Forty years after The Last Resort photobook was first published, the photographs that brought the late Martin Parr to international attention—and criticism at home—will be the focus of an exhibition at his foundation in Bristol.

Timed to coincide with the anniversary of the photobook and its exhibition at London’s Serpentine Gallery in 1986, the show marks the foundation’s reopening following the British photographer’s death late last year. Presented as a tribute to what Parr repeatedly described as his most enduring work, it will display the full original sequence, as well as some of the images not used in the book, and draw on archival material to give new context to the project.

Parr had enjoyed modest success with earlier black-and-white series, but after returning from the West of Ireland with his wife, Susie, he began developing a new visual language that embraced colour and was less nostalgic about British quirks. Parr’s photographs of New Brighton, a beach resort near Liverpool, had been shown alongside Tom Wood’s works at the city’s Open Eye Gallery the year before, to little controversy. But after the exhibition at the Serpentine, Parr suddenly had access to a much wider audience, gaining new fans abroad while drawing some acerbic criticism at home, accusing him of cruel voyeurism.

Contact sheet from The Last Resort © Martin Parr/Magnum Photos

The photographs were different from anything British viewers had seen before—and not just because they were shot in colour with the clarity of medium format, which was more closely associated with commercial imagery at the time. What really irritated some British critics was that Parr appeared to be a middle-class interloper, slumming it in the north of England during the divisive years of Thatcherism, and his pictures did not romanticise.

“Our historic working class, normally dealt with generously by documentary photographers, becomes a sitting duck for a more sophisticated audience,” wrote David Lee in Arts Review. “They appear fat, simple, styleless, tediously conformist and unable to assert any individual identity.” Meanwhile, in the British Journal of Photography, Robert Morris described the images as showing a “clammy, claustrophobic nightmare world where people lie knee-deep in chip papers, swim in polluted black pools and stare at a bleak horizon of urban dereliction”.

This idea that Parr was punching down, laughing at his subjects, took hold, and it resurfaced again when he died. Writing in the 2002 Phaidon catalogue of Parr’s work, which accompanied a major touring exhibition starting at the Barbican in London, the show’s curator Val Williams provided some nuance. “It wasn’t frightening or disgusting, or even controversial,” she wrote. “It was comical, touching, skilfully seen, lively, vigorous… It was unfortunate this [critical] response, sparse and uninformed as it was, somehow came to be seen as a debate. The Last Resort contains some unforgettable photographs. It’s lyrical as a great pop song, as raucous as a music hall.”

An image from Parr’s The Last Resort © Martin Parr/Magnum Photos

What the 40-year distance now makes clear is that the “controversy” never really belonged to the photographs. It belonged to a British critical culture acutely uncomfortable with working-class visibility, and to a moment in the mid-1980s when politics, class and moral panic were tightly entangled. Parr’s photographs did not provoke debate so much as reveal how poorly equipped critics were to look without prejudice.

It is rarely mentioned that Parr and his wife were living in nearby Wallasey at the time. “If you think about the early days of Martin’s work, he was photographing the areas where he was living and working,” says Dewi Lewis, who knew Parr since the mid-1980s and published many of his books, including the first reprint of The Last Resort in 1998. “I was brought up in Rhyl in north Wales, which is very similar to New Brighton. I worked in the amusement arcades,” Lewis says. “I did all the summer jobs that you do in that sort of place. So I knew those people. And I knew that there was no sense of it being exploitative.”

