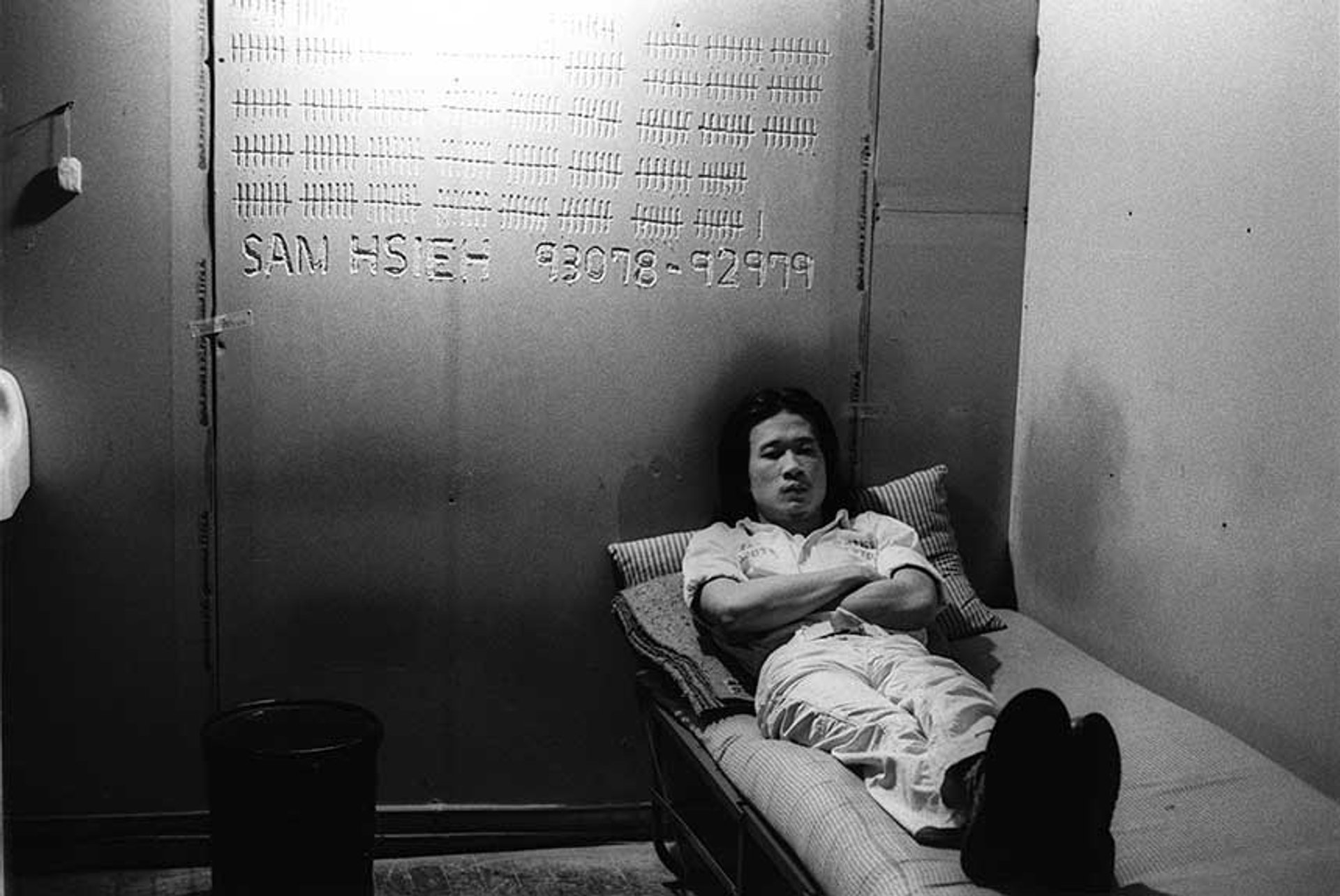

In 1978 Hsieh embarked on a sequence of five performance works each lasting a year, beginning with Cage Piece, where he lived locked in a wooden cage in his apartment for one year, never coming out and never reading, writing, talking, listening to music or watching television. His meals were delivered to him daily and his excrement taken out in a bucket. This was followed by Time Clock Piece (1980-81), where the artist punched in a time clock every hour for a whole year; Outdoor Piece (1981-82), where he lived outdoors in New York for a year; Rope Piece (1983-84), which entailed being tied to fellow artist Linda Montano for a year, without touching each other; and finally No Art Piece (1985-86), a year in which Hsieh did not make, talk about, or look at art. His final major performance piece, Thirteen Year Plan (1986-99), consisted of making art privately for 13 years and then revealing the result to the public—which took the form of a statement that said, “I kept myself alive”.

