Cezanne

Fondation Beyeler, Basel, 25 January-25 May

Paul Cezanne (1839-1906) represented a powerful inspiration for the artists who came after him; as Pablo Picasso famously put it, he was “the father of us all”. Now, an ambitious exhibition focusing on the French artist’s later works, when he was at the height of his powers, will open at Basel’s Fondation Beyeler in January.

The show, simply titled Cezanne and coming 120 years after the artist’s death, will follow a major exhibition held in 2025 in Aix-en-Provence, the city where he lived for most of his life. That collection of works concentrated on pieces painted on his parents’ estate at the Jas de Bouffan from 1860 onwards. So although there is some overlap, the Beyeler is concentrating on the artist’s later years, when he worked at his Atelier des Lauves, just outside the centre of Aix. It was near there that Cezanne could see his favourite motif, the view towards Mont Sainte-Victoire.

Paul Cezanne’s Pommes et oranges (around 1899) is one of the paintings that will show at his self-titled exhibition at Basel’s Fondation Beyeler from

25 January to 25 May © Grand Palais RMN (Musée D’Orsay) / Hervé Lewandowski

The Swiss museum will have around 60 oil paintings and 20 watercolours. What makes the exhibition particularly special is that half the works come from private collections, and so many are rarely on view.

Among the surprises will be a privately owned oil study of The Bathers (around 1902-06), which was sold at Christie’s in 2011 for €2.3m. Along with many of Cezanne’s late works, it might appear unfinished, with the figures only lightly blocked in. As the curator Ulf Küster points out, Cezanne’s late paintings tend to be fragmentary, so the “unpainted surface becomes a kind of projection surface” for the viewer to fill in themselves—and become involved with the picture.

Another key painting will be the earlier The Boy in the Red Vest (1888-90), on loan from the E. G. Bührle Collection at the Kunsthaus in Zurich. The boy’s right arm is too long, his right ear much too big. When Cezanne was interested in a detail, he simply enlarged it. The effect works, capturing the personality of a melancholic adolescent.

A key strand in the Beyeler’s presentation will be examining Cezanne’s radical take on perspective and the way he painted his own very personal way of seeing. The exhibition will also emphasise how he broke away from Impressionism, becoming a major figure in the creation of 20th-century Modernism. M.B.

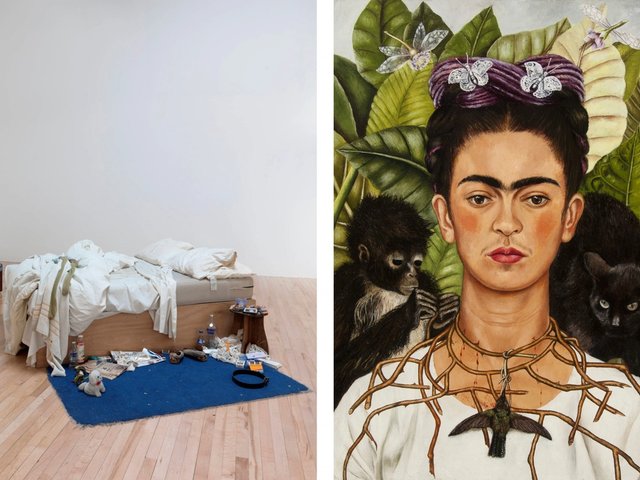

Left: Augustus Marshall’s Portrait of Edmonia Lewis (around 1870), which is in the collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture; right: Edmonia Lewis’s Bust of Robert Gould Shaw (1864) Left: Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, 2020.10.5; right: Collection of the Massachusetts National Guard Museum and Archives, photo: Stephen Petegorsky.

Edmonia Lewis: Said in Stone

Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, 14 February-7 June

Georgia Museum of Art, 8 August-3 January 2027

North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh, dates TBC

When the Georgia Museum of Art acquired a marble work by the 19th-century American artist Edmonia Lewis back in 2016, two of the museum’s curators decided it was high time someone organised a proper exhibition for the sculptor. Her name was very much in the air and gaining increased recognition as one of the first internationally acclaimed Black and Indigenous woman artists, but few had taken on the laborious task of tracking down all her known works and scouring the archives.

Nearly a decade in the making, the travelling exhibition Edmonia Lewis: Said in Stone will feature 30 sculptures by the artist and provide a comprehensive survey of her entire career. The exhibition will premiere at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem before showing at the Georgia Museum of Art and the North Carolina Museum of Art, and will include works by her contemporaries and generations of artists that she inspired.

The exhibition and its accompanying scholarly catalogue will feature never-before-shown sculptures and new archival discoveries. Lewis’s early-career plaster bust of Colonel Robert Gould Shaw (who was the leader of the all-Black Massachusetts 54th Regiment) was deemed lost after she debuted it in Boston in 1864, but it will be included in the exhibition. Another plaster portrait going on display of the abolitionist John Brown has not been publicly shown since the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia. Other discoveries include previously unpublished letters, her works on less familiar subjects and a vintage photograph of Lewis’s first publicly exhibited portrait: a sculpture of Sergeant William Carney (another member of the 54th Regiment). The whereabouts of the Carney sculpture remains unknown, however.

