From Munich to Hong Kong, this year has been crowded with centennial tributes to Robert Rauschenberg (1925-2008), whom the critic Robert Hughes described in 2006 as “the most important American artist of the last century”. Even with this global influence, Florida remained the artist’s centre of gravity for four decades, as materials and collaborators from the Sunshine State powered many of his breakthroughs—from his experiments with cardboard and scrap metal to the Rauschenberg Overseas Cultural Interchange (Roci), a seven-year programme that positioned art as cultural diplomacy at the tail end of the Cold War.

As Miami Art Week again convenes the art world in Florida, Rauschenberg’s presence in the state both widens and narrows. Beyond the presence of his work on the stands of Gladstone Gallery and Thaddaeus Ropac at Art Basel Miami Beach, two projects here mark the moment. Robert Rauschenberg: Real Time at NSU Art Museum Fort Lauderdale (until 26 April 2026) is one of the artist’s final centennial exhibitions, while the book Out of the Real World: Robert Rauschenberg at USF Graphicstudio will be published later this month to highlight the artist’s extensive collaboration with the Tampa print workshop.

Yet the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation announced this past summer that it would end its prestigious artist residency on Captiva Island and sell Rauschenberg’s home and studio there. Coming amid the year-long celebration of the artist’s legacy, this decision warrants a look back at how Rauschenberg’s Florida years shaped his ambitions and accomplishments.

Escape from New York

Born in Port Arthur, Texas, Rauschenberg led an itinerant early life. He pursued pharmacology at the University of Texas at Austin, served in the US Navy Hospital Corps in San Diego, then pivoted to art at the Kansas City Art Institute. His developing practice later took him to the Académie Julian in Paris and to Black Mountain College in North Carolina, where he met future collaborators including John Cage and Merce Cunningham.

Rauschenberg moved to New York in 1949 to study at the Art Students League and spent nearly two decades in Manhattan. His circle there included Cy Twombly, Susan Weil (his wife from 1950-52) and Jasper Johns, his one-time romantic partner.

No Wake Glut (1986) was part of a show of Rauschenberg’s Glut works—sculptures the artist created from scrap metal, such as old signs and car parts—at Thaddaeus Ropac gallery in Paris earlier this year Photo: Charles Duprat

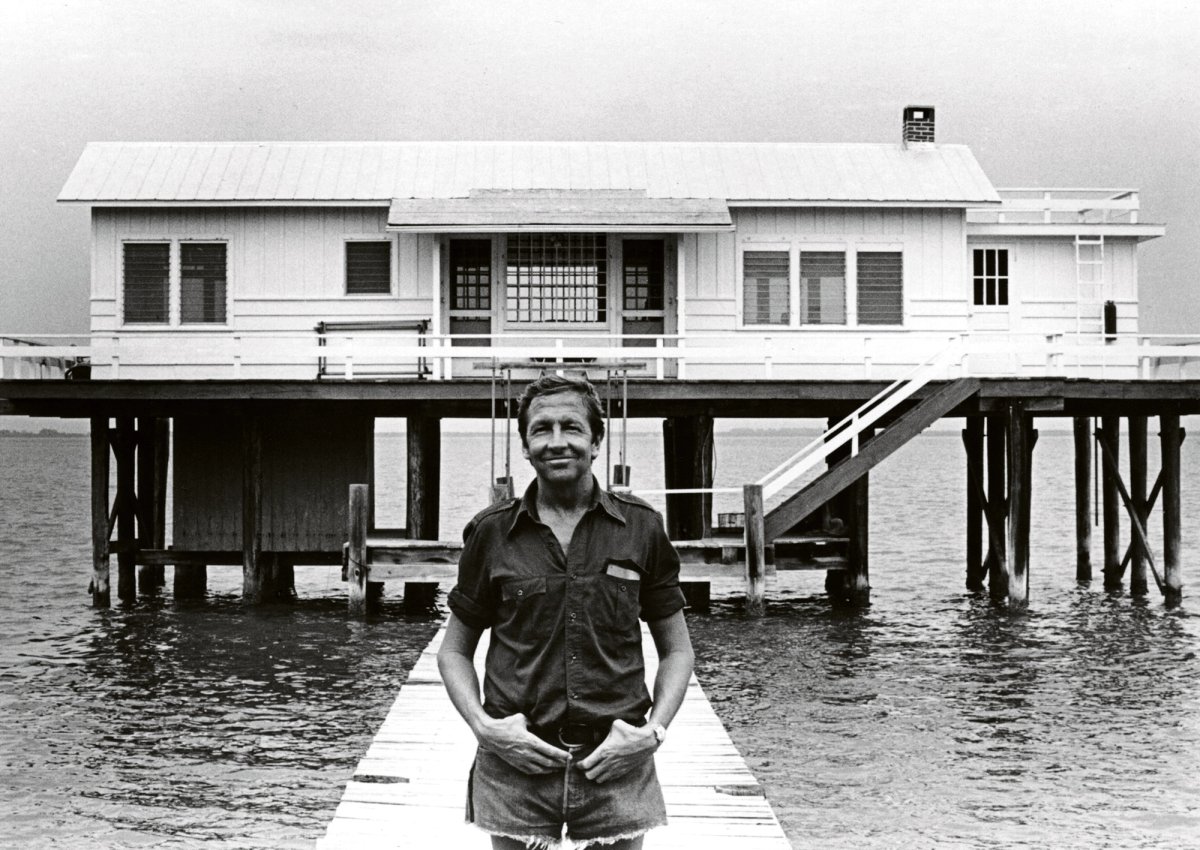

But in autumn 1960, frustrated with a lack of progress on his Dante drawings, Rauschenberg sought isolation on Treasure Island, off Florida’s west coast. By 1968, he had purchased property on Captiva, a barrier island further south. Although he maintained a Manhattan studio, Rauschenberg relocated to Captiva in 1970, eventually becoming its largest private landowner.

