For over a century, Graubünden has had a special place in the visual arts, fostering and fashioning a number of key figures of European Modernism. Marked by high mountains and remote valleys, Graubünden is not only enormous by Swiss standards, it is also exotic. In a country divided up by language, it is the only trilingual canton, with Romansh, an alpine descendent of Latin, joining Italian, spoken in a few valleys, and German, which dominates in and around the regional capital, Chur. This is the place to start an art-minded tour of the canton. Chur’s Bündner Kunstmuseum has important holdings related to its native daughter Angelica Kauffman, one of the 18th century’s leading women artists, and the Giacometti family, who have their roots in the Bergell Valley. But manifold and surprising works of art, architecture and design are spread throughout, from the Vals valley in the west to the Müstair valley in the east, which is walking distance to Italy and biking distance to Austria.

Ferdinand Hodler, Lake Geneva with the Savoy Mountains (around 1907)

Bündner Kunstmuseum Chur

Switzerland’s master Symbolist Ferdinand Hodler (1853-1918) was born in Bern and influenced by the Old Masters he encountered in Basel, then settled in Geneva. By the early 20th century, his national standing—achieved through patriotic, stylised paintings and frescoes—meant that he had the means to devote himself to landscapes, which became his favoured genre. This small work (pictured above), with intimations of abstraction, compresses Geneva’s nearby mountains into a barely jagged shelf, reflecting the artist’s proclivity for horizontal compositions, even when depicting soaring Alpine peaks.

Alberto Giacometti’s Landscape Near Stampa (1952), on view at the Bündner Kunstmuseum Chur © 2025 Succession Alberto Giacometti/DACS; Courtesy of Bündner Kunstmuseum Chur

Alberto Giacometti, Landscape Near Stampa (1952)

Bündner Kunstmuseum Chur

Alberto Giacometti (1901-66) altered the course of 20th-century art from his Paris studio, but his roots were in Graubünden’s Italian-speaking Bergell Valley, where his artist-father, Giovanni, had roots. Philippe Büttner, a senior curator at the Kunsthaus Zürich and managing director of Switzerland’s Alberto Giacometti-Foundation, says the artist had “a very strong connection to his native country”, and frequently returned to the Bergell Valley for weeks at a time. He died in a Chur hospital and was buried in his native Bergell village near Stampa. Back in Paris, his recurring subjects were his wife, Annette; his younger brother Diego, who shared his studio; and his studio itself. But when his mind returned to Graubünden, he often depicted landscapes.

Frescoes from the Abbey of St John in Müstair Stiftung Pro Kloster St Johann, Müstair

Frescoes from the Abbey of St John (around AD800/1000s-1100s)

Müstair

Though a birthplace of Modernism, Graubünden has monuments dating back to the Middle Ages. Likely founded by Charlemagne around 780, the Abbey of St John, in the Müstair valley, was named one of the earliest Unesco World Heritage sites back in 1983 due to its frescoes. The best known date to the ninth century; others, from the 11th and 12th centuries, were only rediscovered in the 20th century. Superbly preserved in the mountain air, the frescoes show scenes from the life of King David; the life and passion of Christ; and the crucifixion of St Andrew.

Angelica Kauffman’s Self portrait with Bust of Minerva (1780-81) Bündner Kunstmuseum Chur

Angelica Kauffman, Self portrait with Bust of Minerva (1780-81)

Bündner Kunstmuseum Chur

Angelica Kauffman (1741-1807) was nothing if not cosmopolitan. Though born in Chur—where her father, an Austrian painter, was in service to the town’s bishop—she trained in Italy and made her career in Britain, where she was a founding member of the Royal Academy of Arts. Noted in her lifetime for Neoclassical history paintings, she was also a gifted portraitist, and her grand clientele included everyone from Naples’s royal Bourbons to Joshua Reynolds. But she was also a keen self-portraitist, taking herself as her own subject around two dozen times. This iteration in Chur, in which she is shown holding a pencil and folder of drawings, is among the best.