“While Lewis found fame in her lifetime, several of her prized sculptures remain lost. Written accounts in her own words are scarce,” says the Peabody Essex Museum’s curator Jeffrey Richmond-Moll, who co-curated the exhibition together with the Georgia Museum of Art’s Shawnya Harris. “This exhibition represents an ongoing project of recovery—of piecing together fragments and listening for further details when the record appears silent.” K.C.

Portrait of a Lady with a Unicorn (1505-6) is one of the paintings featured in the landmark exhibition Raphael: Sublime Poetry at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York from March © Galleria Borghese, photo: Mauro Coen

Raphael: Sublime Poetry

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 29 March-28 June

Raphael—like his slightly older contemporary and erstwhile rival, Michelangelo—may only need one name, but does he have what it takes to make a blockbuster? That is what the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York will find out this early spring, when it mounts a full and fabulous survey of the High Renaissance artist ne plus ultra. Raphael: Sublime Poetry has been in the planning for seven years and will feature almost 240 works, including more than 30 Raphael paintings and around 170 drawings, works by his celebrated assistants, including Giulio Romano, and pieces by his peers such as Luca Signorelli and Pinturicchio. Loans will include The Alba Madonna (around 1509-11), which embodies the perfected ideals of the early 16th century, from the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC. The Met will display it along with its studies, borrowed from the Palais des Beaux Arts in Lille.

The show will be the first true Raphael survey the US has even seen, according to the museum

One whole gallery devoted to Raphael’s portraits will be top-heavy with A-list arrivals, including Portrait of a Lady with a Unicorn (1505-6) from the Galleria Borghese in Rome; the pale-skinned La Muta (around 1503-05) from the Galleria Nazionale delle Marche in Urbino, the artist’s birthplace; and Portrait of Baldassarre Castiglione (1514-15) from the Musée du Louvre in Paris. Also arriving from Rome: La Fornarina (1518-19), a celebrated and mysterious nude that some people think might be Raphael’s lover and others regard

as a sex worker.

The exhibition is being curated by the Met’s curator of drawings and prints, Carmen C. Bambach, who describes it as the completion of a generation-long trilogy that started with the museum’s Leonardo da Vinci: Master Draftsman in 2003, followed by Michelangelo: Divine Draftsman and Designer in 2017. The show will also be the first true Raphael survey the US has ever seen, according to the museum.

The Head and Hands of Two Apostles (around 1519-20), coming from the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, is a ravishing cartoon related to The Transfiguration (1516-20), Raphael’s last and arguably greatest painting, now at the Vatican. Meanwhile, from his early career, the Colonna Altarpiece (around 1504-05) will be reconstructed with all its constituent parts for the first time, Bambach says, with panels from the UK and Boston joining the Met’s own holdings. J.S.M.

Marcel Duchamp’s infamous urinal, Fountain (1917), changed the art world, and will be on display with around 300 further pieces at the Museum of Modern Art in New York as part of the first survey of the French artist’s work in the US since 1973 Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia

Marcel Duchamp

Museum of Modern Art, New York, 12 April-22 August

When Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968) arrived in New York from Paris in 1915, he was met at the boat by Walter Pach and promptly taken to meet Walter and Louise Arensberg, ardent fans of the artist’s Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 (1912). “I stayed at his place for a month, during which our friendship was born, a friendship which lasted all my life,” Duchamp would tell an interviewer in 1966.

The Arensbergs bequeathed their unique comprehensive collection of Duchamps, among other artworks, to the Philadelphia Museum of Art (PMA) in 1950. Duchamp once described quite how much this meant to him: having his works scattered here and there would have felt like having a finger or a leg amputated, he said. The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) curator Ann Temkin points out that this is not something you expect “of this person who is seen to be so detached and ironic and cerebral, rather than, in any way, emotional or personal”.

Every generation has found newly relevant propositions in Duchamp’s work to tap into

Come April, Duchamp—that great contradictor—will take centre stage at MoMA in the first survey of his work in the US since 1973. A joint production between the PMA and MoMA, the show heralds no anniversary, but instead underscores, Temkin says, “the sense that we had of Duchamp’s importance continuing to increase, if anything, over this first quarter of the 21st century”.

It is, of course, a truism to say that Duchamp revolutionised what art could be. What this chronological showcase of around 300 works (a large show, by MoMA standards) aims to demonstrate is that every generation since has found newly relevant propositions to tap into. Until fairly recently, Rrose Sélavy, Duchamp’s female alter ego, was not the most magnetic aspect of his oeuvre. Now she looms large, as does his interrogation of the role of making, which also accrues only greater relevance in the face of the “massive questions around the role of human handiwork and technological reproduction we’re facing,” says MoMA curator Michelle Kuo.

