Amita Shenoy, curatorial consultant to Lawh Wa Qalam: M.F. Husain Museum, was the curator of Husain’s museum in Bangalore from 1995 until it closed in 2007. During those years, she came into close contact with the artist: “It helped that I knew his likes and his dislikes,” she tells The Art Newspaper. “I would always think of his point of view when I was curating.” Here, she selects six works from the collection in Doha that she feels tell the story of Husain’s life and work.

1. The Raman Effect series (1987)

In 1930, C.V. Raman (1888-1970) became the first Indian and the first non-white person to win the Nobel Prize in Physics. He was knighted the same year and became a cultural hero in independent India. Raman studied the relationship between light and colour, giving his name to the “Raman effect”, which described the way light changes as it passes through different media.

As such, it is especially fitting that, in Husain’s 1987 series, which commemorated Raman’s centenary, he brought his trademark angular forms of searing colour almost to the point of abstraction. These colours are arranged dynamically on the canvas, deployed economically but deftly to suggest rapid movement, and are intended to be a visual representation of Raman’s theories. According to Shenoy, Husain believed “that science and the arts are parallel pursuits of the same truth”.

Courtesy of Qatar Foundation

2. Arab Astronomy (2008)

After Husain moved to Qatar in 2010, he began to indulge his interest in the legacy of Arab writers and philosophers throughout history—a subject that was close to his heart because of his Muslim faith and Arab ancestry.

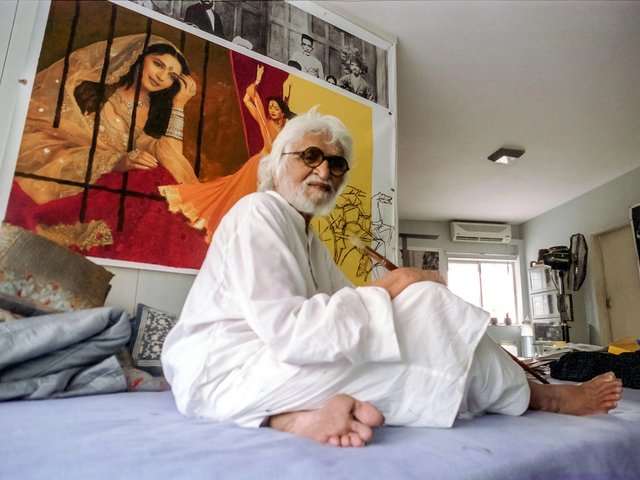

In his final large-scale commission, Husain was asked to create 99 works on different aspects of Arab civilisation; the number was chosen in a nod to the number of names and attributes used to describe Allah in classical Islamic thought. He completed 36 before his death and in one of them, Arab Astronomy, a large but tightly packed canvas, Husain depicts the astrologer Abu Ma’shar, whose shocking white beard recalls Husain himself, walking by the shores of the Persian Gulf below a stylised and almost celestial background. The viewer’s eye, which lingers on the grey boulders of the bay, will find that they are actually made of human form: we can see a reclining woman stretched across the bottom of the painting, her hand on a book in the far-right corner.

According to Shenoy, this is the artist’s nod to “the idea of history getting lost” amid an unstable multiplicity of narratives. It’s a topic that may have had personal resonance for Husain, whose work, which was ultimately rejected by the country of his birth, always engaged directly with the political issues of his day.

