Bangkok has launched its first biennal (until 3 February 2019) with an international schedule of artists showing at diverse venues around the city. “We’ve wanted this for a very long time,” says artistic director Apinan Poshyananda.

Working with four other curators, Poshyananda has placed the work of 75 artists from 33 countries in 20 venues across the city ranging from museums and galleries to heritage sites, Buddhist temples along the Chao Phraya river, as well as shopping malls, hotels and banks.

This is a biennial that explodes into the city, claiming commercial and sacred spaces alike, to explore notions of happiness (the title of the show is Beyond Bliss). “We wanted to ask artists what is their view of happiness and bliss against the backdrop of a world full of chaos and drama,” Poshyananda says.

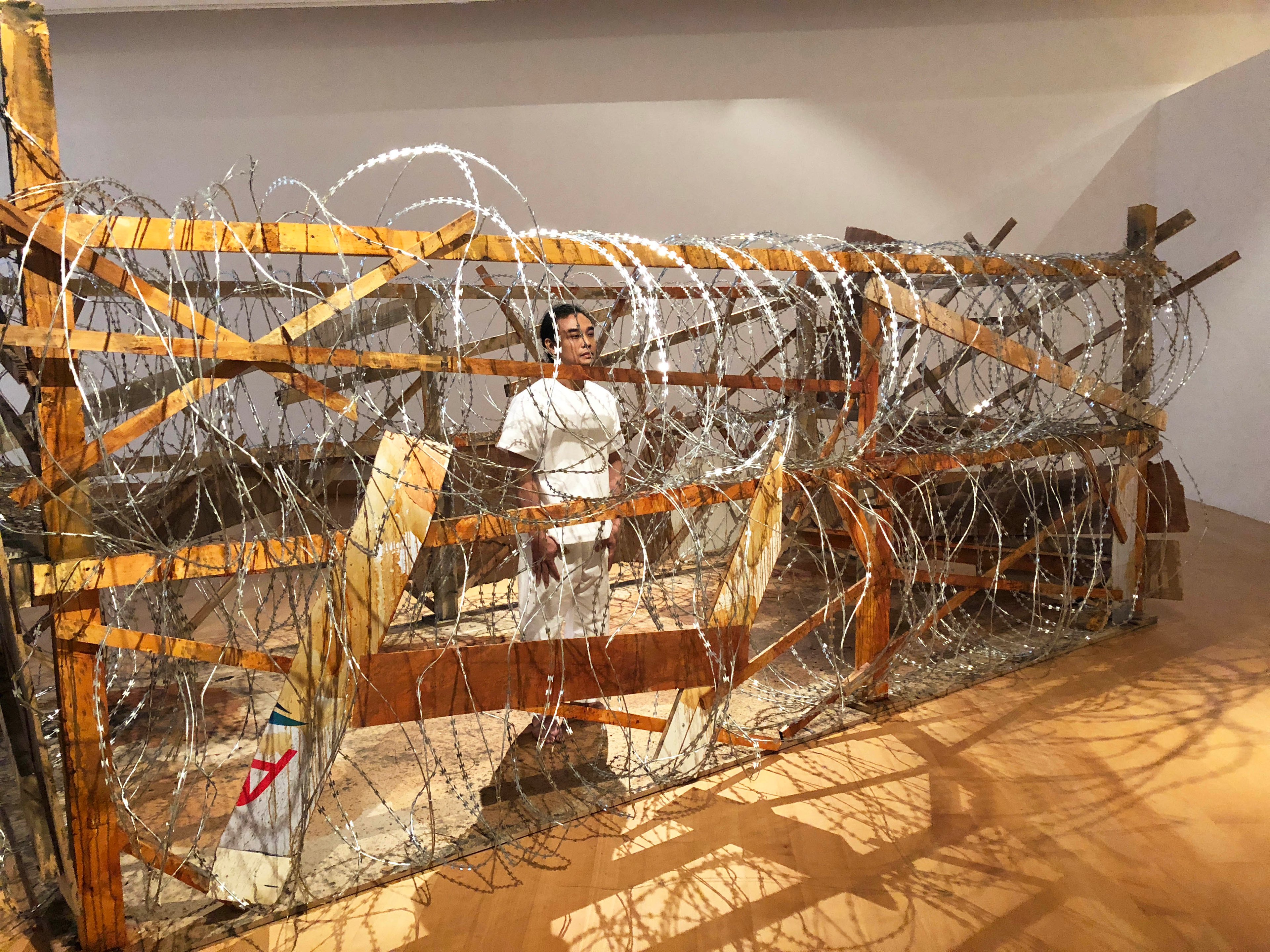

The artists’ responses range from meditative, inward-looking reflections to examinations of political displacement, gender, race and discrimination. A strong focus on female artists and labour runs through the show and there are also works focusing on present political crises, such as the plight of Rohingya refugees living in Bangladeshi camps. “For many artists, happiness is simply a life without violence,” Poshyananda says.

Poshyananda and his collaborators have managed a rare feat by organising an exhibition that is both exuberant and tightly curated. Too many biennial directors choose topics that are too lofty or vague, then display art that bears no discernible relation to their stated themes. But here, nearly every work seen by The Art Newspaper clearly engages with the exhibition’s central question.

Around half the exhibiting artists are from outside Thailand: there are major works from the Scandinavian duo Elmgreen & Dragset, the Korean artist Lee Bul, the Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama, the Russian collective AES + F and the France-based Chinese artists Huang Yong Ping and Yan Pei-Ming, among others. “We did not just parachute artists’ work here for the show—many came in advance and we had talks and discussions with them,” Poshyananda says. “We’ve tried to learn the lessons of other biennials but to create something entirely distinctive and specific to this context,” he adds.

There are also eight performances taking place in the opening weeks of the biennial (until 11 November) under the aegis of the Marina Abramovic Institute. “[Abramovic] was the first artist I asked to participate and the first who said yes,” Poshyananda says. In the biennial’s first week alone, nearly 20,000 visitors attended these performances at the Bangkok Art and Culture Center (BACC), one of the biennial’s main venues. “There is an enormous appetite for contemporary art in Bangkok,” Poshyananda says.

More importantly for the development of the local art scene, the work of around 34 Thai artists and groups is also on display, including pieces by the Muslimah Collective, five young Muslim female artists from the south of Thailand whose work reflects on both the ongoing Islamist violence that blights the region as well as the daily lives of ordinary people. Should the biennal succeed, it is likely to become the flagship event for the country’s contemporary art sector.

Who pays?

This year, biennals in Montreal and Marrakech have been cancelled for lack of money (the organisation that runs the former filed for insolvency in February while the latter event is heavily in debt). To avoid this fate, Poshyananda has worked hard to ensure that there will be at least three editons of the Bangkok Art Biennale and has already secured funding for the next two editions in 2020 and 2022 from corporations including the lead sponsor ThaiBev, one of Southeast Asia’s largest beverage companies.

The inaugural edition was funded with corporate donations of $67m in both cash and kind (numerous hotels such as the Peninsula, the W hotel and the Mandarin Oriental offered free hotel rooms), making this biennal not just a curatorial achievement but also a fundraising one, particularly impressive in a country with little government money for the arts. “We want to make this sustainable and we hope this will evolve into a long-term exhibition,” Poshyananda says.