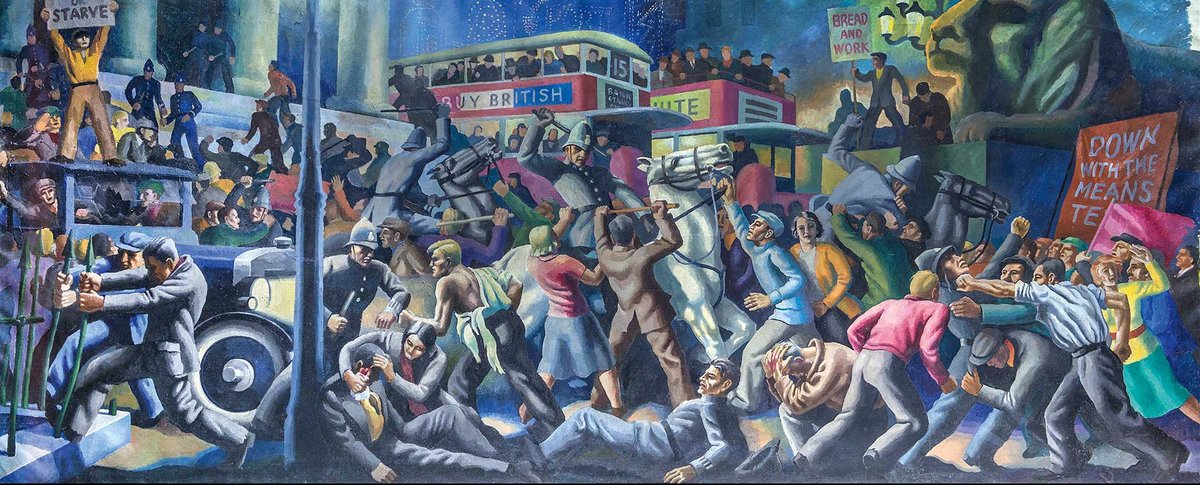

A chaotic scene of protesters clashing with police in London’s Trafalgar Square graces the dust jacket of this book. Demonstrators are shown being clubbed to the ground as railings are torn up for weapons and an officer on a rearing white horse prepares to strike. Painted by Cliff Rowe while he was staying in Soviet Russia, the monumental social realist canvas captures with vivid dynamism the civil unrest sparked in 1932 by the British government’s sweeping benefit cuts.

It was against a backdrop of economic hardship, unemployment, class struggle and rising political extremism that Rowe, having returned to London in 1933, became instrumental in establishing the Artists International Association (AIA)—a radical union of artists, which grew to become a popular front against fascism and war, and whose first decade the author and curator Andy Friend chronicles here with scholarly rigour and narrative verve.

The extent to which members were involved internationally is striking

Just a dozen or so men and women, mostly underemployed commercial artists associated with the Communist Party, attended the AIA’s first candle-lit meeting. Among them were Misha Black, James Boswell, James Lucas, James Fitton and Pearl Binder who, like Rowe, had spent time in Russia. Binder recounted enthusiastically how, in Soviet society, artists were supported, organised and suitably employed, sometimes sponsored by trade unions or the Red Army. To that small group, it all seemed a world away from the precarious situation in which many British artists now found themselves, in the wake of the Wall Street crash and ensuing global downturn. The capitalist system appeared to be faltering, while the political situation was becoming unbearable—oppressive at home, and increasingly dangerous internationally. As Friend writes, the goal of those who established the AIA (initially called the “Artists International”) was “to serve shared political goals through their art and to develop an artists’ organisation that would act as an auxiliary to progressive causes”.

Born from a belief in the power of art to revolutionise society, the AIA’s stated aim was “the International unity of artists against Imperialist War, War on the Soviet Union, Fascism and Colonial Oppression”. As Black later remarked, it “had no intellectual basis…it was purely socially and politically motivated [and] sprang from a real feeling of social responsibility”. The group, whose membership grew rapidly, designed posters, contributed to left-wing political publications, hosted public meetings and lectures and, most significantly, organised regular exhibitions, often on an ambitious scale. Their work is generously illustrated throughout Comrades in Art, from eye-catching political graphics and line-drawn cartoons to abstraction, realism and Surrealism. Although the AIA engaged with capital “P” politics, it evidently eschewed the art world’s aesthetic antagonisms by accommodating most styles of the period.

