It is dangerous to use art fairs as a barometer of making and meaning in contemporary art. But walking through Frieze London’s carpeted aisles in October, a long-developed hunch was confirmed emphatically: we are amid a deluge of bad painting.

It is not good “bad painting”, in the late Francis Picabia sense. It is bad bad painting. Bloated, vapid, performative (not in the good sense) painting. Stultifyingly boring painting. Market-slump painting. “Oh-why-not?” painting.

The exhibition Painting After Painting: a Contemporary Survey from Belgium at the SMAK museum in Ghent between April and November was less disquieting. (Full disclosure: I led a panel at SMAK on the subject of painting with two curators of recent surveys, Lydia Yee and Manuela Ammer.) But while the intellectual framework around the show was robust and thoughtful and the presentation absorbing, with plenty of examples of engaging work, a lot of it still felt thin in subject or wanting in execution.

This is perhaps inevitable in any survey of 74 artists working in a particular medium in a single country. But as a devout, passionate defender of the discipline’s unique properties and powers, I can’t remember being so often at a loss to find merit in paintings as I have been in the past couple of years.

I wonder: has painting become too comfortable? No one says painting is dead anymore. It never will be, of course. But with no ideological objections it isn’t forced to defend itself, to come out fighting. Some of the best painting of the past century was made in times of crisis and reckoning, when artists using paint felt embattled or disenfranchised from the central discourse.

A brush with… Christopher Wool—podcast

I was reminded of this when I interviewed Christopher Wool on the A brush with… podcast in October. We spoke about his reflection that the moment where the Renaissance gave way to the Baroque was comparable to the shift between Modernism and postmodernism that was happening when he emerged as an artist in the late 1970s. Both situations—moments of crisis or upheaval—liberated artists. Wool suggested that “we’re experiencing a real lack of that now, or that’s my impression, anyway. Those kinds of dialogues are rare now.” I asked if he meant a critical dialogue where ideas are on the line. He responded that artists in the late 1970s “really had to deal with some of these issues… you couldn’t really ignore them”. I asked if artists were literally discussing whether painting was dead in their studios. “There were plenty of people not far from me who really believed painting was problematic and should be avoided in some way,” he replied.

‘Obscurity and ambiguity’

Wool then mentioned a marvellous piece of critical writing from that time: Thomas Lawson’s 'Last Exit: Painting', published in Artforum in October 1981, in which Lawson, himself a painter, argued that painting can be the “unsuspecting vehicle” that camouflages radical ideas. Crucial to painting’s potency in opposition to the photographic practices trumpeted by those marking painting’s demise, Lawson suggested, was its capacity for obscurity and ambiguity. He saw the work of the Pictures Generation artists, such as Richard Prince and Cindy Sherman, as “straightforwardly declarative”. It therefore leaves no room for a factor that I believe remains one of contemporary painting’s superpowers, and an animating force for much of the best painting since that period: harnessing what Lawson calls “the growth of a really troubling doubt”.

Doubt was a productive force for an artist of terrific importance for Wool in his early years—Philip Guston. Guston’s own response to a painting crisis, choosing figuration over abstraction, literally prompted friends to turn their backs on him. I regard Wool’s recent paintings in oil as reanimating some of Guston’s questions.

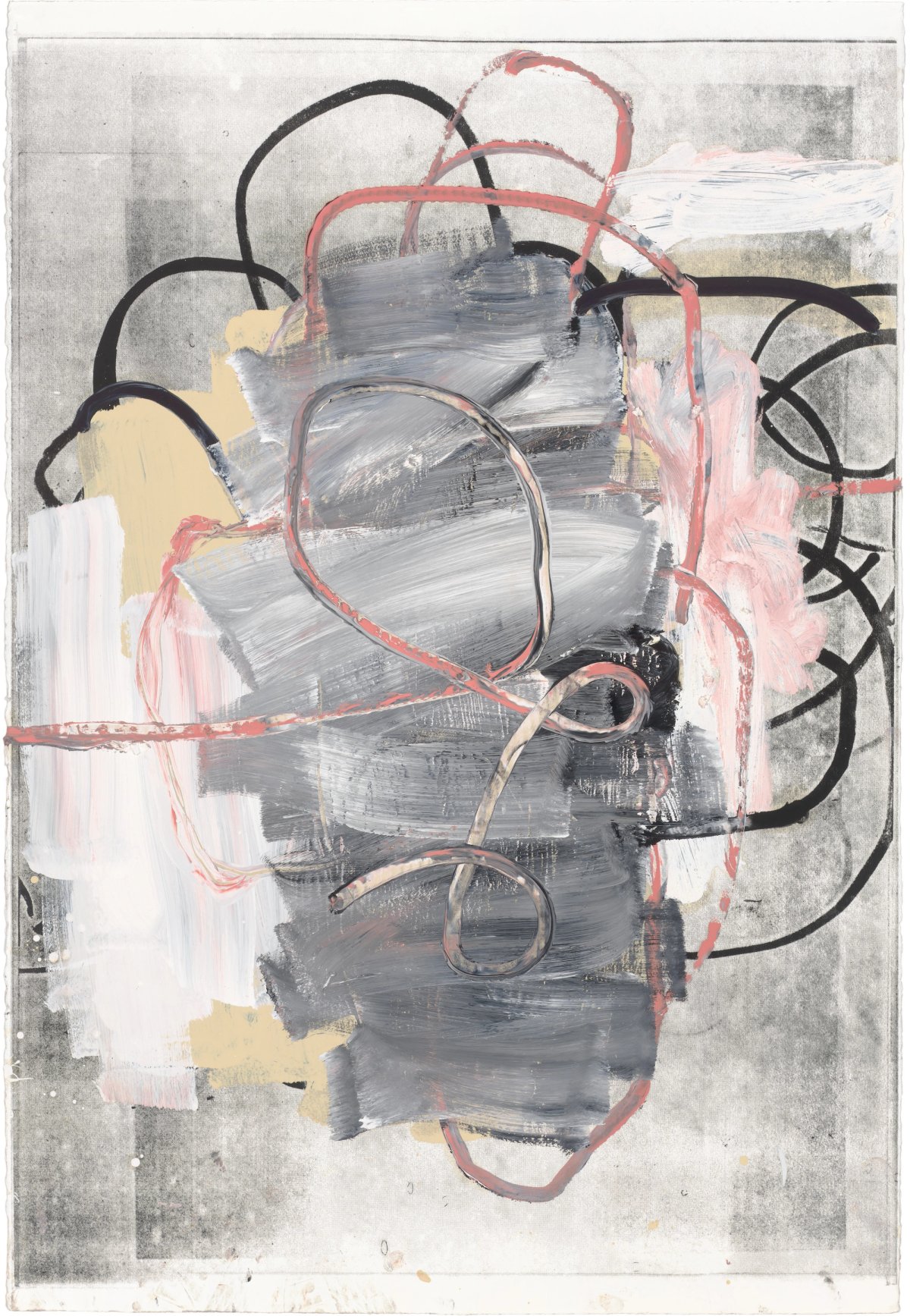

It seems no accident that the four painters whose shows I have most admired in recent months—Wool at Gagosian, Kerry James Marshall at the Royal Academy of Arts and Peter Doig at the Serpentine, all in London, and Charline von Heyl at Xavier Hufkens in Brussels—forged their painterly languages at moments of fierce debate about the possibilities, and pitfalls, of the discipline. An anything-goes climate is not healthy for painting. Just because we are past the painting-is-dead moment does not mean the fight for its relevance is over.