The first retrospective of these performances, Lifeworks 1978-99, recently opened at Dia Beacon following the artist’s gift of 11 major works to the institution last year. The exhibition has been designed to spatially convey the relative time it took to perform the works against time just living, which the artist refers to as “art time” and “life time” respectively. Hsieh explains that he did not want too much emphasis on the documentation of the works but instead wanted visitors to “see time and space”.

In Cage Piece (1978–79), Hsieh did not read, write, talk, listen to music or leave his wooden cage for a year

Photo: Claire Fergusson, Life Images; courtesy Dia Art Foundation; © Tehching Hsieh

The Art Newspaper: The Dia exhibition has been many years in the making, and you have been closely involved in every aspect. How has the show been organised?

Tehching Hsieh: Because it is difficult for humans to try and touch time, I now use space to present time and its documentation, with the days and years calculated into measurements. Dia is showing each of my six pieces of work that took 18 years in total [to create].

[In the exhibition] there are six spaces measured into “art time”—and the longer the work, the bigger the space to contain it. The gaps in between these containing spaces correspond to the intervals between my performances, which I call “life time”. But my fifth one-year performance [No Art Piece], when I did not do, talk, see or read art between 1985 and 1986, is communicated by an empty space that is both “art time” and “life time”.

The last and biggest space at Dia is taken up by the 13 years between 1986 and 1999 when I made art but away from public view. This too is both “art time” and “life time”. So, the Dia show is a frame of my art and life between those years. People can walk through the spaces with their own experiences and imagination and stay until they have too much of a headache! When they come to the last big empty room, maybe they can have a discussion or just think about what is going on.

At the very end there is a model of the spaces they have just walked through so they can digest what they have seen. I don’t want people just to be thinking about the documentation, I want people to think about time when they are in the space. People don’t need to know about art history to know my work, they only need life experience. They don’t need to think, “is it art or not art?”

Why was it so important that your performances were measured in years?

The time of one year was an important concept for me. I only know about experiencing time and it takes the earth a year to circle around the sun. It is the unit of the human calculation of life: how we count time, explain time and measure our existence. One year is a symbol for a whole life because the seasons repeat. To do a piece for one week is to perform, to separate my art and my life—but to do a piece for one year was more powerful and made art my life. But I didn’t try to be a superman, my work is not about heroism. For me, duration is the continuity of life, full of cycles, repetitions and rhythms. It is a human sense to understand life in time and to think about how you live in time. A century is another mark, which is how my last piece was created, to reach the frame of a century and the beginning of a new millennium.

A recreation of the site for Hsieh’s Cage Piece is part of the Dia Beacon exhibition. It was the first of a series of five of the artist’s year-long performance works Photo: Bill Jacobson Studio, New York; courtesy Dia Art Foundation; © Tehching Hsieh

It is also fortuitous that your birthday is on 31 December, the date many cultures make the change from the old year to the new one.

I don’t really celebrate birthdays. To me every day is the same. My last [performance] Thirteen Year Plan started on my 36th birthday and finished on my 49th birthday, 31 December 1999, to run up to the millennium. I chose 4 July, [US] Independence Day to start the Rope Piece and the Outdoor Piece started on the first Saturday of fall and had the rhythm of the four seasons.

Can we go back to the beginning? You were one of 15 children, growing up in Taiwan, with no artists in your family. What made you want to be an artist?

I was already good at painting. And in 1967 I quit high school and gave myself my own education and got more serious. I was inspired by Vincent van Gogh. His influence was not only his paintings but also his persistence in life. It was his lifework that was important for me. But I had to find my own way; I’m not good at being part of a system.