Duchamp famously said it is the spectator who creates the work of art. But he also took infinite care over making and displaying objects—whether that was the artist’s infamous urinal, Fountain (1917), or his Mona Lisa with a moustache, L.H.O.O.Q. (1919)—that changed the world. “We’re giving his art back to the spectators,” Temkin says. D.B.S.

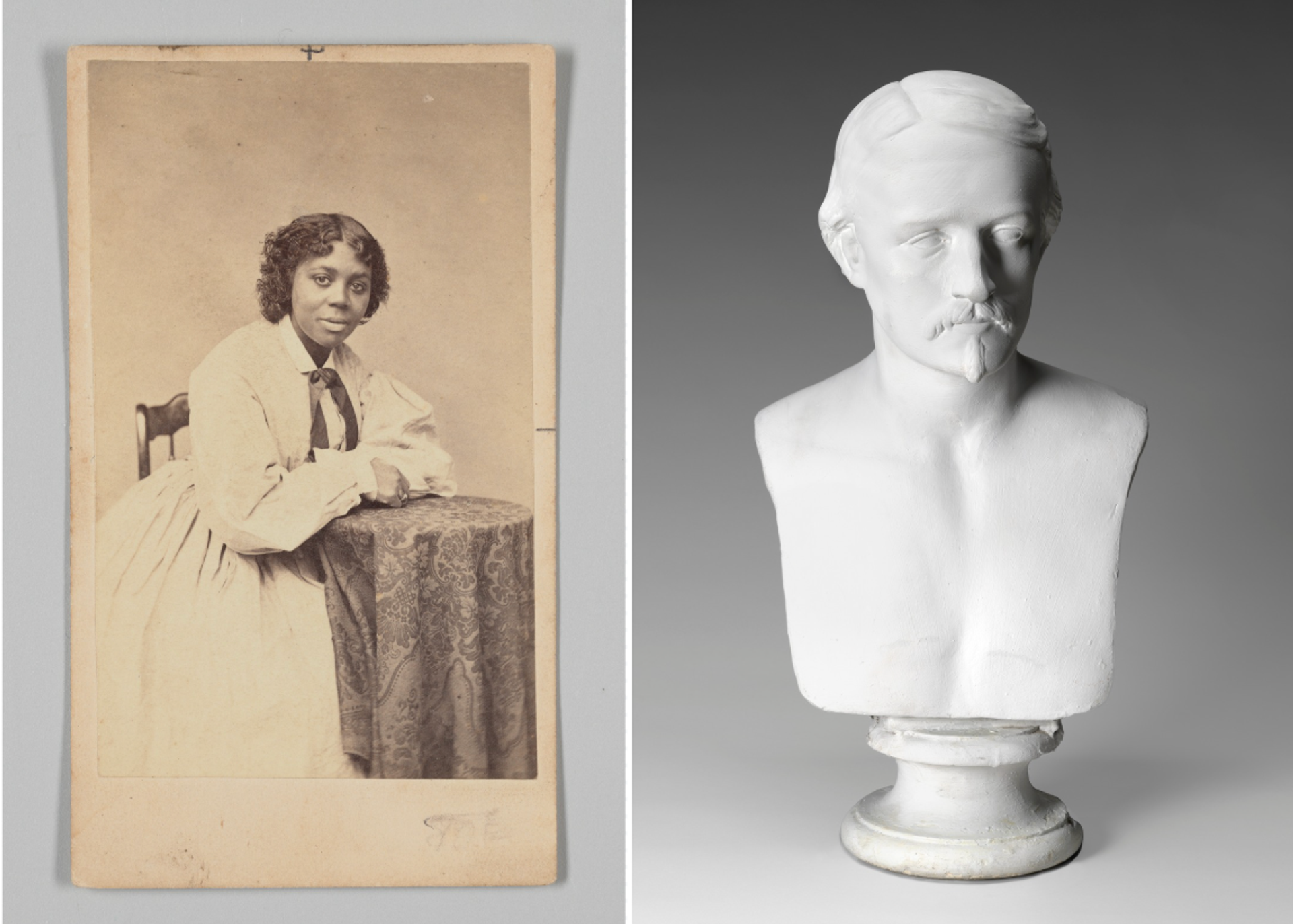

The Crucified Christ with a Painter (around 1650) by Francisco de Zurbarán is part of a touring exhibition that will begin at London's National Gallery on 2 May Museo Nacional del Prado

Zurbarán

National Gallery, London, 2 May-23 August 2026

Musée du Louvre, Paris, 7 October-25 January 2027

Art Institute of Chicago, 28 February 2027-20 June 2027

Francisco de Zurbarán is regarded as the arguably most austere artist of 17th-century Spain, which at its extreme was home to perhaps the severest form of the Baroque. His paintings of monks and saints balance a formal clarity and directness with a mood of solemn contemplation and transcendence. But a major exhibition, beginning in May at the National Gallery in London before touring to the Musée du Louvre and then the Art Institute of Chicago, will attempt to emphasise the humanity and tenderness alongside the monumentality.