Courtesy of Qatar Foundation

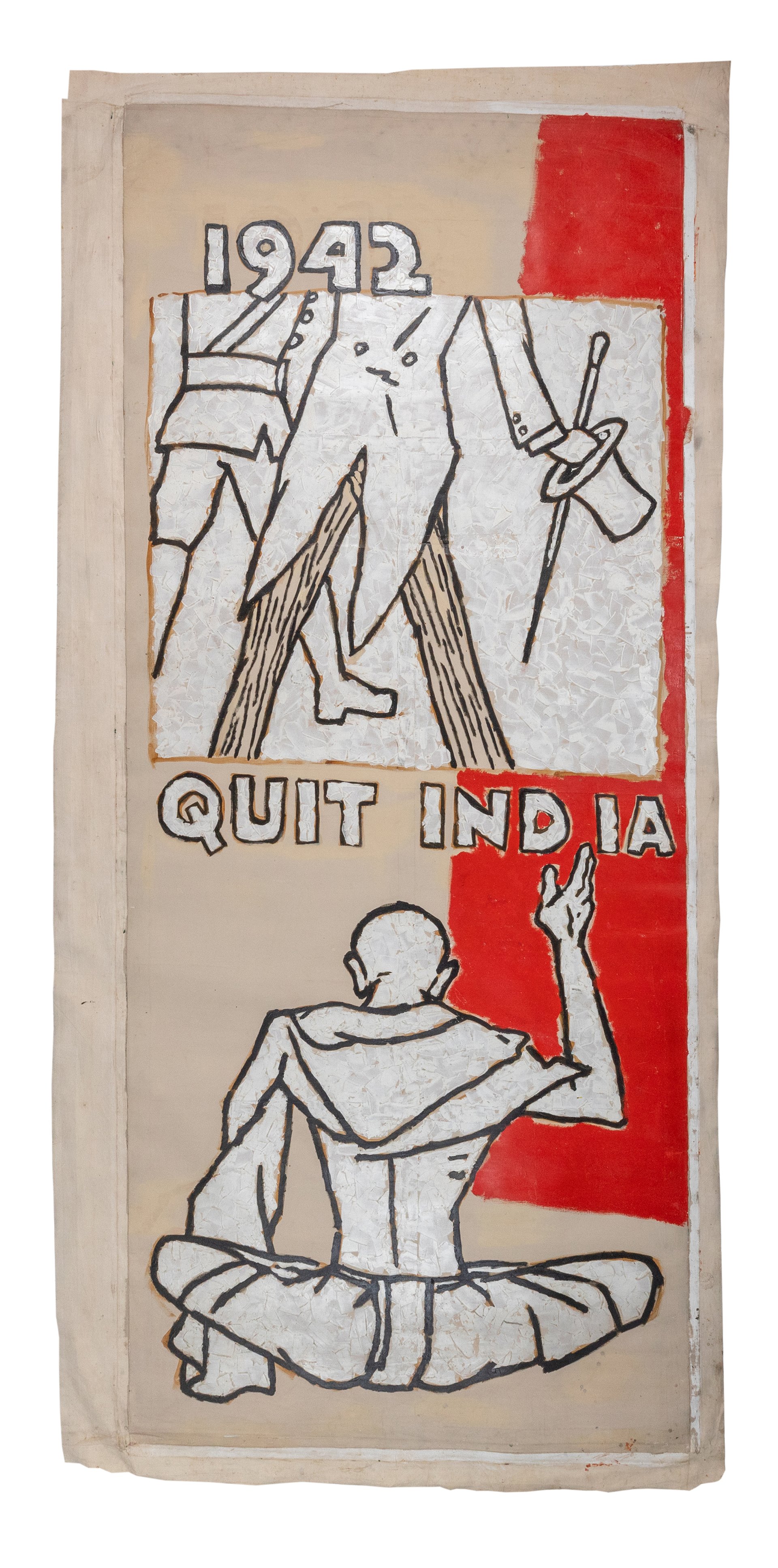

2. Quit India Movement (1985)

In 1942, around the time Husain was starting a family as a young man in Bombay, Mohandas (Mahatma) Gandhi, who had been at the forefront of Indian politics for three decades, launched his Quit India Movement. It led to a dramatic intensification of nationalist political activity in the country. The Indian National Congress had initially taken a much gentler attitude towards British rule, but things had changed. At the outbreak of the Second World War, the Viceroy of India, Lord Linlithgow, failed to consult any Indian politicians before announcing that the country would fight with the Allies. He soon had a full-scale non-co-operation movement on his hands, led by a man who could use nationalist and religious rhetoric to mobilise tens of millions of Indians to demand immediate independence.

The birth of an independent India can be traced to Gandhi’s movement. It was opposed by Hindu fundamentalists and by the Muslim League, which was led by Mohammed Ali Jinnah, later the first leader of Pakistan, and opened up divisions among Indian politicians that would later cause the subcontinent to become divided on lines of religion.