James Turrell’s Skyspace Piz Uter (2005) Photo: Kamahele; © James Turrell

James Turrell, Skyspace Piz Uter (2005)

Hotel Castell, Zuoz

Zuoz, the historic heart of Graubünden’s Upper Engadine region, sits at around 1800 metres above sea level. Like other areas in this corner of Switzerland, it became a health resort around 1900. The village’s Hotel Castell, built in 1912, expanded its portfolio in the 1990s to include contemporary art. In addition to a bar designed by the Swiss artist Pipilotti Rist, it also has a permanent installation by the US artist James Turrell (born 1943), whose subject, medium and obsession is light. The rotunda-shaped work—also known as the Turrell Tower—allows for an ever-changing view of the sky, brought in through an opening in the ceiling and affected by shifting colours of artificial light.

Robert Maillart’s Salginatobel Bridge (1929-31) Taljat

Robert Maillart, Salginatobel Bridge (1929-31)

Schiers

Robert Maillart (1872-1940), the Swiss architect-poet of reinforced concrete, designed this acclaimed bridge to cross an alpine ravine in the Prättigau, near the ski resort of Klosters. A marvel of engineering, running around 135m long while hovering 90m above a stream, it gleams like steel, with a floating appearance that almost suggests plaster. Used as a teaching aid for architects and engineers around the world, and a tourist attraction in its own right, it is also a work of Minimalist art, avant la lettre.

Peter Zumthor’s Therme Vals (1996) Felipe Camus

Peter Zumthor, Therme Vals (1996)

Vals

When the Swiss architect Peter Zumthor (born 1943) won the Pritzker Prize, architecture’s highest honour, in 2009, he had produced a mere smattering of buildings, and this hotel bathing complex was probably the most admired. Built out of locally sourced quartzite slabs, it is a fully functional, discreetly luxurious spa. But it is also frankly sculptural—a usable work of art. On the inside, the layout alternates light with shade, along with open and closed spaces. On the outside, the structure itself suggests a fusion of the man-made with the natural—you never quite know if you are looking at a perfectly formed rock formation or an eerily natural building.

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner’s Davos with Church in Summer (1925) © Stephan Bösch, all rights reserved

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Davos with Church in Summer (1925)

Kirchner Museum Davos

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (1880-1938) became the most urbane of Germany’s Expressionists in the years just before the First World War. Following a nervous breakdown during the war, he moved to Davos, known for its sanitoria. He spent much of the next two decades here, where he eventually killed himself in 1938, distraught by developments over the border in Nazi Germany. His artistic legacy, housed in his namesake museum, is the resort’s leading cultural attraction. This work, which views the village from the north, pits the church against the towering Tinzenhorn mountain.