“Yes, he’s austere, and yes, these figures feel almost sculptural,” says Francesca Whitlum-Cooper, the co-curator of the exhibition. “But then I would also say that this is someone whose ability to paint the stuff of this world is extraordinary.” Key to this palpable tactility is the fact that Zurbarán—born in 1598 in Extramadura, the harsh, westernmost region of Spain—was the son of a cloth merchant. For all the dramatic “almost Caravaggesque lighting”, Whitlum-Cooper says, he evidently “understands wool and brocade and how pleats fall and how trim hangs”.

Zurbarán made his name in his native region and then in Seville, with huge commissions from religious orders, comprising “22 pictures here, 15 pictures there”, Whitlum-Cooper says. The exhibition, which will feature more than 40 works, cannot reflect the full epic nature of these projects, but can explore “how he approaches narrative on that scale”.

The curator suggests that while Zurbarán is “painting these transcendental religious moments”, he is also “making them completely of our world. To me, that is the magic.” Agnus Dei (1635-40, Lamb of God), which will be coming on loan from the Museo del Prado in Madrid and is perhaps Zurbarán’s most famous picture, is emblematic of this duality. “You stand in front of that picture, and it is so pared back, so stark, so dark… but that fleece absolutely feels like you can put your fingers into it.”

The Prado is also lending the touring exhibition The Crucified Christ with a Painter (around 1650)—a relatively late self-portrait of the artist, palette in hand, as St Luke, beneath a cadaverous Christ on the Cross. This is the closest we get to Zurbarán the man, since there are no letters in which we “hear his voice”, Whitlum-Cooper says. “You look at that painter and the feeling in the figure and the way he’s looking up [to Christ] in that profile. And for me, that’s it: that’s Zurbarán talking to us.” B.L.

Anish Kapoor’s Mount Moriah at the Gate of the Ghetto (2022) is among the works on show at the artist’s retrospective at the Hayward Gallery in London from 16 June Photo: Attilio Maranzano. © Anish Kapoor. All rights reserved, DACS, 2025

Anish Kapoor

Hayward Gallery, London, 16 June-18 October 2026

As the Hayward Gallery director Ralph Rugoff reaches his final months in post, it is perhaps fitting that his last major exhibition is a large-scale survey of one of the UK’s most high-profile living artists, Anish Kapoor. This sweeping survey will offer a sight of the full range of Kapoor’s work, from his colossal, gallery-filling installations and sculptures of polished steel to blacker-than-black surfaces and blood-coloured impasto paintings that are suggestive of offal and viscera.

The highlight of the show will undoubtedly be two new as-yet-untitled installations, on a characteristically vast scale. One the gallery describes as “an inflated PVC membrane that fills the six-metre-high space, challenging our sense of scale and self” and the other “a dark mountainous threshold [that] looms down amid a sprawling red landscape”. A third large-scale work, titled Mount Moriah at the Gate of the Ghetto, is more of a known quantity. It’s a giant effusion of blood-coloured wax that was originally placed in the Palazzo Manfrin in 2022, the Venetian building that the artist has owned since 2018 and which houses the Kapoor Foundation.

This survey will offer the full range of Kapoor’s work, from colossal installations to blood-coloured impasto paintings

Rugoff says that there are no “specific external events” behind the decision to mount the show, but rather it is down to what he calls the Hayward Gallery’s “ongoing interest in this leading artist’s work, and our conviction that Kapoor has created several significant bodies of work since his last major London exhibition in 2009 at the Royal Academy”. The director also points out that the Hayward got there first, staging Kapoor’s first big London show in 1998.

Since those days, of course, Kapoor has gone on to become a celebrated household name. At one end of the scale scoring multiple public commissions—such as 2006’s Cloud Gate, better known as “the bean”, in Chicago or the gigantic Orbit tower constructed for the 2012 London Olympics—and at the other, creating deeply personal, not to say hermetic, works such as the paintings he showed at the Museum of Modern Art in Oxford in 2022.

As Rugoff adds: “With its inventive and provocative exploration of key concerns, such as the interplay between self and environment, the manipulation or unreliability of perception, and the fragility of our bodies, Kapoor’s art is more relevant than ever.” A.P.

Ana Mendieta's Imágen de Yágul, Mexico (1973) © The Estate of Ana Mendieta Collection, LLC. Licensed by DACS

Ana Mendieta

Tate Modern, London, 9 July-10 January 2027

In June 2016, as Tate Modern celebrated the opening of its Blavatnik extension, a group of protesters gathered outside, dressed in funereal black. “Where is Ana Mendieta?” one of their signs read. They were protesting the lack of representation of the late Cuban-American interdisciplinary artist at the museum, whose rehang included work by Carl Andre, her husband, who was charged with her murder in 1985 but subsequently acquitted.

In 2020, Tate Modern acquired six of Mendieta’s video works. With nine in total, it now holds the largest collection of what the artist called her filmworks in a public institution.