Powerful force

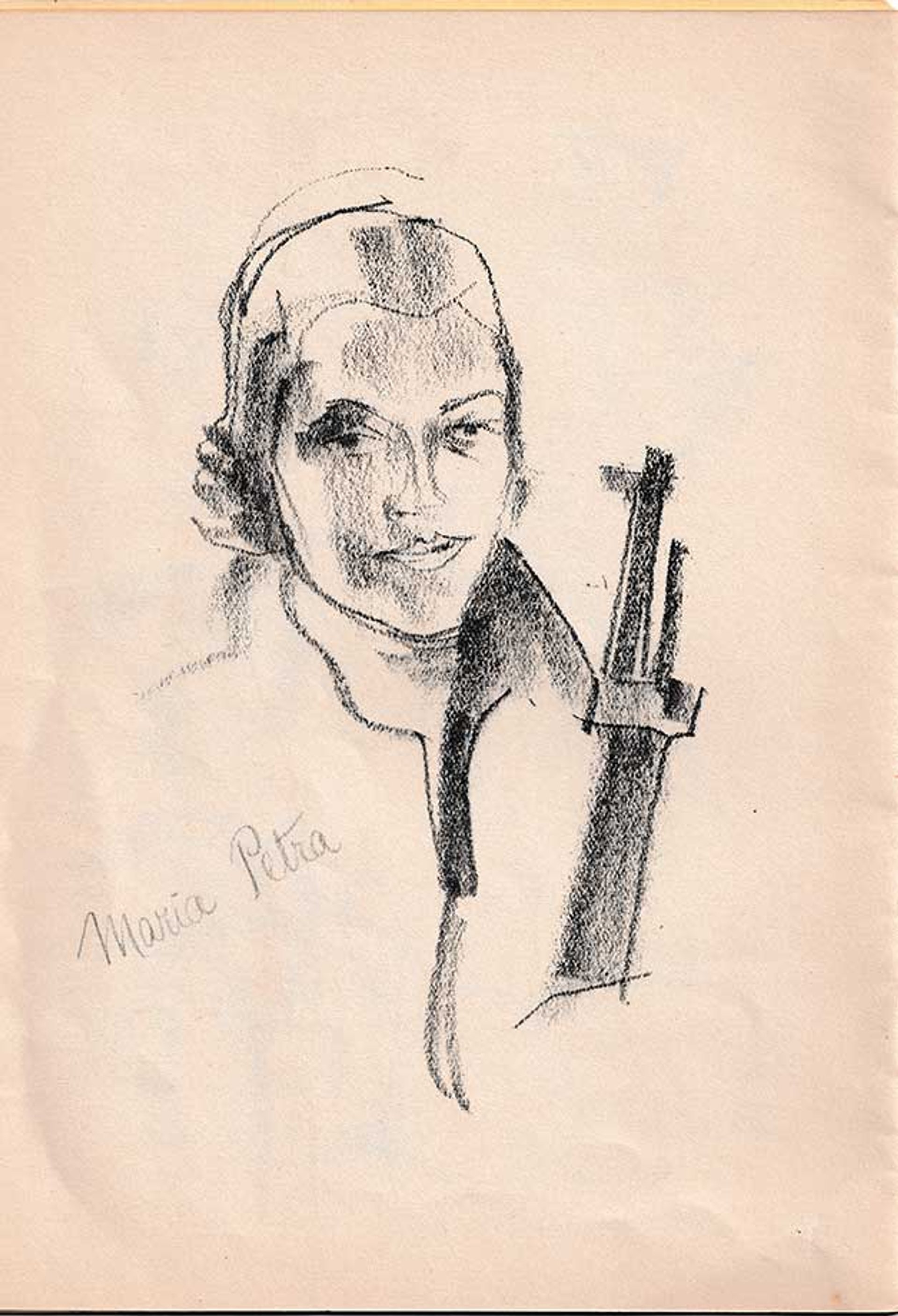

Under Black’s chairmanship, and with the well-connected sculptor Betty Rea as its secretary, the AIA became, in Friend’s assessment, “brilliant at networking and showed great ingenuity in pursuit of collective endeavour”. Indeed, despite being run by a nucleus of left-wing activists—several of whom were under British Security Service surveillance—it would soon include many of the country’s leading artists, such as Henry Moore, Paul Nash, Augustus John and Laura Knight. By the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in 1936, it had more than 600 members (eventually rising to just over 1,000) and could no longer be dismissed as a mere Communist Party front. Wisely, Friend does not dwell on its celebrities, focusing instead on the biographies of lesser-known figures such as Felicia Browne, who volunteered to fight with the communist militia in Spain and became the first British—and only female—combatant to be killed in action in that conflict.

The extent to which AIA members were involved internationally is striking. Friend uncovers multiple connections with Moscow, Paris, Barcelona and New York, showing how the organisation’s aims and activities were shared by equivalent groups, including the American Artists’ Congress, which similarly sought to resist global fascism and campaign for cultural freedom and democracy. Coinciding with the Italian fascist invasion of Abyssinia in 1935, the AIA’s pivotal exhibition Artists Against Fascism and War featured French, Dutch, Polish and Soviet rooms, while other well-attended exhibitions attracted international submissions from luminaries such as Fernand Léger, Joan Miró and Pablo Picasso, the latter welcoming AIA members to his Paris studio to view the powerful anti-war painting Guernica (1937) while it was still in progress.

As the Second World War approached, the AIA’s activities continued at pace, including the establishment of an Artists’ Refugee Committee to provide visas and homes for émigrés fleeing Nazi and fascist oppression. Regular exhibitions and events continued throughout the conflict and several small touring shows circulated to factory canteens, local authority-run British Restaurants and government offices. An affordable “Everyman Prints” series was also produced, fulfilling the AIA’s goal of extending public access to the arts. Its high-profile 1943 exhibition For Liberty is discussed at length by Friend. Held in the bombed-out basement of the John Lewis department store on Oxford Street, it featured 175 works, including Oskar Kokoschka’s crushing denunciation of warfare What We Are Fighting For (1943) and a section devoted to the “Four Freedoms” articulated by US President Franklin D. Roosevelt: freedom of speech and religion and freedom from fear and want.

