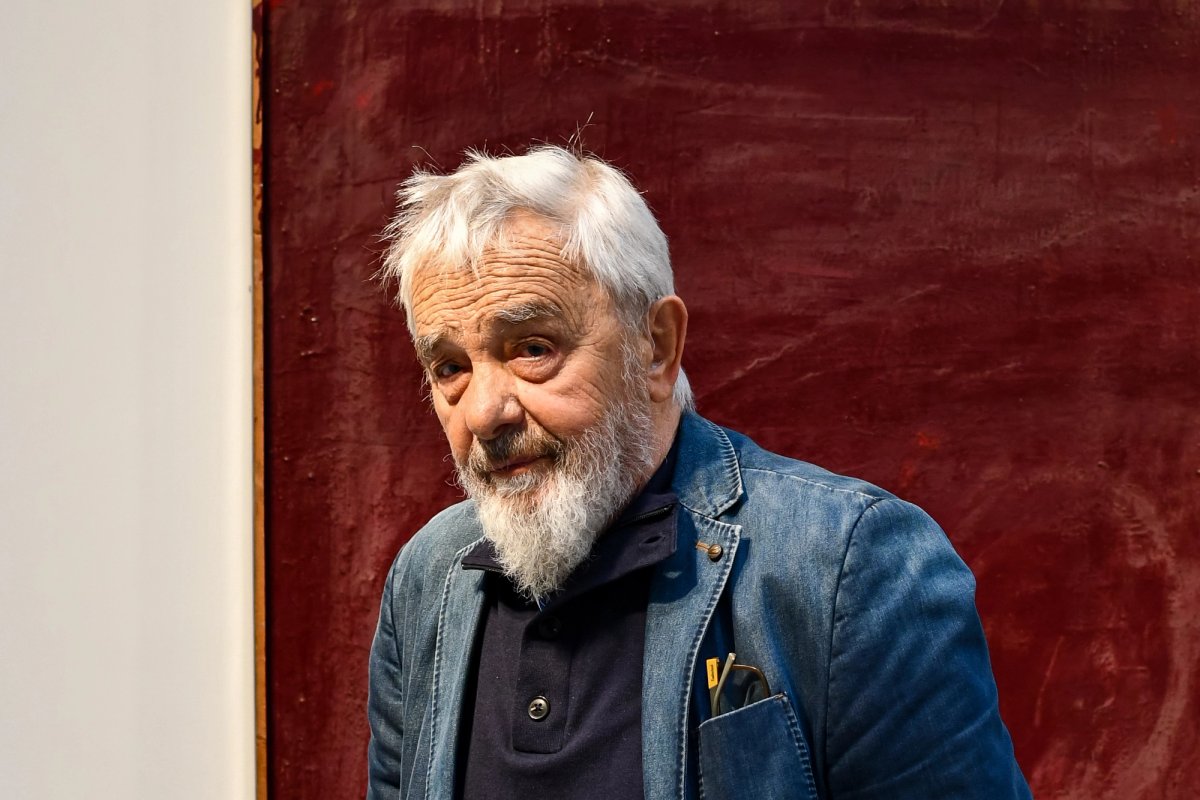

Arnulf Rainer, a leading figure of the Austrian avant-garde whose gestural paintings confronted the atrocities of the Holocaust and Hiroshima and whose unflinching approach to experimental self-portraiture made him instantly recognisable, has died aged 96; his death on 18 December was confirmed by his gallery Thaddaeus Ropac who described him as one of the most influential artists of the post-war period.

Born in 1929 in Baden, Austria, Rainer came of age in the aftermath of World War II as a restless enfant terrible who distanced himself from academic traditions, finding early kinship with Surrealism and Art Informel. Largely self-taught, Rainer gravitated to Vienna in the late 1940s, a city where daily life unfolded amid rubble, scarcity, and the lingering trauma of war.