This exhibition, curated by Michael Wellen and Valentine Umansky, has been in the planning since 2022 and covers an expansive variety of the mediums Mendieta used. But rather than look at the artist’s fabled life and relationship—or, indeed, the Tate’s association with Andre—it will centre on the work itself.

“Much space has been given, in past exhibitions, catalogues and diverse other outlets, to Mendieta’s biography, somewhat to the detriment of a thorough study of her works,” Umansky says.

Mendieta’s work was highly conceptual and often ephemeral, coalescing around ideas to do with the feminine body and the relationship between humans and nature. Photographs from her Silueta series, for example, depict the ghostly impression of the artist’s body left in various outdoor environments. Works like these, Umansky says, hint “at the dual nature of the practice: outside museum walls, or as documentation of an event, already passed”.

Though the exhibition will show some of Mendieta’s early paintings in London for the first time, much of the artist’s output resists traditional display methods and the curators say the exhibition will be organised accordingly. “[Mendieta] referred to herself as sitting in the tradition of a Neolithic artist, a comment that greatly inspired us in the making of this exhibition,” Umansky says. An intricate series of drawings on leaves, for example, “present certain technical challenges given their fragility”, Wellen says.

At the other end of the size spectrum will be a restaging of an indoor forest installation that was first displayed at the State University of New York. P.J.

Dan Graham’s Bisected Triangle, Interior Curve (2002) Photo: Brendon Campos

20 Years of Inhotim

Instituto Inhotim, Minas Gerais, Brazil, from 30 August

The Instituto Inhotim, a 435-acre sculpture park and botanical garden in Minas Gerais, Brazil, celebrates its 20th anniversary this year with a year-long series of exhibitions reflecting on the museum’s history and milestones.

One of the main exhibitions, 20 Years of Inhotim, opens in August and brings together a series of archival materials and a maquette of Inhotim to help audiences grasp the size, complexity and diversity of the architecture and biomes across the property.

Outside the galleries, the exhibition includes signage highlighting significant moments, such as the installation of Tunga’s Bartunga (1989) in the late 1990s, which marked the start of Inhotim’s outdoor art collection, and the inauguration of Adriana Varejão’s pavilion in 2008, an emblematic work that combines art and landscape architecture.

The most significant part of the collection is already on display—the exhibition will be the park itself

“We struggled with the idea of an anniversary exhibition that would include artworks because the most significant part of our collection is already on display,” says Júlia Rebouças, the artistic director of Inhotim. “The exhibition will be the park itself,” she adds.

Looking ahead, Inhotim is looking to ensure its sustainability by repurposing some of the existing buildings on the estate and focusing more on long-term exhibitions rather than new artist-dedicated pavilions, as was the case under founder Bernardo Paz, the art collector and mining magnate who stepped down as Inhotim’s chairman in 2017. Since transitioning to a non-profit, the museum is primarily publicly funded and no longer receives support from Paz, whose last major project was the Yayoi Kusama pavilion, installed in 2023.

“We understand that it’s amazing to have new pavilions and galleries dedicated to artists, but, in this new moment, maybe it’s not feasible—economically, environmentally or culturally,” Rebouças says. “This year will be a very important one, not only because we’re proposing an exciting and diverse programme but also because we are marking a new chapter for the institution.” G.A.

