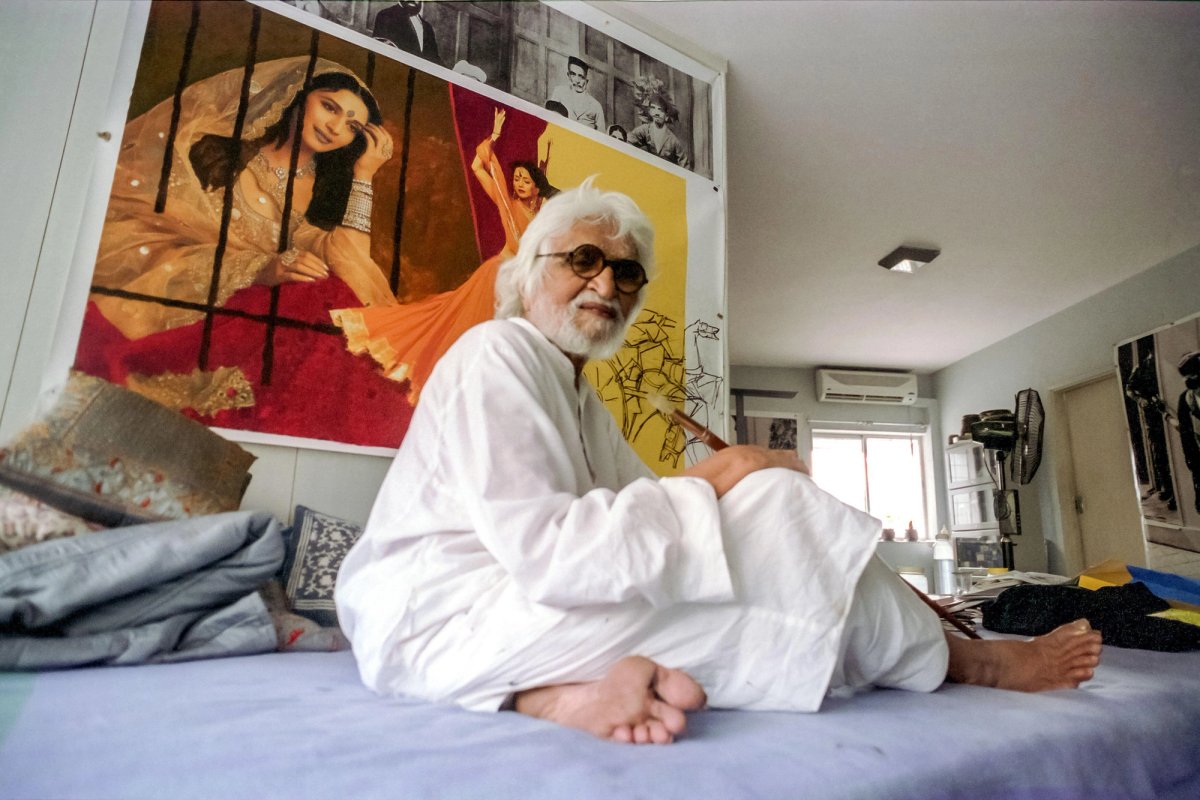

Maqbool Fida Husain is often called India’s answer to Picasso. Both men achieved pre-eminence among their peers, and, in life as in art, they were nothing if not distinctive. And both men encapsulated the political history of their time and place. If Picasso lived out the making and breaking of European society in the 20th century, the story of M.F. Husain is the story of India. He was shaped by—and shaped in turn—the forging of an independent, self-confident democratic state from the rump of the British Raj.

But, by the time he died in London in 2011, he was no longer a citizen of India, but a Qatari, having moved to the Gulf state in 2009 and accepted citizenship the following year. What does it mean then that Husain, so often claimed as the “national artist” of India, spent his last years in Qatar? Lawh Wa Qalam: M.F. Husain Museum, seeks to answer that question.

Husain’s monumental Battle of Badr (2008), which he painted at the age of 95 Khalid Abdulrahman/© Qatar Foundation

Husain was born in 1913, to a Shia Muslim family of distant Yemeni heritage in the small town of Pandharpur, around 200 miles southeast of Mumbai (then Bombay)—a glittering, cosmopolitan mercantile hub, home to India’s canniest politicians and richest businessmen. He came of age in the febrile years leading up to the country’s independence in 1947—and the violent Partition that, for a time, threatened to shatter the fluid, syncretic milieu in which Husain began to work as a young man. Together with a diverse group of artists known as the Progressives, Husain innovated a unique artistic idiom, forward-looking and yet rooted in the visual and cultural traditions of the subcontinent. “I thought we must find our own roots,” recalled Husain decades later. “I must find a bridge between the Western technique and the Eastern concept.”