Dynamic interplay

The story of the AIA was first told in 1983 by the Museum of Modern Art, Oxford, in the exhibition AIA: The Story of the Artists International Association 1933-1953. Expanding on this foundation, Friend’s study draws on numerous recently discovered sources, shedding new light on the AIA’s evolution from radical left-wing group to an organisation largely accepted by the British establishment. As a group biography, its richly detailed narrative deftly balances a range of individual stories without losing sight of the broader historical context. It shows how the dynamic interplay between art, politics and activism worked to support progressive agendas and influence public opinion during a period of extreme turmoil.

A Republican militia fighter by Felicia Browne, a member of the Artists International Association who was the first British, and the only female, combatant killed in action during the Spanish Civil War

Courtesy Thames & Hudson

But this is not a comprehensive account of the AIA, which continued until 1971, by then a shadow if its former self. In focusing on the first ten years—undoubtedly its most active and politically vital—much is omitted. We do not, for instance, read of its members’ involvement with the Festival of Britain, or their contributions to the post-war peace movement. Nor do we learn how it became politically emasculated in 1953 when the “Political Clause” was dropped from its constitution. Nevertheless, Friend has made a significant contribution to our knowledge of the group’s heyday, advancing our understanding and appreciation of its remarkable and far-reaching impact. With, in 2025, the looming spectre of fascism propelled by rising authoritarianism and far-right populism around the world, his revelatory study feels timely. Surely there is much to learn from the AIA’s example.

• Andy Friend, Comrades in Art: Artists Against Fascism 1933-1943, Thames & Hudson, 360pp, 202 illustrations, £40 (hb), published 4 September

• David Trigg is an independent writer, critic and art historian. He is the author of Art Books for the People: The Origins of The Penguin Modern Painters (Cambridge University Press, 2025)