Until last year I thought my father, Samuel Kahn (1927-2007), had largely wasted his life. But as I tremblingly type this essay, I am headed to a Virginia museum displaying a roomful of his psychedelically colourful, unselfconscious, off-kilter, long-forgotten works of art that, it turns out, make people happy.

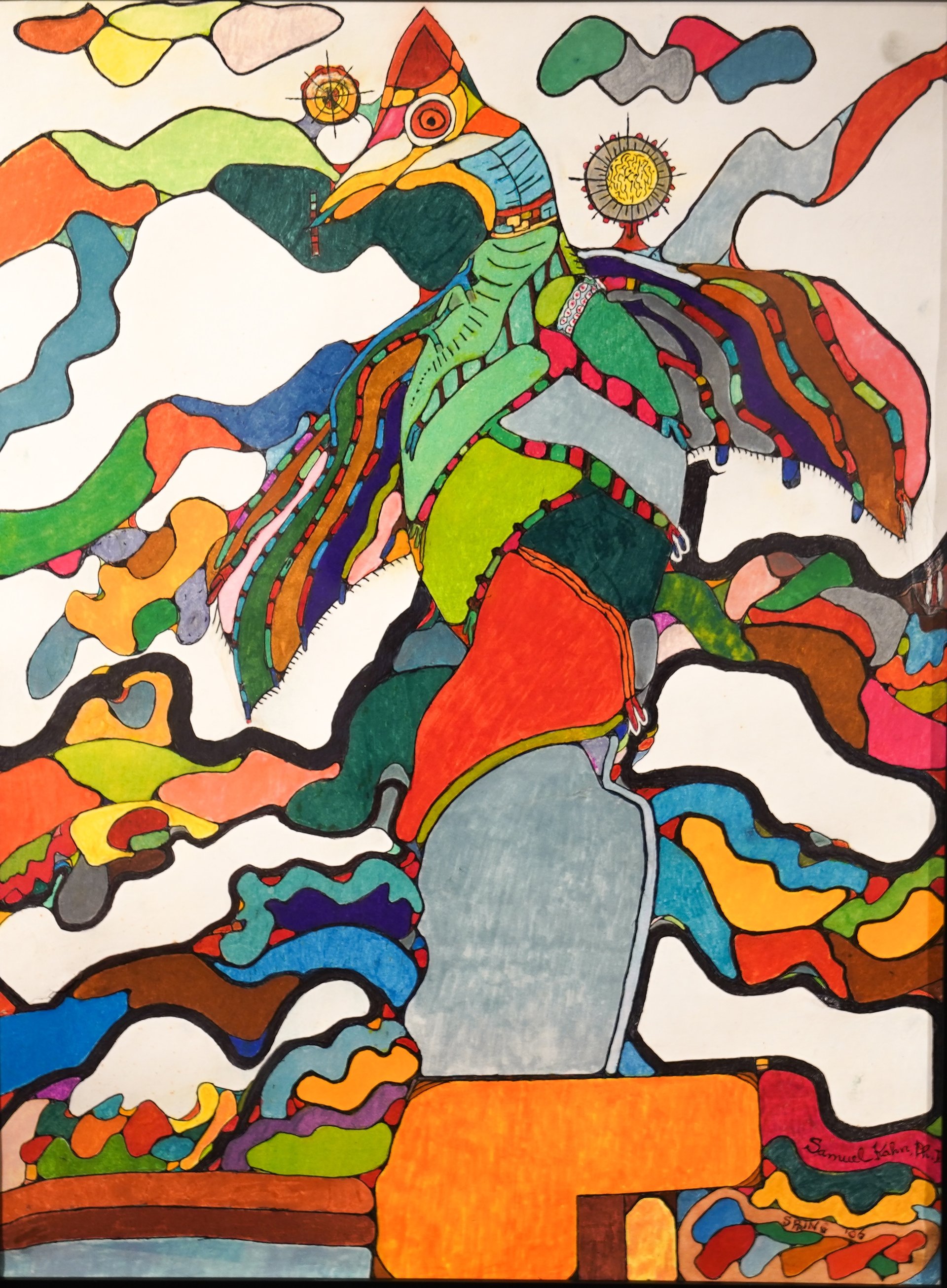

The exhibition Samuel Kahn, Ph.D. + Friends opens on 29 January at Old Dominion University in Norfolk, Virginia, in its Gordon Art Galleries. It features around 50 of Dad’s wood-carvings, paintings and sketches. In intense hues—he had no art training and never learned to mix paint—amoebas drip over kaleidoscopic cats gamboling on housetops. Mermaids sprout weathervanes. Fish spin on pedestals. Trees resemble brain lobes.

