The lawyer and social-justice activist Bryan Stevenson first founded the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) in 1989, when he was 29 years old. His goal was to provide legal representation to death-row inmates and others unfairly treated by the criminal-justice system. But in the decades that followed, EJI has pursued efforts outside the courts, in the form of memorials and museums, to end narratives of racial inequity and to memorialise historical harms.

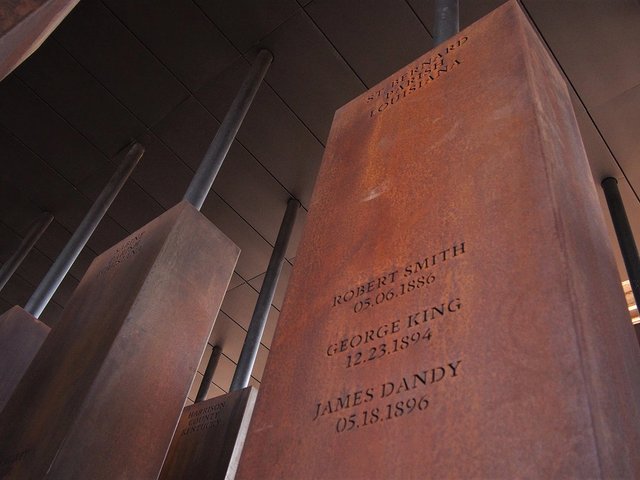

EJI’s first Legacy Sites, the Legacy Museum and the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, opened in 2018 in Alabama’s state capital of Montgomery. Through first-person historical narratives, documents, artefacts and art, the sites serve as memorials to victims of racial violence and chronicle the unresolved trauma of slavery, segregation and lynching. The Legacy Sites project expanded in 2024 with the 17-acre Freedom Monument Sculpture Park, which honours the 10 million Black people who were enslaved in the US with site-specific works created by contemporary artists.

Over the years, hundreds of thousands have visited Montgomery’s Legacy Sites, and the project’s reach continues to expand. A new hotel and convention centre spearheaded by Stevenson opened last year to complement the sites. Meanwhile at the sculpture park, a site-specific work by the conceptual artist Charles Gaines was unveiled. And this month the newest Legacy Site, Montgomery Square, is scheduled to open—an exhibition hall and garden exploring Civil Rights activism in the 1950s and 60s.

“I think this is an incredibly important moment, and I’m feeling really grateful to be surrounded by people and working with artists and others who are helping us try to meet this moment with a deeper commitment to truth telling, not a retreat from truth telling,” Stevenson tells The Art Newspaper. He adds that the US cannot move towards a just future without addressing its painful past.

Stevenson’s great-grandparents were enslaved, and he attended segregated schools as a child before the supreme court ordered them integrated in 1954. Stevenson witnessed first-hand how the rule of law could intervene where political process could not. Later in life, his work as a trial lawyer enabled him to see connections between enslaved people in cells and those incarcerated behind bars, and how narratives outside the courtroom reinforced these connections.

“We are in a narrative struggle,” he says. “There’s a narrative rooted in fear and anger that is raging, and when people allow themselves to be governed by fear and anger, they start tolerating things you should never tolerate, accepting things you should never accept. It’s what leads to some of the worst moments in human history.”

To counter these kinds of harmful narratives, Stevenson started with small but impactful markers of the history of enslavement and began developing the Legacy Sites, powerful “truth-telling spaces” in the form of museums, monuments and parks that both lay bare the US’s history of slavery, lynching and racial violence and honour its victims.

Archival image of one of the marches from Selma to Montgomery for voting rights, March 1965 Courtesy of the Equal Justice Initiative

Southern trees bear a strange fruit

In 2025, Freedom Monument Sculpture Park debuted Gaines’s new work Hanging Tree. The park, sited along the Alabama River and hemmed in by railroads built using forced labour, honours the lives of the enslaved—away from the sweeping but deceptive grandeur of a plantation. It includes an authentic slave dwelling; sculptures by Alison Saar, Kwame Akoto-Bamfo, Simone Leigh, Wangechi Mutu, Rose B. Simpson, Theaster Gates, Kehinde Wiley and Hank Willis Thomas; and the 155ft-long National Monument to Freedom.

Gaines’s steel-and-bronze work depicts an uprooted tree secured by a noose swinging from a post. The octogenarian artist took cues from Billie Holiday’s sombre 1939 song Strange Fruit, and he conceived of the tree as a metaphor for the legacy of lynchings.

“Strange Fruit, the song, refers to a body swinging, a strange fruit swinging. And the idea of fruit and bodies gave me the idea to employ motion to the object,” Gaines told EJI in October. “And I think that that deepens the emotional reality of lynching—not literally, but very poetically. And it is that emotion that’s important in order to keep this idea of the immense immorality, the awful nature of finding a way of legitimately hanging people.”

Gaines said his time at the Legacy Sites was one of triumph; it provided answers to questions that have haunted him his whole life. Born in 1944 in Charleston, South Carolina, he is old enough to have experienced Jim Crow laws and a segregated South.

The newest Legacy Site picks up on this part of the storyline—the pivotal years leading up to the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965. Montgomery Square explores the large-scale activism and legal reforms of the decade that dismantled codified racial segregation. It uplifts the voices and actions of both famous and lesser-known figures in the fight for Civil Rights—including the 1955-56 Montgomery bus boycott, which followed the arrest of Rosa Parks for refusing to give her seat to a white person, and the 54-mile protest marches in 1965 to Montgomery from Selma, Alabama.

Martin Luther King Jr and John Lewis were among the leaders of these events, as were activists like Claudette Colvin, Sheyann Webb, and Lynda Blackmon Lowery. Through images, archival research, art and interactive audiovisual components, Montgomery Square visitors learn about individual acts of courage and the collective power of resistance in the face of systemic, racist and violent opposition.

Mugshots of participants in the 1955-56 Montgomery bus boycott on display at the Legacy Museum in Montgomery, Alabama Courtesy of the Equal Justice Initiative

Creating a different America

Stevenson is careful to note that Montgomery Square is not a museum of achievement and closure. “I’m excited about reinterpreting this aspect of the Civil Rights Movement and focusing more on courage and commitment and the work that remains, rather than pure achievement and success,” he says. “It’s a constant struggle, and I think that’s the idea we want to animate in this space.”

Stevenson cites the Voting Rights Act, which prohibits voter discrimination based on race, as one of the most significant pieces of legislation—both when it was first enacted and today. “It has radically changed the economic, social, political and cultural landscape of this country, because when millions of Black people finally were able to vote, everything shifted. Everything changed,” he says. “And now we’re seeing a retreat from that, which is part of the reason why understanding this history and its significance is as timely, important and urgent today as it was 60 years ago when those people marched.”

The defining visual of Montgomery Square is a series of mugshots that intentionally invert images usually tainted with negativity. The 115 organisers and activists who took part in the Montgomery bus boycott faced their arrests (for an act of nonviolent resistance) with pride. Their official police photos, part of the archival display at the new Legacy Site, also served as inspiration for a new site-specific work by Hank Willis Thomas. Other commissioned art there includes pieces by Basil Watson and Ronald McDowell. Poignantly, Stevenson saved a tree on the site slated for removal—an old oak that was witness to the city’s historic events.

“What people were doing in Montgomery between 1955 and 1965—they weren’t just trying to get the right to sit on a bus,” Stevenson says. “They were trying to create a different America.”