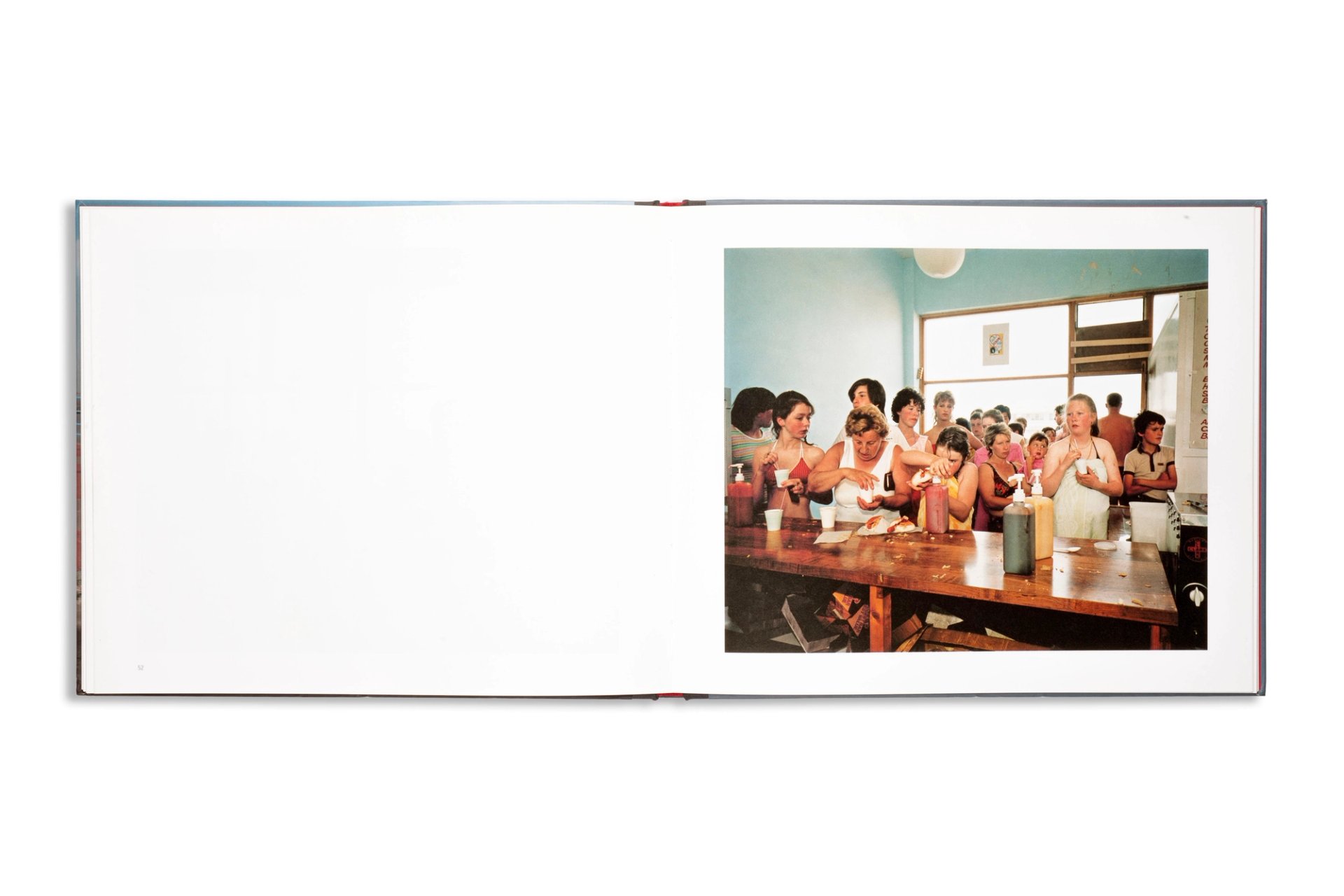

A spread from the 2008 edition of The Last Resort; a facsimile of the photobook is due out later this year © Martin Parr

The exhibition at the Martin Parr Foundation will present criticism and correspondence around the work’s making and reception. The staff—some of whom worked closely with Parr for a decade—have also been documenting the recollections of the individuals involved in the making of the project, including Peter Brawne, who did the original book design. This design will be replicated for a 40th-anniversary facsimile edition that will be published by Dewi Lewis in the autumn.

Another contributor is the photographer’s wife, Susie Parr, now a trustee at the foundation, who recalls life in Wallasey, where they bought a house overlooking the River Mersey. “I would roller skate down the prom to catch the ferry and the no. 84 bus to work,” she writes. “Martin would cycle the other way to New Brighton. Having recently left the gorgeous beaches and clean seas of the West of Ireland, I personally found New Brighton a bit much, what with all the pollution and litter. It was incredibly run down, truly a sign of the times in Thatcher’s Britain. Having been very fond of Martin’s more elegiac black-and-white work in Hebden Bridge and Ireland, the brash colour of his images was a shock. But I could see that it was an extraordinary body of work.”

• The Last Resort, Martin Parr Foundation, Bristol, 20 February-24 May