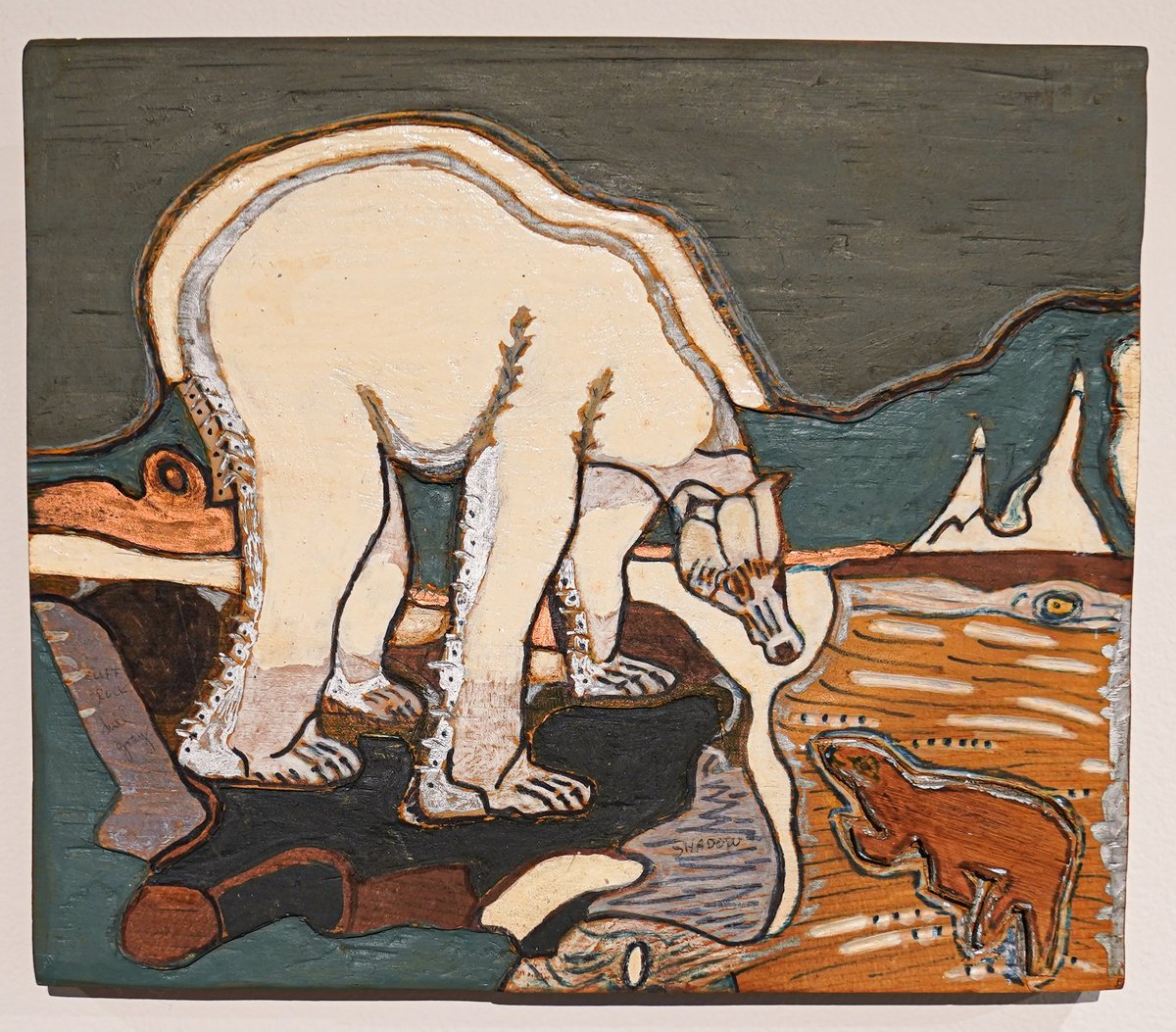

Dad’s titles are just as enigmatic: Two Friends in Tow + Cloudburst (around 2003), Trials & Tributaries on the Rocky Road to Birdland (1997). He carefully labelled some elements—grey triangles are “Canyon-Like Hills”, a snaking white streak flecked in black is “Sandy Debris Frozen River”—as he tried to impose order on a world made incomprehensible by his failing mental health.

Samuel Kahn’s Two Friends in Tow + Cloudburst (around 2003) Courtesy Old Dominion University Gordon Art Galleries, Norfolk, Virginia

Jasper Waugh-Quasebarth, the show’s curator and the Gordon Art Galleries’ director, describes Dad’s work as radiant, prismatic and “grounded in earthy, natural materials”. Waugh-Quasebarth and other scholars have even compared Sam Kahn to Peter Max, Grandma Moses, Marc Chagall and the Cubists. Dad knew a little about those luminaries, since my mother Renée Kahn was an art teacher, historian and artist in her own right. But Dad emphasised his art-world outsider status by adding “Ph.D.” to his works’ signatures—referring to his Columbia University doctorate in clinical psychology specialising in children, which did him little professional good.