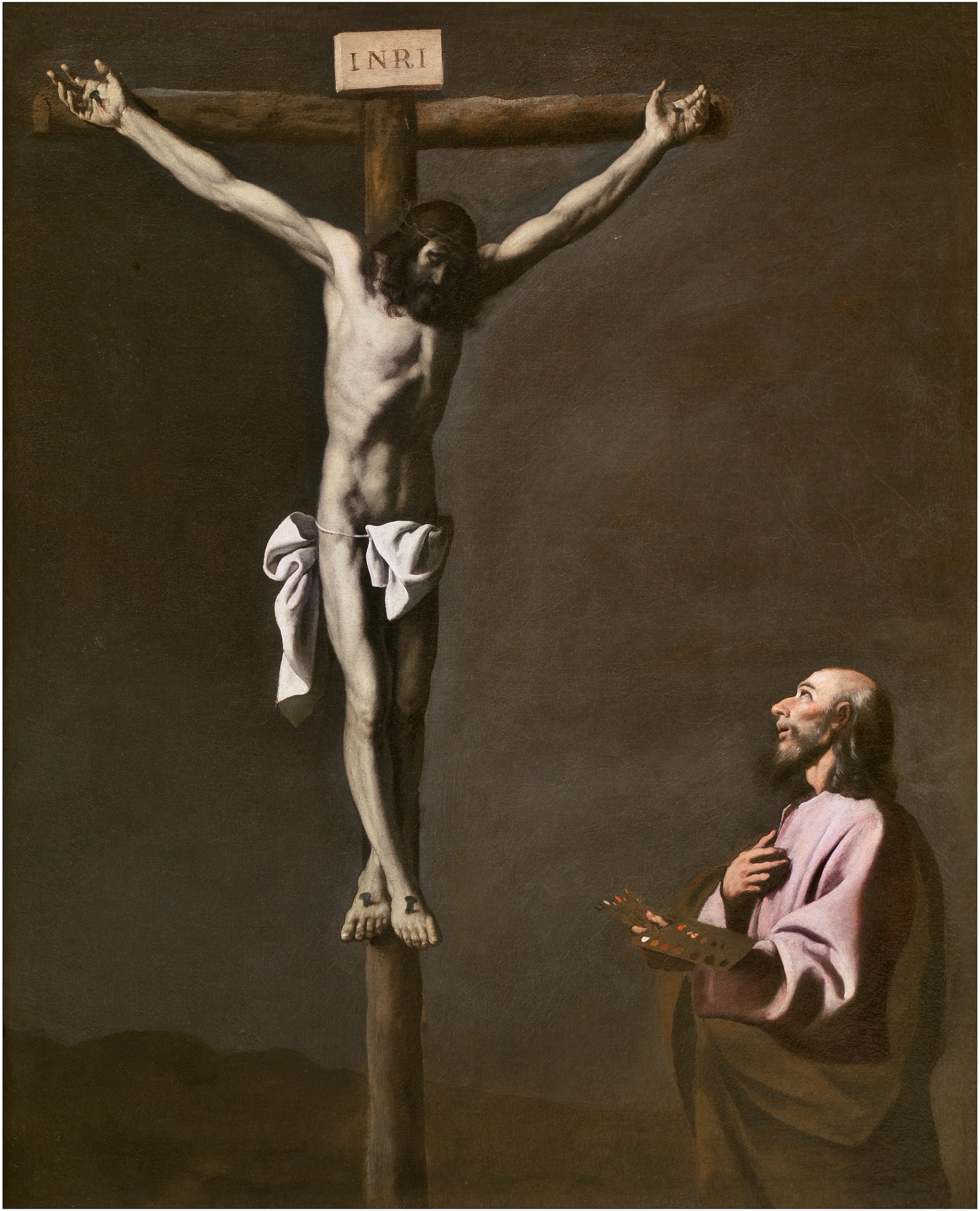

Portrait of John Baldessari Courtesy UCCA

John Baldessari

UCCA Beijing, 19 September-3 January 2027

Chinese audiences will receive an introduction to the icon of American conceptualism John Baldessari (1931-2020) at Beijing’s UCCA Center for Contemporary Art this September.

“This is Baldessari’s first exhibition in China, a project we have been developing over several years,” says UCCA curator Luan Shixuan, who organised the exhibition. Luan’s previous projects include the 2023 exhibition of eight China-born artists, Painting Unsettled, and solo shows of Elizabeth Peyton, Li Ran and Heman Chong.

“Baldessari’s legacy as both artist and educator has shaped contemporary art globally, and his conceptual strategies have long circulated—sometimes critically, sometimes productively—within China’s own artistic discourse,” Luan says. “We see this exhibition as a chance to situate his work within a broader, evolving conversation rather than to reinforce a single canon.”

Baldessari’s legacy as both artist and educator has shaped contemporary art globally, and his conceptual strategies have long circulated within China’s own artistic discourse

The show will explore how Baldessari moved from his original training in painting into exploring the possibilities within the relationships between images, texts and meanings, a practice integral to the development of contemporary art. It traces his decisive break with the past in Cremation Project (1970), burning most of his early paintings, and moving into a multi-format conceptual approach spanning photography, video, performance, film stills, collaboration and education. Baldessari’s time as an educator at Los Angeles’s California Institute of the Arts (CalArts) informed both his own work and several subsequent generations of artists through his “Post Studio Art” course.

For Baldessari’s China debut, UCCA surveys his five decades of practice, starting from his early experiments in video and text and image in the 1970s, and his 1980s montages, through to his later projects on the psychology of perception, and on colour and space and their absence. The artist’s archives, models and books fill out the show to convey Baldessari’s signature wit and his passion for questioning the established system of how art is valued and given meaning. L.M.

Sidney Nolan’s Pretty Polly mine (1948) © The Trustees of the Sidney Nolan Trust/DACS/Copyright Agency; images © Art Gallery of New South Wales

Sidney Nolan: Origins

Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 3 October-7 February 2027

Born in Melbourne of working-class Irish stock in 1917 and forced to evade the authorities after committing a crime, the artist Sidney Nolan identified with Australia’s most mythic figure—the bushranger Ned Kelly. Kelly was hanged for murder in Melbourne in 1880, while Nolan deserted the Australian army during the Second World War, but was never punished. The two crimes cannot compare, but the charismatic bushranger became a life-long theme for Nolan even after the artist left Australia in 1953 to live permanently in the UK, where he died in 1992 after a successful career and even a knighthood.

Sidney Nolan: Origins, an exhibition at the Art Gallery of New South Wales in Sydney, will focus on the artist’s Australian years and the themes that sustained him throughout the rest of his life, according to Denise Mimmocchi, the museum’s senior curator of Australian art. “I really wanted to focus on those formative years and how Nolan was responding to the different places that he visited and that inspired his experimentation,” she says.

