“I don’t want to be Botero or only a lady who paints,” Beatriz González said in the early 1960s, a statement she would later revisit. It captures the path forged by the Colombian artist, writer, curator, educator and intellectual—known as la maestra—who died in Bogotá on January 9 at age 93.

Born in 1932 in Bucaramanga, the capital of the department of Santander, González often recounted an early anecdote. When she was ten years old, when a nun at her school showed Beatriz’s drawing of a tangerine to her classmates and declared: “This is an artist.” That early affirmation stayed with González, who briefly studied architecture at the Universidad Nacional de Colombia before enrolling at the Universidad de los Andes, where she studied fine arts.

González came of age in a turbulent context in Colombia, when other forms of expression, such as abstraction or the distinctive style of her contemporary Fernando Botero, reigned. “For her, originality and uniqueness were important,” says Natalia Gutiérrez, who, since 2016, has been González’s assistant and adviser. Gutiérrez has curated exhibitions, including, with Pollyana Quintella, the ongoing retrospective of González’s work at São Paulo’s Pinacoteca (until 1 February), which will travel to London’s Barbican Centre, marking her first UK retrospective, and end at Oslo’s Astrup Fearnley Museet.

Beatriz González, Telón de la móvil y cambiante naturaleza (Backdrop of a Moving and Shifting Nature), 1978 Collection of the artist. Photo: Andrés Pardo

“From the outset, she pursued a different kind of figuration, breaking conventions about what was expected of women artists,” Gutiérrez says. Influential figures like the art critic Marta Traba took González under their wing.

González was also a key figure in Colombia’s museum sector. She was among those involved in the opening of the Museo de Arte Moderno de Bogotá (Mambo) in 1963. She held her first solo exhibition there in 1964, presenting her series La Encajera (The Lacemaker), inspired by Johannes Vermeer’s painting. The series reflects her reinterpretation of Western artworks’ reproductions, which she adapted into furniture, wallpapers and curtains.

“Unlike Pop art inspired by mass culture, González took canonical artworks as referents, infusing them with locally sourced kitsch,” says Cuauhtémoc Medina, who co-curated the exhibition Guerra y Paz: una poética del gesto (2023-24) at the Museo Universitario de Arte Contemporáneo (Muac) in Mexico City with Gutiérrez. “Her ironic self-description as a provincial painter also marked a different route from mainstream art by approaching a subaltern aesthetic.”

