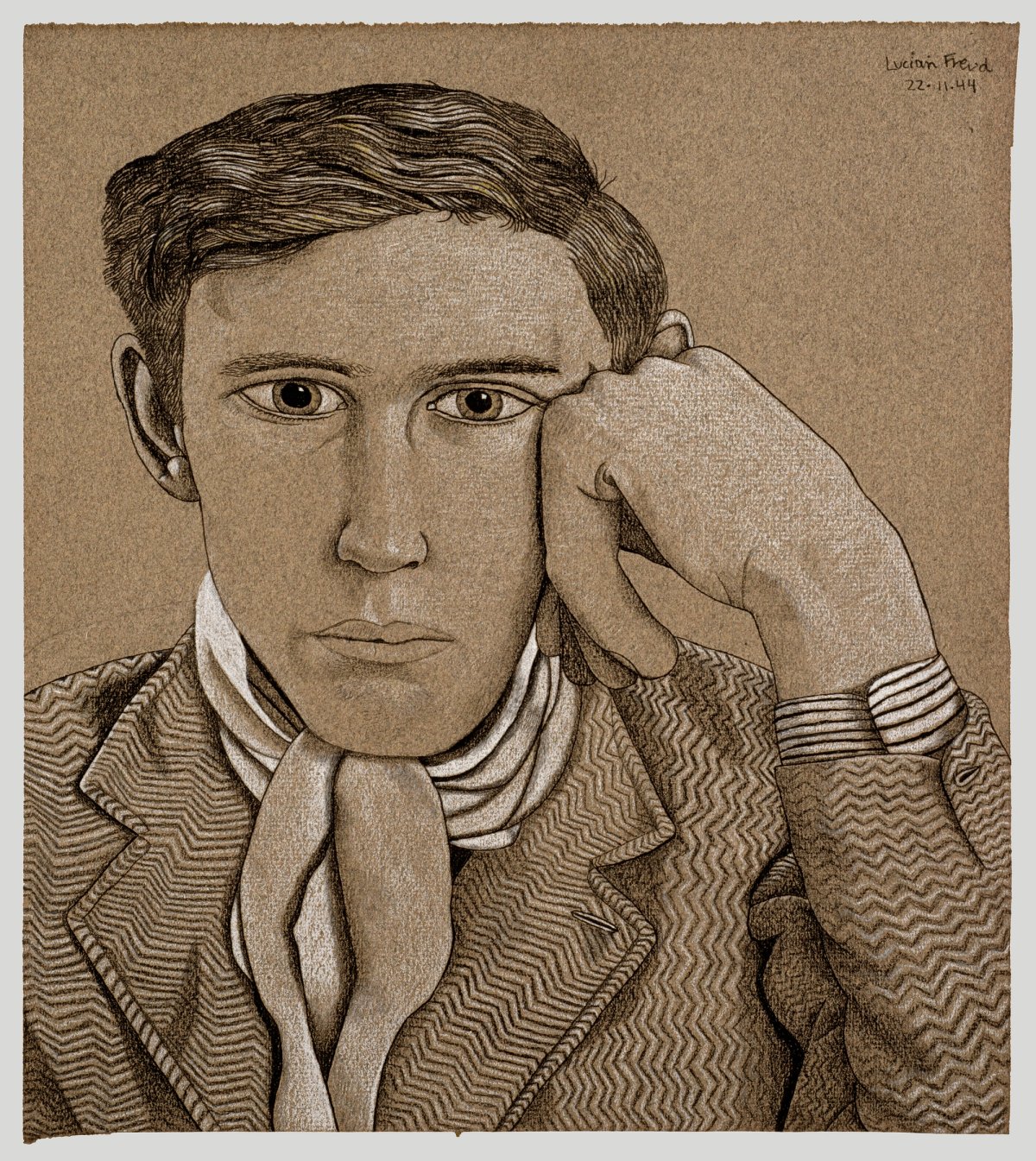

Further proof of the unflagging appetite for Lucian Freud exhibitions comes this month as the National Portrait Gallery (NPG) in London opens the UK’s most significant survey of the artist’s works on paper to date, in an exhibition of 170 drawings, etchings and paintings.

One of the great figurative artists of the 20th century, Freud (1922-2011) topped The Art Newspaper’s 2019 survey of the contemporary artists most frequently exhibited in London since the turn of the century. The trend has continued with exhibitions such as the National Gallery’s Lucian Freud: New Perspectives and the Garden Museum's Lucian Freud: Plant Portraits, which both opened in 2022.

If saturation point is looming, it is not here yet. “For anyone who thinks they know Freud’s work, this exhibition is an opportunity to discover a less familiar, more intimate view,” says Sarah Howgate, who has co-curated the NPG’s new show with David Dawson, Freud’s studio assistant from 1991 to 2011 and now the director of the Lucian Freud Archive.

Acquired by the NPG after Freud’s death in 2011, the archive presents a rich and plentiful supply of new material, augmented by the acquisition in 2024 of 12 works from the artist’s estate, among them eight etchings, which are the first by Freud to enter the gallery’s collection.

