Over the past decade, the London-based multimedia artist and film-maker Lawrence Lek has evolved a cinematic universe that challenges the notion of immersive experience as senseless spectacle, replacing it with a critical inquiry into the posthuman condition. Back in 2023, he introduced audiences to the fictional world of NOX (“nonhuman excellence”), where self-driving cars are rehabilitated at a centre for non-compliant machines.

A mark of Lek’s global reach, as well as the allure of his Smart City series (which includes NOX), this year he has performed NOX (Live) in the Tanks at Tate Modern; exhibited a new installation, NOX High-Rise, at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles; and held a survey show at Goldsmiths Centre for Contemporary Art (CCA) in London, Life Before Automation (until 14 December). As his latest work, NOX Pavilion, goes on show at the Bass Museum of Art in Miami Beach, Lek discusses the capacity of video games to “reworld” reality by putting audiences in the driver’s seat.

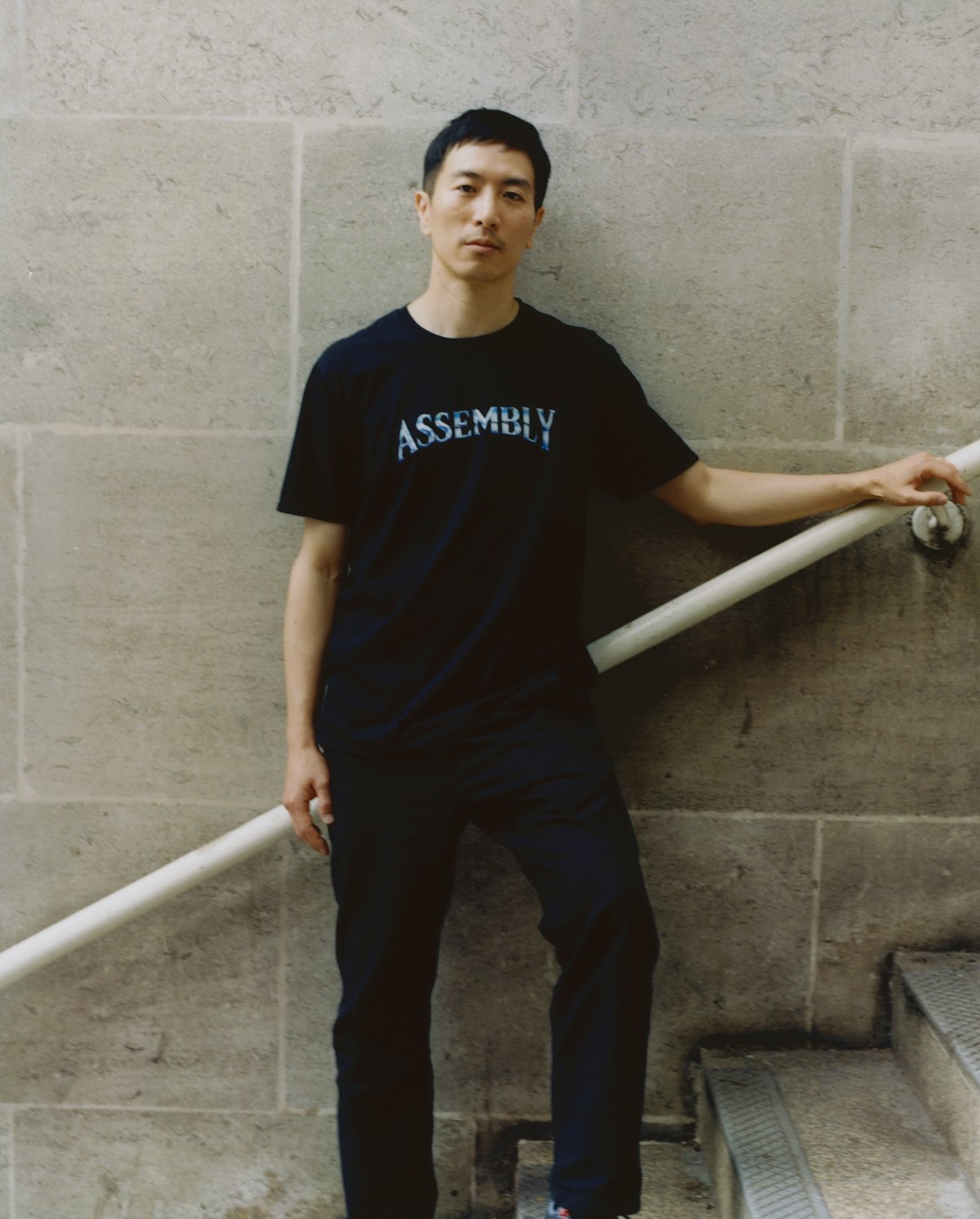

A still from Lek’s installation NOX, in which he envisages a project to rehabilitate self-driving cars that have gone rogue. A new iteration of the work is on show at the Bass Museum during Miami Art Week

Courtesy of the artist and Sadie Coles HQ

The Art Newspaper: Is there an intention behind having multiple variations and sites of delivery for the same work?