Rauschenberg’s shift to the island echoed a broader pattern of post-war artists seeking distance from the New York City grind: Agnes Martin left for New Mexico in 1967; Ellsworth Kelly settled in Spencertown, New York, in 1970; Johns established a base on the Caribbean island of St Martin in 1972; and Brice Marden developed a summer studio on Hydra, Greece, in the early 1970s.

For Rauschenberg, Captiva was both studio and subject. Describing the island as holding “a magic that was unexplainable in its power”, he wrote to the Orlando Sentinel critic Philip Bishop: “I have thanked my instinct every day I am here and when I can’t be, Captiva is the foundation of my life and my work.”

New materials, new visions

Courtney J. Martin, the executive director of the Rauschenberg Foundation, tells The Art Newspaper that “Florida served not only as his home but also as a catalyst for artistic innovation that continues to resonate globally.” One way to trace that innovation is through the materials that defined the artist’s Captiva years. They range from works on fabric (many on view at the Menil Collection in Houston until 1 March 2026) to his scrap-metal Glut sculptures, which Thaddaeus Ropac introduced to France via an exhibition at the gallery’s Paris space this autumn.

“Perhaps the most surprising aspect of Rauschenberg’s works from his first decade in Captiva is their beauty,” say the organisers of his show at NSU Art Museum—the museum’s director and chief curator, Bonnie Clearwater, and the curator Ariella Wolens. “Even when using the lowliest of materials, such as the cardboard boxes that formed his first series of new work begun in Captiva in 1971, he distilled their alluring beauty and elevated their position as art.”

Graphicstudio emerged as a crucial partner in this era. Mark Fredricks, the editor of Out of the Real World and a researcher at the printshop, says the collaboration “took place over two main phases, 1972-74 and 1983-87”,

and proved prolific. The first two years alone yielded 22 mixed-media prints and five sculptural editions. Among them—and on view at NSU Art Museum—is Switchboard (Airport Suite) (1974), Graphicstudio’s first project primarily realised off-site, partly by shipping an etching press to Rauschenberg on Captiva. The title nods to the artist’s peripatetic schedule; the editions, made entirely on fabric supports, were signed in a Tampa airport hotel room. Clearwater and Wolens describe the works as “gossamer-like”, fluttering in an “unchoreographed dance stirred by the viewer’s own movement”.

Out of the Real World also underscores the wide-ranging collaboration between Rauschenberg and Graphicstudio’s founder, Donald Saff, who met the artist in Greenwich Village in the 1960s. In addition to his role in editioning, Saff served as the artistic director of Roci (named for Rauschenberg’s pet turtle, Rocky), an initiative largely funded by the artist and combining cultural diplomacy, workshops and a travelling exhibition.

Roci toured ten countries that Rauschenberg identified as “sensitive”, from East Germany to Venezuela. He added new, site-responsive works at each stop alongside the pieces shown in previous venues. “Roci is, in effect, Rauschenberg’s way of acting personally on behalf of concepts as global and daunting as peace and understanding,” Saff said in 1991.

Serving as a key liaison, Saff convened local artists, writers and poets for catalogues tailored to each site, bringing the world into dialogue with Rauschenberg’s Florida studio and sending Captiva’s ethos of experimentation across the globe.

Rauschenberg’s legacy

Rauschenberg’s collaboration-rich Florida years and its setting reshaped how later artists worked with materials, site and community. The Rauschenberg Foundation converted most of the Captiva estate into a residency in 2012, and more than 500 artists of all kinds have since passed through—including Kevin Beasley, Douglas Coupland, LaToya Ruby Frazier, Senga Nengudi and Jennie C. Jones.

“Captiva was different from other residencies in many ways,” says Jones, a 2014 resident. “Bob’s legacy was tangible; the place was filled with the gravity of his footprint on the world.” During her residency, Jones made a series of works on paper that she describes as “thinking pieces”.

“That kind of experimentation can feel vulnerable, but Captiva felt safe,” Jones says. “That spirit of doing felt profoundly connected to Bob himself.”

She remembers the campus as “a magical but fragile environment”, and Captiva’s environmental precarity has become insurmountable in the decade since. In 2021, Kendall Baldwin of WXY Architecture, who had worked on the campus since 2016, described Captiva to the Santiva Chronicle as “tremendously vulnerable”, but noted that “the foundation is working with climate change, not against climate change”. Damage from recent storms—Hurricane Ian in 2022 and Hurricane Milton in 2024—has wrought further challenges to the estate. The formal announcement to close and sell the 22-acre property came in August 2025; the foundation’s statement cites the “recurring storm damage, broader climate risks and rising maintenance costs” as its prime reasons.

“It’s not easy to process the foundation’s decision because of the powerful legacy and experience myself and others had there,” Jones says. “But climate change is all too real. It’s affecting everything—including Captiva.”

Proceeds from the sale, together with funds previously earmarked for the campus’s upkeep, will likely be redeployed to more flexible forms of artist support. In this way, even the selling of Rauschenberg’s compound will advance the legacy of the island and the artist who called it home.