Later I realised that I couldn’t express my art through painting. So I stopped painting in 1973 and made some experimental action work. If people have a curiosity about this, I have a show of my early work opening next year in Taiwan. The work between 1978-99 didn’t just come, boom, out of nowhere—there was a long training. It was like an iceberg under the water. Franz Kafka became my teacher, I learned from him and also from Samuel Beckett what it is to be human and to do things. I learned it is not about success; it is just to understand life. But I had to find my questions and my answers myself. I wanted to come to New York because it was the world’s art centre, and I wanted to be a good artist.

You have said that your work is not autobiographical. But you have also said that Cage Piece and the physical hardship you put yourself through in the Time Clock and Living Outside was influenced by your experience of living and working as an illegal immigrant.

Nearly all the work shown in Dia was done in illegal time. I arrived [in the US] on 13 July 1974 and I was illegal with no passport for 14 years, until being granted amnesty in 1988. I was always thinking the authorities would kick me out. I was a dishwasher and cleaned floors in a Chinese restaurant. For the first four years I didn’t make art, I was working to survive and getting over the culture shock.

Was it not your intention to come to New York to make art rather than to earn money?

Instead of being a practising artist, I was a thinking artist. I had no idea how to start doing artworks, except for thinking. So for four years I was wasting time but also passing time. With the Cage Piece I became a practising artist and made thinking part of the practice.

When I say my work is not autobiographical, I’m also saying that I put a hard part of my existence into it. Like the iceberg, it stays beneath the surface, but it is all part of the whole work. Although it is not about my life, my art has to be from my life—I can’t ask someone else to do my concept, it has to be me doing it.

If I’m working or not working, you have to think about the work in both these ways to make it complete. I’m both wasting time and working very hard, it’s a Catch-22. Whether I stay in “art time” or “life time”, I am passing time. My art is doing time. I have lived for 50 years in New York but I don’t call New York home, I call New York “the best cage”. I’m alienated from the city, yet the city still embraces this alienation.

Rope Piece (1983-84) saw Hsieh attached to fellow artist Linda Montano for a year without touching each other Photo: Tehching Hsieh and Linda Montano, Life Images; courtesy Dia Art Foundation

How did you decide the format for each work? What dictated the progression from a year living in a cage to finally spending 13 years making art completely in private?

All the pieces consumed my life, but each in a different way. Cage Piece confined me physically; in Outdoor Piece there was always the possibility of violence—both artificial and natural. In Rope Piece I was exposed to another person, with no escape, but also not able to touch, so there was both intimacy and distance—it was often very difficult for both of us. Then in No Art Piece and the Thirteen Year Plan there was no outside energy from an audience. I had to be my own generator. All these consumed my life intensely and some still continue to affect me. My work was different each time but what counts is the repetition. Each piece was life from a different angle, a different perspective or point of view. But it all comes from the same idea that life is a life sentence, it is about passing time. When life is reduced to its minimum then time emerges.

At the end of Thirteen Year Plan, in a ceremony at New York’s Judson Memorial Church on 1 January 2000, you revealed a collaged poster that read, “I kept myself alive”. Why was this your last work of art (which you don’t even call art but instead, a concept)? Are you now an artist who does not make art?

No Art and the Thirteen Year Plan are artworks, but I don’t make art since 2000—and I don’t call myself artist after that. But if you want to call me an artist, that’s OK. It was better that in my last two pieces there was no art, instead of continuing to do one-year performances with no good ideas. In those last two works, art went back into life. Now I am like a lion: when he is not hunting, he is sleeping. Now that I am not hunting art, I am sleeping. Doing art or not, I am passing time. If a person is still alive and passing time, then the passing time itself has value. Like Waiting for Godot, about the one who will never come—the value is that you are still there waiting.

Biography

Born: 1950 Nanzhou, Taiwan

Lives: New York

Education: 1967 dropped out of high school

Key Shows: 2009 MoMA, New York; Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York; 2017 Taiwanese Pavilion, Venice Biennale; 2017 Tate Modern, London;

2023 Neue Nationalgalerie, Berlin

No gallery representation

• Tehching Hsieh: Lifeworks 1978-99, Dia Beacon, New York State, until 2027