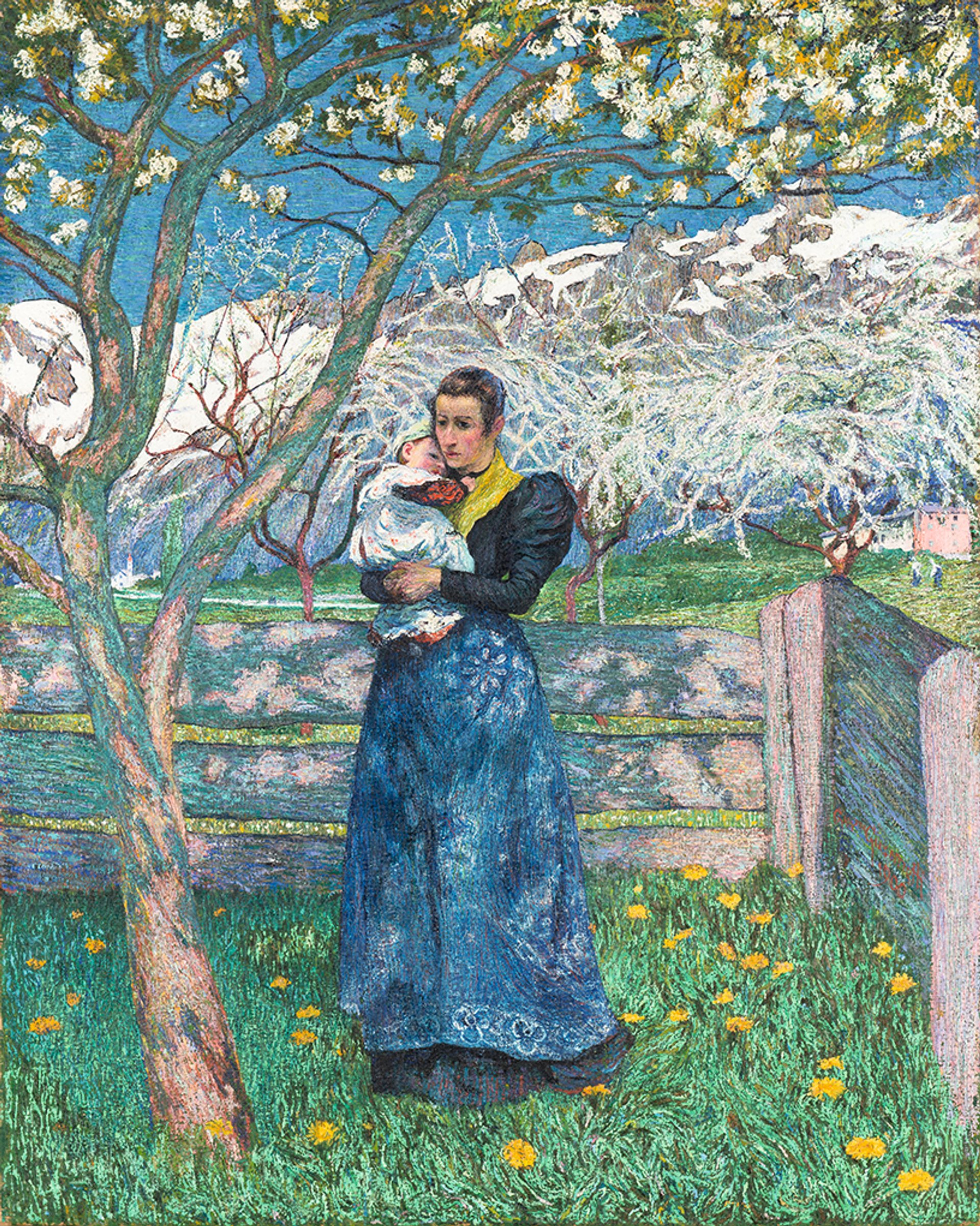

Giovanni Giacometti’s Fioritura (1900) Bündner Kunstmuseum Chur

Giovanni Giacometti, Fioritura (1900)

Bündner Kunstmuseum Chur

The son of a Bergell village baker, Giovanni Giacometti (1868-1933) launched his artistic dynasty after leaving Graubünden for studies and sojourns in Munich, Paris and Rome. He finally returned to Switzerland, broke and broken down, in the early 1890s. Befriended and encouraged by the painter Giovanni Segantini, he made his name as Switzerland’s leading post-Impressionist, imparting rustic and alpine settings with a kind of Fauvist fury. Although his son Alberto would all but abandon colour, Giovanni never let go of his fabulous palette, on display in this springtime scene, where the blue-patterned skirt plays off flowering trees and distant snow cover.

Giovanni Segantini’s Nature (1897-99) Segantini Museum

Giovanni Segantini, Nature (1897-99)

Segantini Museum St Moritz

Born near Italy’s Lake Garda when it was still part of Austria, Giovanni Segantini (1858-99) found refuge in the upper reaches of Graubünden’s Engadine Valley when he was not yet 30. The region’s transformative light and peasant struggles became his recurring subjects, rendered in a pioneering Modernist manner that has placed him alongside Edvard Munch, James Ensor and Vincent van Gogh. His namesake St Moritz museum, which opened a matter of years after his death, is a kind of walk-in monument. Its permanent collection includes this signature work, in which the dominant Engadine sky is represented by broken brushwork.