In the summer of 1947, tens of millions of Hindus and Muslims left their homes forever; it is said that up to a million people died on the way. As a Muslim, Husain might have migrated to Pakistan, as his contemporaries, such as the Pakistani painter Sadequain and the Indian artist Krishen Khanna, did.

But Husain was always a believer in the Indian national project: a secular, inclusive state that could incorporate all the myriad strands of cultural influence that were indigenous to the country. In 1963, he painted from life a monumental portrait of India’s first prime minister, and Gandhi’s close associate, Jawaharlal Nehru. He continued to enjoy the support of Nehru’s daughter, the sometimes autocratic Indian leader Indira Gandhi, until her assassination in 1984.

In Quit India Movement, Husain presents the audience with “a lived experience, not just a record of history”, says Shenoy. “It’s his sensitive response to seeing suffering around him.” Three panels of the original 100ft-long series are on display in Doha. With a steely political clarity, they depict the frail, ascetic Gandhi, clad in his loincloth (dhoti), as a heroic figure defiantly resisting India’s colonial rulers. With the benefit of hindsight, they look today like a programmatic statement of the political ideals that Husain staked his life on.

Courtesy of Qatar Foundation

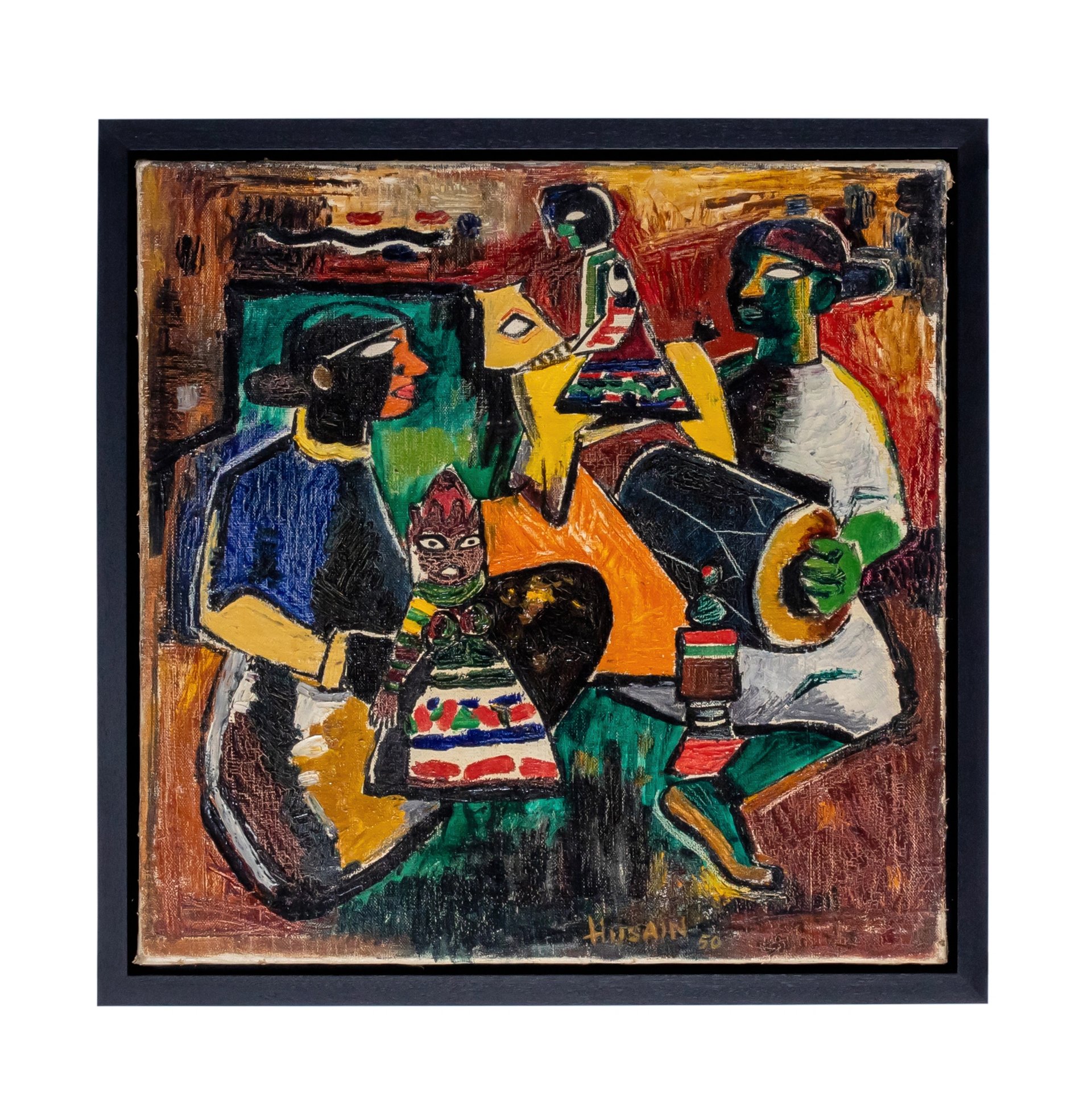

3. Doll’s Wedding (1950)

Given that the display of Husain’s paintings from the 1950s is exceedingly rare, Doll’s Wedding is therefore one of the museum’s standout works.

It was painted at one of the most pivotal moments in the art history of the subcontinent, when young artists were grappling with being the thought leaders of new, independent entities, but also the inheritors of long, tangled traditions.

It was perhaps the most original moment of Husain’s career, when he was playing around with what became his signature look: bold black lines enclosing indistinct, shimmering blocks of colour; angular figures arranged with considerable—and meaningful—tension; and the playful assertion of Indian heritage. “There is more power, more freedom” in these works, says Shenoy, who speculates that Doll’s Wedding might bear the influence of movie posters; in the early 1940s, Husain had supported his young family by painting banners and posters for Mumbai’s cinemas. In this piece, much like in a film poster, several stages of action are contained within one tableau.

According to Shenoy, it is a “celebration of Indian marriage traditions in the form of dolls” and draws heavily on “the warm, earthy colours used in traditional weddings” such as red and orange.