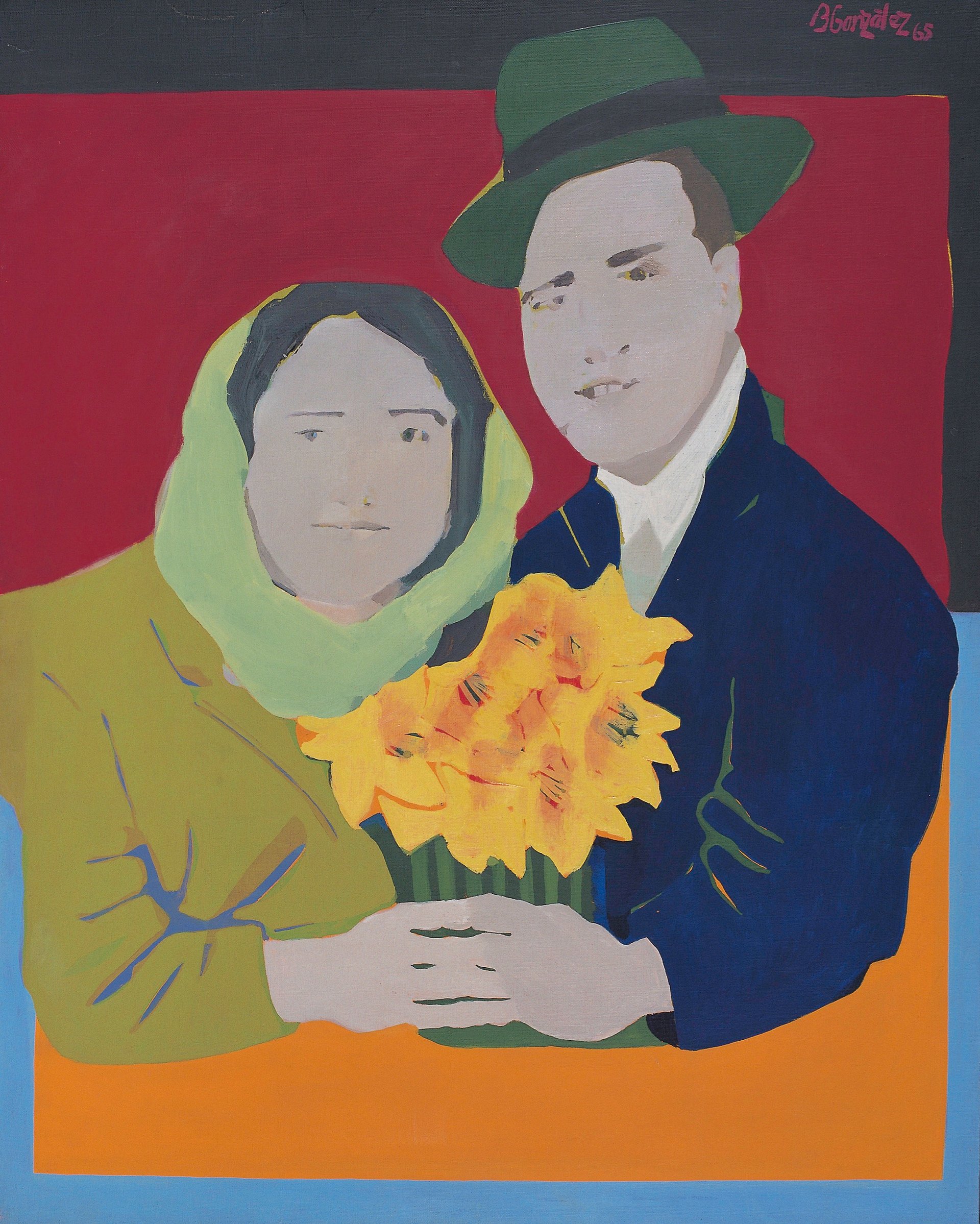

Beatriz González, Los suicidas del Sisga III (The Sisga Suicides III), 1965 Museo Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá. Photo: Óscar Monsalve

One of González’s best-known works is the series Suicidas del Sisga (1965), based on a photograph of a young couple who later died tragically. The work marked a turning point in her practice, as she began using photographs from the local press, depicting them with flat forms and a vibrant palette. “The series marked a route of expression for Beatriz through appropriation, which made some link her to Pop art, an association she rejected,” Gutiérrez says. “Using this route, she changed her approach over time, synthesising the local context.”

Throughout her career, González played a crucial role in art education and museum practice in Colombia. In 1978, she envisioned a school for museum guides at Mambo that would transform art pedagogy nationwide. She later reinterpreted the collection of the Museo Nacional de Colombia and served as its chief curator between 1989 and 2004. She was also a pioneering researcher on Colombian caricature and 19th-century Colombian art, and a mentor. “Many of Colombia’s present-day museum professionals were shaped by González in one way or another,” Medina says.

Beatriz González at work in her studio Courtesy Casas Riegner, Bogotá

All the while, she archived documents related to her practice, art history and journalism. In 2020, she donated her extensive archive to Banco de la República, specifying that it should be kept in her hometown. Medina describes her as a “public intellectual figure”, noting how her work captured the country’s complex context and, more importantly, portrayed human experiences and gestures, particularly grief.

This is evident in González’s public art project Auras anónimas (Anonymous Auras, 2007-09) at Bogotá’s Cementerio Central, dedicated to the country’s disappeared. Conceived at a time when the columbarios—spaces holding the remains of anonymous victims—risked demolition, the work comprises thousands of headstones painted with black silhouettes of figures carrying the deceased. “I want to captivate the auras of the thousands of dead who may be floating here and to offer a space where those who wish can mourn,” González once said of the project.

“Beatriz was instrumental in reshaping readings of Colombian contemporary art, foregrounding how local conditions articulate broader issues of memory, authority, political imagery and collective mourning,” says Paula Bossa, the director of Casas Riegner in Bogotá, which has represented González since 2012.

Beatriz González, Dolores (Pain), 2000 Photo: Juan Camilo Segura

“González was a critical force within Latin American art,” says Tobias Ostrander, co-curator of Beatriz González: A Retrospective(2019), the artist’s first large-scale US retrospective at the Pérez Art Museum Miami. “Her trajectory moved from using humour in engaging media images, toward paintings criticising political figures involved in perpetuating violence in Colombia, to empathetic images paying homage to endurance amid suffering.”

González remained active until recently, traveling to her shows while maintaining a busy schedule back home. “Beatriz did not differentiate her artistic practice from her other interests,” Gutiérrez says. “Her life was a generous, multifaceted commitment to culture.”