He produced a body of work explicitly concerned with Indian heritage—drawing on folk art, religious iconography and cultural traditions—but which had a startlingly contemporary look, in keeping with trends in global Modernism. He also drew inspiration from the ideology and character of the nation state of which he chose to become a citizen.

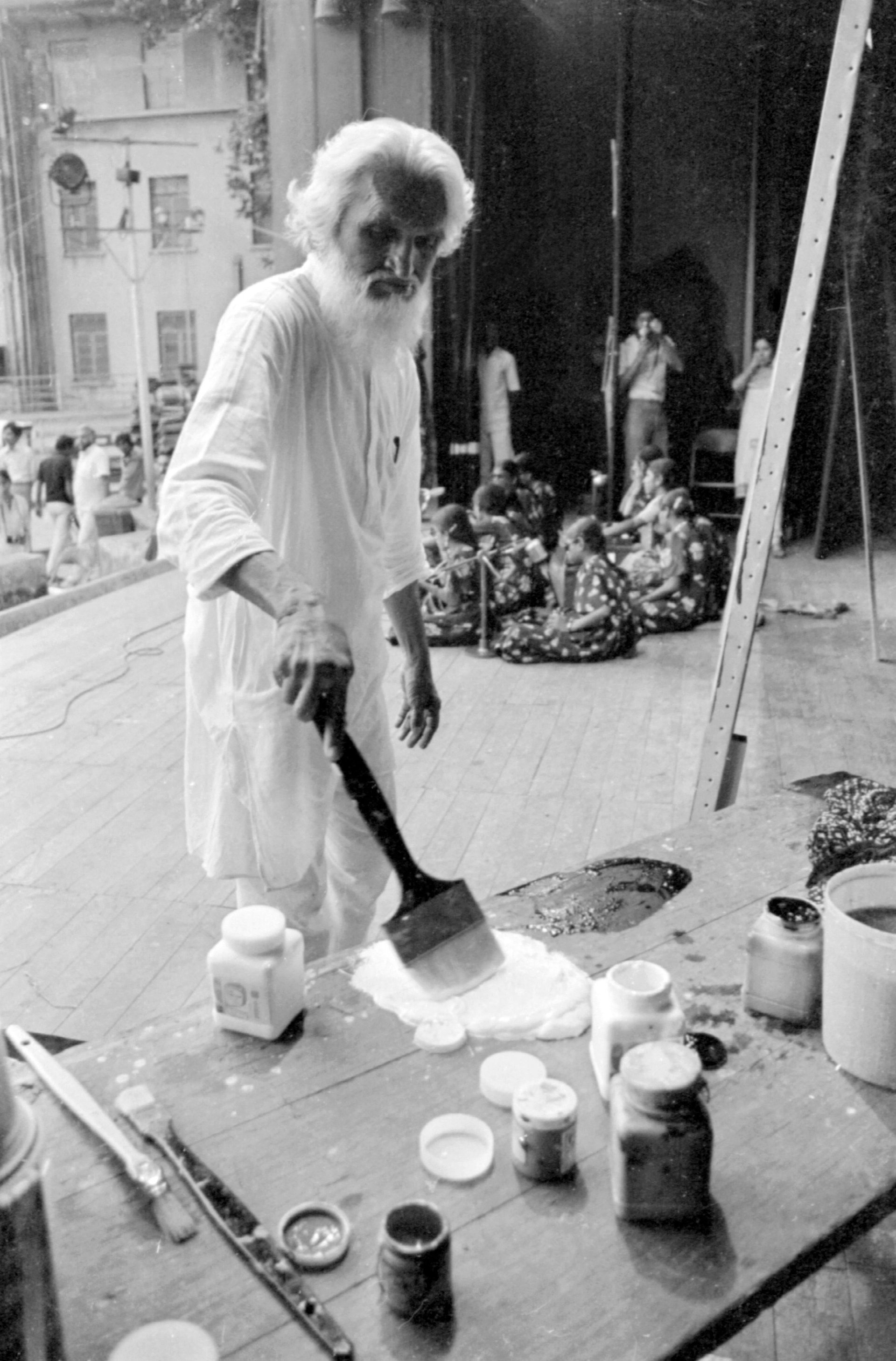

The artist in the process of creating work Dinodia Photos/Alamy Stock Photo

“Husain wasn’t just an artist,” the art historian Zehra Jumabhoy tells The Art Newspaper. “He represents a particular vision of a secular India.” Husain was a practising Muslim—and an international playboy who followed some religious rules more rigorously than others—but he placed India’s multiplicity of identities at the heart of his work, celebrating Hindu divinities and epics alongside giants of Urdu literature like “Allama” Muhammad Iqbal.