In a nod to Husain’s engagement with the myriad traditions of Indian folk art, Doll’s Wedding depicts a musician playing the tabla, an Indian drum.

Courtesy of Qatar Foundation

4. The Artist and his Model (1994)

Husain may have first made his name as a painter and draughtsman, but he could switch medium and genre with ease. In the 1960s he tried his hand at making films; in the 1980s he designed his first building—a villa in Delhi for the industrialist D.K. Modi; and in the 1990s he experimented with tapestry-making, a nod to India’s ancient traditions of textile art.

According to Shenoy, one such tapestry in the museum’s collection, The Artist and his Model, showcases Husain’s “perpetual exploration of other mediums; it expresses the same fluidity and freedom as his paintings in the form of tapestry”. It depicts a human figure, representing Husain himself, together with a horse, perhaps his most famous motif and one that reappeared in his work over the decades. But, for Shenoy, this tapestry is all about the nature of artistic inspiration: “All of the other horses in his paintings are shown in full flowing energy, but this one shows Husain in an intimate closeness with his inspiration.”

Courtesy of Qatar Foundation

5. Humanism (2003) from the Theorem series

In 1995, a Hindu nationalist government took control of Husain’s hometown of Bombay, changing its name to the more Sanskrit-sounding Mumbai, and he was charged with blasphemy barely a year later. An innocuous naked sketch of Saraswati, the Hindu goddess of wisdom, created more than 20 years before, was reproduced in a newspaper with the headline “M. F. Husain: A Painter or a Butcher?” The problem was not the depiction itself—Hindu gods had been depicted in the nude for centuries and continue to be across India—but, rather, that it came from a Muslim artist.

After the Gujarat riots of 2002 and India’s first Hindu nationalist federal government, ruling from 1998 to 2004, the country’s sectarian right felt emboldened to intensify their attacks on Husain. Always keen to tackle issues head on, he began to lean even more into religious themes in his work at a time when he was more famous for controversies over blasphemy than for his pioneering artistic idiom.

In 2003, he embarked on one of his most ambitious projects, Theorama, a 10-part series commissioned by the Hinduja Group’s charitable foundation celebrating the religions and philosophies associated with Indian history. In Humanism—a work which, surprisingly, contains no humans—Husain depicted the concept as a tent, representing what Shenoy calls “the common human quest for peace and spirituality”.