Along with Ned Kelly—whom Nolan would paint wearing a distinctive black square helmet with an eye slot—the true story of Eliza Fraser also figures largely in the artist’s work. Fraser was shipwrecked off the Queensland coast on the island that bore her name until it was renamed K’gari in 2023. An escaped convict helped Fraser, but she turned him in when they reached safety.

Mimmocchi says the story resonated with Nolan’s sense of betrayal by his patron Sunday Reed. Nolan lived in a ménage à trois with Sunday and her husband John Reed. Sunday’s refusal to leave John was one of the triggers for Nolan to quit Australia.

The epic tragedy of Robert O’Hara Burke and William Wills was another continuing theme for Nolan. Burke and Wills died of starvation and exhaustion on an expedition to cross the Outback. “The strongest of Nolan’s works are, largely speaking, those series that he painted in Australia,” Mimmocchi says.

A highlight of the exhibition will be the National Gallery of Australia’s loan of Nolan’s Ned Kelly Series, which tells the outlaw’s story across 26 paintings and to which will be added the Art Gallery of New South Wales’s affiliated painting, First-class Marksman (1946). E.F.

Wassily Kandinsky’s Dominant Curve (1936) was exhibited at Peggy Guggenheim’s short-lived London gallery, Guggenheim Jeune, and will be on show in the touring exhibition exploring this period of the American collector’s life Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Solomon R. Guggenheim Founding Collection

Peggy Guggenheim in London: The Making of a Collector

Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice, 25 April-19 October

Royal Academy of Arts, London, 21 November-14 March 2027

The Guggenheim Jeune gallery in London was open for just 18 months. But in that time, one of Peggy Guggenheim’s least well-known ventures made waves with an array of notable firsts, including solo London debuts for Wasily Kandinsky, Yves Tanguy and the Danish surrealist Rita Kernn-Larsen.

The pioneering gallery opened its doors for the first time in January 1938, at 30 Cork Street, just a short distance from the Royal Academy of Arts, which this autumn stages a long-awaited reassessment of its impact. Organised in collaboration with the Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice, where the exhibition will debut in April, the London iteration will include around 80 works. Many of these, such as Kandinsky’s Dominant Curve (1936), for example, were exhibited at Guggenheim Jeune, but have rarely been seen in London since.

The gallery championed a roster of international abstract and Surrealist artists, among them Sophie Taeuber-Arp and Grace Pailthorpe. “Peggy Guggenheim put together a pretty incredible exhibition programme in a very short, intense space of time,” says Simon Grant, the exhibition’s co-curator with Gražina Subelytė of the Peggy Guggenheim Collection.

Noted for championing women artists, Peggy Guggenheim was similarly broad-minded in rejecting traditional genres and media

Noted for championing women artists, Guggenheim was similarly broad-minded when it came to rejecting traditional genres and media. The Russian-born artist Marie Vassilieff’s dolls would have been dismissed by many as “women’s craft”, Subelytė says. “But they were fully accepted as art, by Guggenheim.”

Controversy visited the gallery more than once: its walls were splattered with blood when the artist Cedric Morris started a fight with a visitor who objected to his portraits; on another occasion, the UK Parliament became involved when sculptures by Constantin Brâncuși and Alexander Calder, among others, were held up at British Customs, which refused to recognise them as art.

Still, little documentary evidence survives. Telling the story of Guggenheim Jeune’s prodigious exhibition programme, and understanding the look of the gallery, has taken much research.

By the summer of 1939, Guggenheim’s sights had shifted to opening a museum, which was originally planned for London before the outbreak of war changed everything. Though brief, Subelytė explains, Guggenheim’s London chapter formed the basis of all that she did next. “It was a moment where she really became very seriously engaged with [her mission as a collector] and truly saw it as her responsibility to help the artists of her own time,” she says. The exhibition will travel to the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York in spring 2027. F.H.