In this environment, Rainer’s practice thrived as he became a crucial figure in the reawakening of Austrian contemporary art. He was one of the founding members of Galerie nächst St Stephan, one of the very few galleries in postwar Vienna which offered a vital meeting point for artists seeking alternatives to a conservative art world playing safe and desperately seeking commercial viability.

Galerie nächst St Stephan would go on to shape generations of Austrian art, serving as the launchpad for many of the country’s most significant figures, including Maria Lassnig. Rainer’s presence there was formative: his radical approach to painting, rejection of polished surfaces, and insistence on psychological intensity helped define the gallery’s ethos. In Vienna, Rainer forged a community that was small but intellectually ferocious, united by the belief that art must square up to the material circumstances of historical traumas rather than merely apologise for them.

By the early 1950s, he had begun producing the works that would define his legacy. In his Übermalungen (overpaintings), Rainer featured painted over photographs, self-portraits, crosses, faces, and even reproductions of historical works, overlaying them with aggressive gestures, dense black strokes, scratches, and erasures that both concealed and intensified the images beneath to create a charged atmosphere in which the human form is transformed, often by a satirical grotesquerie, and comes close to being obliterated altogether. In these works, violence and vulnerability coexist; the surface becomes a record of psychic struggle, weighed down with the heaviness of historical inheritance.

In 1951, he produced a portfolio of photographs, Perspectives of Destruction, that referenced 20th-century tragedies such as Hiroshima and the Holocaust. One of his most arresting mid-career paintings, Hiroshima (1982), which addressed its subject through gesture, erasure, and violent mark-making, whereby the canvas itself appears scarred, demonstrated the impossibility of adequate representation of one of the century’s defining catastrophes.

His frequent use of his own image, distorted, masked, or partially erased, turned the self-portrait into a site of existential inquiry rather than self-celebration. “For him, as Rainer once said, art history is not a history in which one style replaces another”, said the Dutch curator Rudi H. Fuchs. “For him, art has a cumulative quality; what he has painted remains part of his knowledge... An artist appropriates the past and adds something new to it.”

Throughout his career, Rainer resisted easy categorisation. Though associated at various times with Art Brut, Abstract Expressionism, and Viennese Actionism, he remained fiercely independent, sceptical of movements and labels alike. This resistance extended to his public persona: reclusive, austere, and often critical of the art world, he nevertheless achieved international recognition.

His work entered major museum collections across Europe and the United States, including the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the Art Institute of Chicago, and he represented Austria twice at the Venice Biennale (first in 1978, the year that he received the Grand Austrian State Prize, and then again in 1980), cementing his status as a central figure in postwar art.

Rainer’s importance lies not only in institutional accolades, but in the enduring urgency of his work. Rainer insisted that art confront discomfort, fear, and mortality, rather than soothe or distract, despite claiming that “the principles of my works… are the extinction of expression, permanent covering and contemplative tranquillity.” He is survived by his wife Hannelore, his daughter Clara, and his son-in-law Javier.

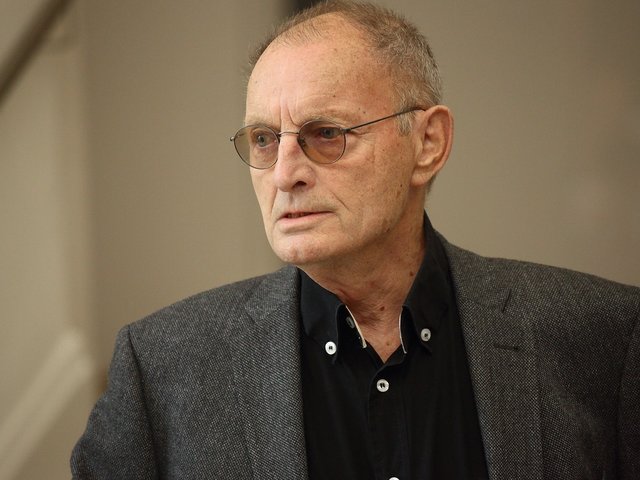

Ulrich Rainer, Ohne Titel, around 1989

Photo: Ulrich Ghezzi