Lawrence Lek: I work intuitively, so moving between architecture, video, gaming and music has evolved organically. I’ve realised that my practice is really about different forms of immersion, which is a word that gets thrown around a lot. I think of immersion as a state of perception—the point at which you forget that you are fully within the medium. The performance at the Tate Tanks was about the immersion in the present moment that you get with music. With that show, I played NOX as a real-time video game, a new form of expanded cinema.

The narrative of my practice is like a continuously expanding universe, so each staging, exhibition or performance is a portal into an increasingly complex world. Since Goldsmiths CCA was a survey show, I wanted to situate NOX as a science-fiction of the near future, placed within my larger “worldbuilding”, that frames automation as a centuries-spanning project across human civilisation.

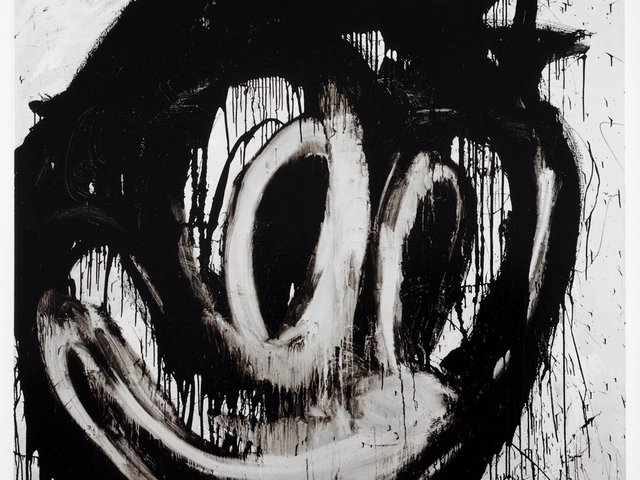

An installation view of the first edition of Lek’s fictional world NOX at LAS Art Foundation, Berlin

Courtesy of the artist and Sadie Coles HQ

A still from NOX Pavilion, at the Bass, which introduces new elements to the immersive work

Courtesy of the artist and Sadie Coles HQ

How does your new NOX Pavilion at the Bass expand on the fictional world of NOX?

NOX is a world centred on a rehabilitation programme for disobedient self-driving cars. Think of it like a real-life video game. Each edition of NOX is like an expansion pack from the original “release”. In its original manifestation at LAS Art Foundation in Berlin, NOX was a takeover of a three-storey building, and the different levels corresponded to a highway, a rehab clinic and a gaming surveillance zone, in a crude replica of the Freudian construct of the id-ego-superego as it might relate to a self-driving car in crisis. At the Hammer Museum earlier this year, NOX High-Rise expanded this with an installation for an anonymous apartment for a corporate artificial intelligence (AI) engineer.

With NOX Pavilion at the Bass, I was reflecting on the world of Miami Beach, not literally, but as a liminal setting on the edge of Florida. The structure of a half-built pavilion is present in both the physical exhibition space and in a new video commissioned for an LED wall, where a crash-test dummy promotes the AI parent company’s interests. I think of the pavilion as the ultimate functionless archetype—a structure that exists as an icon and as a framework that also reflects Miami Beach’s vernacular style. Each iteration of NOX is a reflection on the place where it is made and on the idea of architecture as a space in between the real and the imagined.

The new exhibition allows visitors to step into the role of a trainee therapist. What prompted that decision to extend NOX into a participatory experience?

In the original exhibition in Berlin, audiences wore headphones that tracked their locations in space so that when they entered new areas, new sounds and voiceover would play. The physical experience drew from the language of an open-world game. The idea is that when you arrive on the top floor, your role changes from being a spectator or owner of a traumatised self-driving car to being a trainee therapist who must fix broken cars. Of course, I’m interested in the idea of role-playing games where a player changes their identity. I find that the transmutation of subjectivity is one of the fundamental experiences of immersive art. I’m also interested in the boundaries of this interaction, finding subtle ways to make the audience ask themselves: are we playing or are we being played? There’s a line from NOX where the self-driving car, Enigma-76, reflects on their ancestors: “What a strange fate they had—not to drive, but to be driven.”

Since I first encountered your work through the film Geomancer in 2017, it feels like the world has grown ever closer to the kind of corporatised state of human-nonhuman relations and transactions that you envisaged back then. Are you conscious of this prophetic quality to your work?

I once had a teacher, whose designs were stolen by a Hollywood studio for a sci-fi film, who said that you had to be a near-seer and a far-seer at once. The near-seer looks at the danger on the horizon, but the far-seer looks at the possibilities. In Geomancer, which is set in the year 2065, I named the fictional AI company Farsight. Later, I gave that name to my own studio, as if I’d stepped into the world and become a character myself. In a way, I’m just living out a prophecy that began inside the work itself.

- Lawrence Lek: NOX Pavilion, the Bass Museum of Art, until 26 April 2026