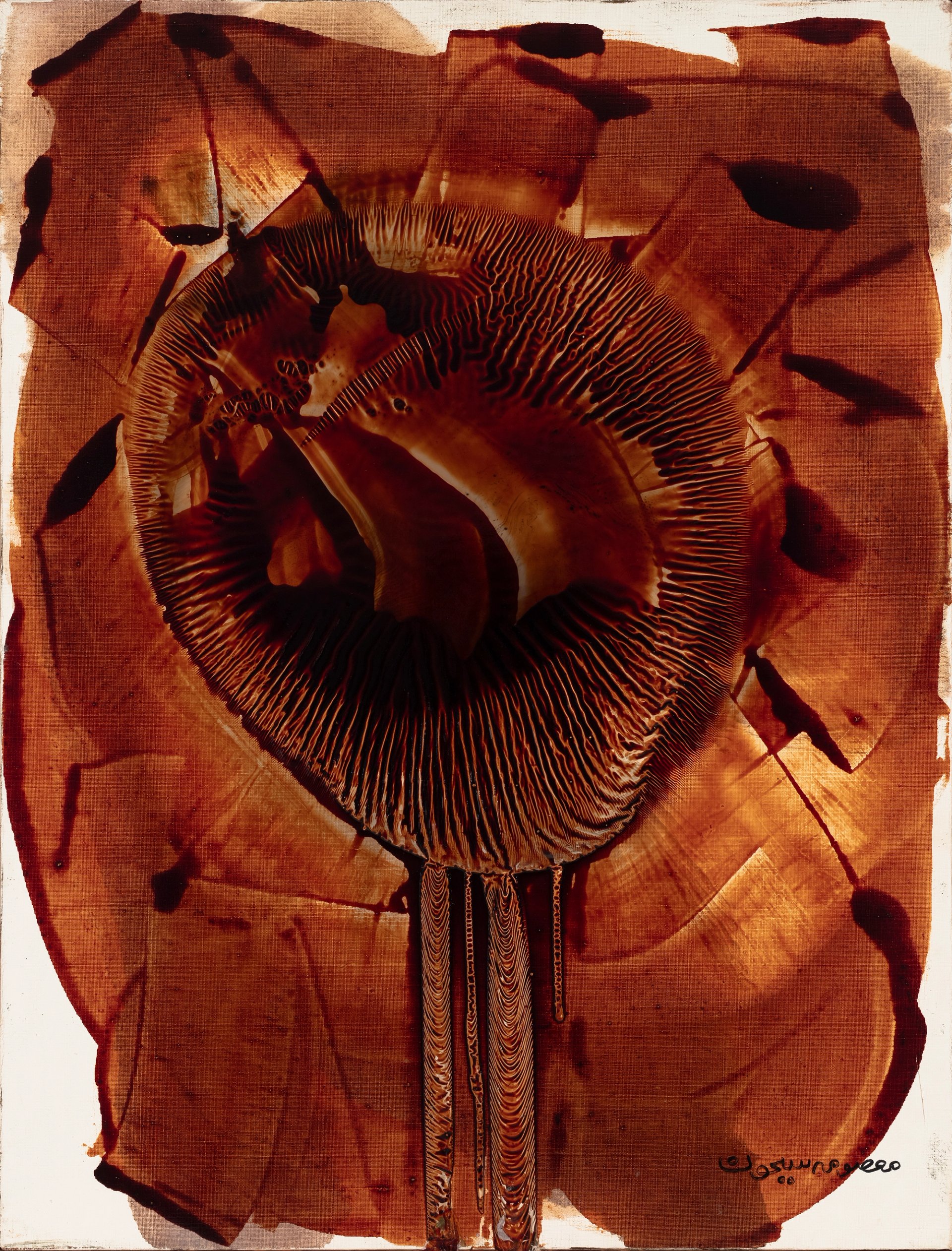

Massoumeh Seyhoun’s Composition #13 (1967) Courtesy Grey Art Museum, New York University

Modern Iran and the Avant-Gardes, 1948-78

Vancouver Art Gallery, 11 December-2 May 2027

To close the year, the Vancouver Art Gallery will explore the creative output of pre-revolution Iran, when social and political upheaval transformed a nation on the brink of a new era. In what is being billed as Canada’s largest ever exhibition of Modern Iranian art, the show will bring together around 100 works by more than 30 artists whose innovation marked a new form of artistry.

The 1979 Iranian Revolution followed a period of long-building tensions across political, social, economic and cultural sectors that converged into a mass movement against the authoritarian Pahlavi regime. Under Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the nation experienced rapid modernisation efforts that resulted in significant inequalities, alienating groups like merchants and frustrating students and workers. Many Iranians saw the monarchy as excessively dependent on Western—especially American—support and influence. Years of mass protests, strikes and ultimately a loss of military support followed, toppling the monarchy and establishing the Islamic Republic in 1979.

During the period preceding the revolution, artists responded to the widespread change, in particular conflicting notions of nationalism and religion, creating works that blended traditional Iranian iconography and Western influences, including popular styles like Abstract Expressionism and Cubism. The exhibition will trace these developments, encompassing photography, painting, sculpture and architecture. Many artists included in the show left Iran during this period and continued to work in exile.

Among the celebrated names in the show are the likes of the sculptor and architect Siah Armajani, who was a student and activist in Tehran in the 1950s, witnessing the rapid reform to education and social systems. His early work included protest collages that showed his awareness of the Western use of art to disseminate political messages. Other familiar names include Reza Mafi, who pioneered calligraphic painting and was associated with neo-traditionalism, a movement in which Iranian artists sought to create a national identity by blending aspects of past traditions with Modern styles.

Joining these are many artists showing for the first time in Canada, as well as under-represented women, including Nahid Hagigat and Massoumeh Seyhoun. Together, these artists will offer an intimate glimpse into the competing ideologies and aesthetics that set the stage for the Iranian Revolution. A.K.