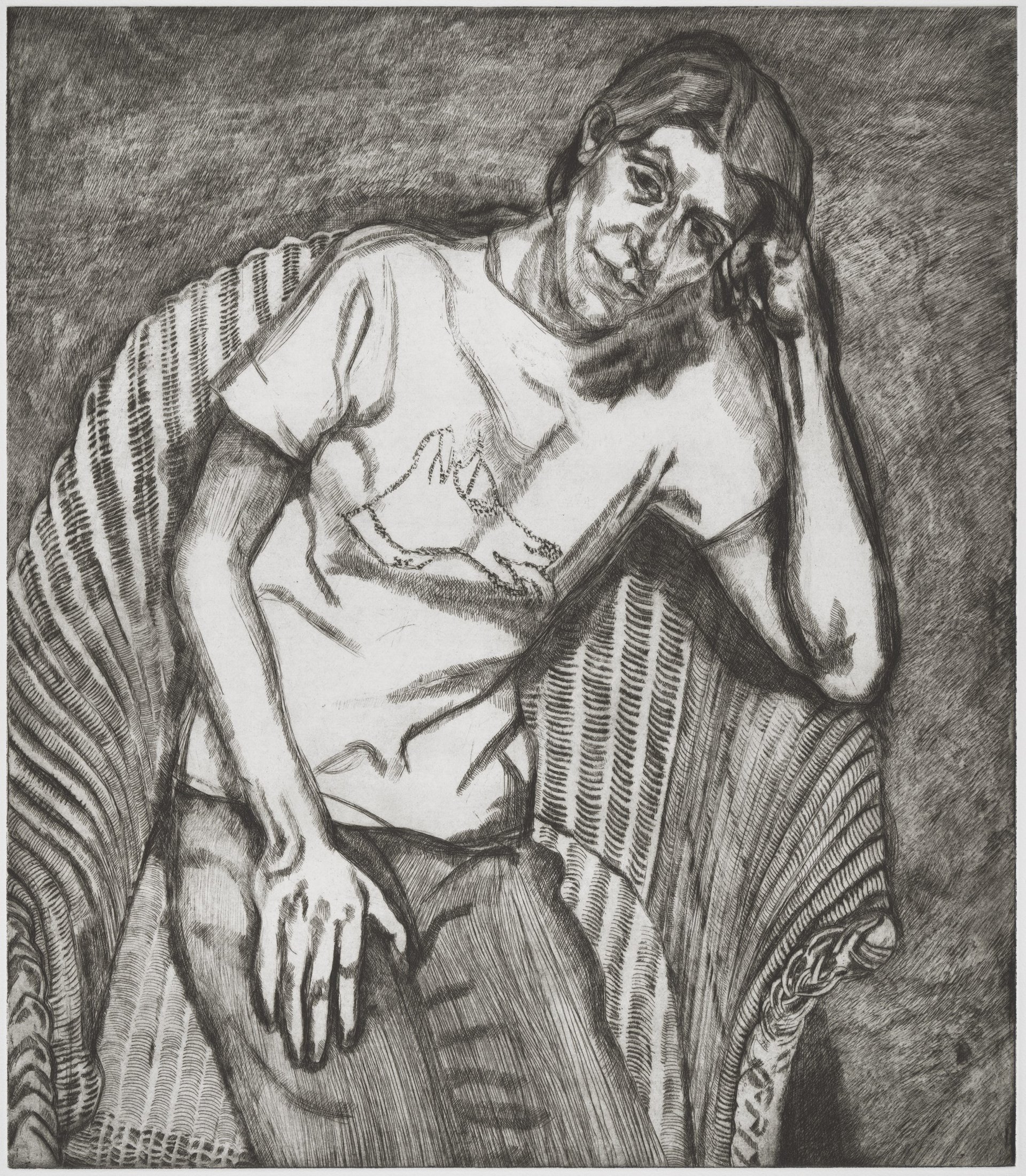

Freud's 1995 etching Bella in her Pluto T-Shirt © The Lucian Freud Archive. All Rights Reserved [2025] / Bridgeman Images. Collection: National Portrait Gallery

Comprising 48 sketchbooks, unfinished paintings, childhood drawings and letters, the archive materials “reveal the artist’s thought processes in a way finished paintings cannot”, Howgate says.

The evidence of his sketchbooks dispels the myth that Freud gave up drawing in the 1950s as his focus shifted to painting. Instead, Howgate writes in the catalogue, “for the following 20 years or so, drawing became a backdrop to his painting, a more private activity in sketchbooks, which recorded the ebb and flow of his life behind studio doors and his daily thinking as an artist.”

Annotated with phone numbers, betting tips, drafted love letters and appointments, Freud’s sketchbooks emphasise not only the biographical nature of his practice but the importance he attached to drawing as a fundamental means of communication. From youthful sketches in crayon, to the tattoos he administered during his time in the merchant navy, to the etchings of his later years, Freud’s drawings were a constant, if shifting, activity that captured aspects of his relationships with wives and girlfriends, children, pets, friends and fellow artists.

“The exhibition is an exploration of how drawing remained central to Freud’s practice throughout his working life and how some of the most significant changes in his art can be traced through his work on paper”, Howgate says. The drawings parallel the development of his painting style, with the austere linearity of his early work giving way to a more painterly approach, echoed in the pencil and charcoal drawings of the 1970s, and his etchings, which, he said, he wanted “to work like paintings”.

Lucian Freud’s oil painting Girl in Bed (1952) © The Lucian Freud Archive. All Rights Reserved 2025 / Bridgeman Images. Photo: © National Portrait Gallery, London. Lent by a private collection, courtesy of Ordovas

At points in the exhibition, drawings will be shown alongside paintings, highlighting their function not just as a preparatory stage but as a means for discovering and developing ideas. Such juxtapositions “demonstrate how Freud used drawing as a way of forensically observing his subjects”, Howgate says. The traces of charcoal underdrawing in his unfinished painting, Last Portrait (1974 -77), show the merging of these two aspects of his practice.

Elsewhere, the drawings he made following his Large Interior, W11 (after Watteau) (1981-83) reverse the process and instead show him honouring, and subverting, the influence of Jean-Antoine Watteau, one of several artistic antecedents.

• Lucian Freud: Drawing into Painting, National Portrait Gallery, London, 12 February-4 May