He was a Montreal native, whose Lithuanian Jewish immigrant family ran clothing stores. In 1957, while finishing his studies at Columbia, he married Renée—a Bronx-born, City College-educated daughter of Ukrainian Jewish immigrants. In the 1960s, with three children in tow (me and my older brothers, Andrew and Ned), my parents settled into an old farmhouse in Stamford, Connecticut, where my dad worked at children’s clinics. He was tall, athletic and hearty-looking but beset by bipolar depression. Rounds of electroshock treatments left him frail, befogged and eventually unemployable. I believed, by age four, that demons possessed my father.

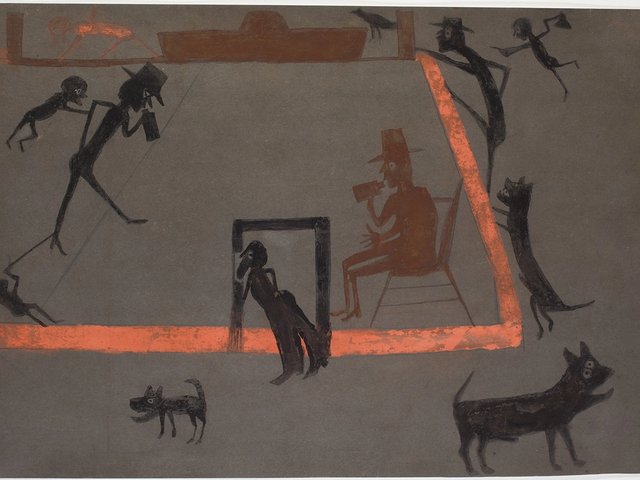

As our savings ran out, Dad found solace in tending the farmhouse and its grounds, with oaks and maples shading magnolias, roses, peonies and phlox. My mother eked out a living by teaching and consulting in the art and architecture world. She painted prolifically in her free time, inspired by the German Expressionists—especially George Grosz. In her signature works, neon signs glow amid tableaux of caricatured gangsters, corrupt politicians, strippers and gossipy housewives.

Samuel Kahn’s Untitled (2006) Courtesy Old Dominion University Gordon Art Galleries, Norfolk, Virginia

My mother's pursuits laid some groundwork for my own career. Since the 1980s, I have written about art and architecture for publications including The New York Times. My brother Ned, meanwhile, became a sculptor—the exhibition at the Gordon Art Galleries includes his and Renée’s works as well.

Around 1990, Dad started experimenting with my mother's paints. On large wooden panels, he floated images of wildlife over Stamford streetscapes and—why not?—dangled apples from a basketball hoop. He kept scrapbooks of clipart that inspired him, including John James Audubon’s bird prints. As his increasingly violent mood swings alienated everyone except Renée, my Dad compulsively sketched whirling amoebas—he felt it was his calling, and a way to connect with loved ones.

After he died, his accumulated works only worsened our grief. My art-world contacts suggested donating them to a museum. Old Dominion accepted the cumbersome gift as a favour to their galleries’ endowers, Baron and Ellin Gordon (my husband’s cousins). We tucked away a few carvings—a winged horse, a spinning fish—but largely forgot about Dad’s obsession.

Samuel Kahn’s Pegasus Flying Home (around 1995) Courtesy Old Dominion University Gordon Art Galleries, Norfolk, Virginia

In late 2024, when my mother sold the farmhouse and moved into assisted living, I received an email from Waugh-Quasebarth out of the blue. The art of Samuel Kahn, Ph.D., with its “flowing lines and bright colours”, had been rediscovered in storage, and he was planning a show including related pieces by renowned artists like Dale Chihuly.

I wondered at first how I could bear having Dad’s work spotlighted, given all my childhood scars. I would never have predicted that, by 2026, I could write this reflection and tell people: “Here’s some good news in these mostly terrible times: I’m not mad at my dad anymore. His art is bringing joy.”

To inform Waugh-Quasebarth's exhibition labels, I cathartically pored over family papers. I found material I had forgotten or never seen: an early 1960s photo of confident Dad analysing a child’s drawing of a gabled house, his Audubon scrapbook, his 1990s self-published book about appreciating trees titled Barks That Don’t Bite. When Waugh-Quasebarth came to our Manhattan apartment to pick up our exhibition loans, I took notes for this article as he reminisced about feeling “just captivated and curious” at the first sight of Dad’s art.

A dozen supportive friends and relatives are joining me for the opening at the Gordon Art Galleries, as throngs of strangers puzzle over Two Friends in Tow and Cloudburst. Back at our apartment, I have already begun to miss the winged horse and spinning fish.

- Samuel Kahn, Ph.D. + Friends, Gordon Art Galleries, Old Dominion University, Norfolk, Virginia, 30 January-16 May