Time and again, he painted the country’s political and ideological leaders, including a striking portrait of India’s first prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru in the Doha collection, and a controversial 1975 work of Nehru’s daughter Indira Gandhi in the guise of Durga, the many-armed Hindu goddess of war; at the time, Gandhi had suspended civil liberties in a two-year period of autocratic rule known as the “Emergency”. Husain served for six years as a senator for Gandhi and Nehru’s party, the Indian National Congress, which remains associated with a secular political identity.

However, Husain’s career as a poster boy for that secular vision ran headlong into controversy after 1996, when he was accused of blasphemy for depicting a Hindu goddess in the nude. Receiving little official support—he was even charged with “hurting religious sentiments”—by the 2000s Husain found it impossible to continue to live and work in India. “He was hugely disappointed [after 1996], because it was a politically motivated campaign,” says Dadiba Pundole, who was Husain’s friend and gallerist for two decades. “But his belief in a Nehruvian secular India didn’t change at all.”

Husain’s cut-out work Elephant (1992), which reflected his

enduring fascination with Indian culture © Qatar Foundation

In this context, “he found in Qatar a supportive environment for his artistic practice”, says Noof Mohammed, the curator of Lawh Wa Qalam. It also marked a departure for the artist in theme and content: “We became fast friends,” recalled Sheikha Moza bint Nasser, the mother of the current Emir of Qatar, in a speech at the museum’s opening. “Just as Maqbool swiftly rediscovered his sense of belonging by returning to his Arab cultural roots.”

Around the time he moved to Qatar in 2009, Husain, who had always courted large-scale patronage, took on a massive project called Arab Civilisation: 99 works on different aspects of Islamic and Middle Eastern history, commissioned by the Sheikha and inspired by Husain’s new engagement with the Middle East, after he had spent most of his career focused on Indian civilisation. “He was embracing other aspects of world culture and his own identity,” Jumabhoy says. “So one shouldn’t say he was exploring the fact that he was Muslim specifically—he had a more philosophic way of looking at it in his later years.” Husain’s art was neither simply Arab nor Indian, but a blend of disparate, deep-rooted influences that created “a narrative that speaks across cultural boundaries”, Mohammed says. “Even his works that are deeply Indian in spirit are universally resonant and showcase the full range of Husain’s artistic language.”

In the end, he only completed around 35 works from the Arab Civilisation series, working feverishly in his new home in Qatar in the last years of his life. “He always said he was fighting time,” Pundole says. “He had a lot to say and a very limited time to say it.” The art adviser Mehreen Rizvi-Khursheed, who visited Husain in Qatar, tells The Art Newspaper that she found a man in subtle internal conflict. “I found him feeling comfortable and secure to carry on working in peace,” she says. “But he was still pining for India.”

The move to Qatar coincided with the final refinements of Husain’s late style. In the 1980s, he had moved away from “thick impasto” to “flat blocks of colour juxtaposed around each other”, Pundole says. “I asked him why and he said, ‘It’s very easy for me to romanticise an image with thick paint on the canvas, so this was a new challenge to me.’” The development of a new visual style went hand in hand with a willingness to tackle self-consciously big themes, particularly after he became the subject of fevered controversy in India. He began to experiment with new forms of storytelling, immersive environments and public engagement.

Husain’s painting Yemen (2008) Khalid Abdulrahman/© Qatar Foundation

In works from this time, Husain’s expressive power comes through in the interaction of forms, each representing one of the major strands of belief in the world. “The Gulf’s landscapes, heritage and cosmopolitan energy inspired recurring motifs of horses, deserts and the idea of ‘home’”, says Mohammed,

who describes works like the enormous, immersive multimedia installation of 2009, Seeroo fi al Ardh(a Quranic phrase meaning “travel through the Earth”) as “among his most ambitious”.

In one of the galleries in the Doha museum, The Eternal Muse, visitors are asked to consider the figure of the horse. You see, again and again, the same angular, jutting necks and manes and the jaws taut with raw animal energy, recurring in Husain’s work over the decades. In an early work like Doll’s Wedding (1950), the horse signifies something of the cultural identity of India. But, when you stand in front of the enormous, monumental canvas The Battle of Badr, which Husain painted in 2008, at the age of 95, you begin to sense that he moved beyond India: fragmented strands of Kufic script burst forth from the clash of galloping war horses like shrapnel from an explosion. Here, in Doha, the new museum has captured Husain’s final, vital burst of artistic energy.