The Abstract Expressionists have gone down in art history as a macho band of hard-drinking, paint-flinging American heroes, channelling their angst into monumental masterpieces of abstraction. The US poet Frank O’Hara called this “the art of serious men”. For too long, the women who forged a radical new painting style alongside them were marginalised and forgotten.

Only recently are painters like Grace Hartigan, Elaine de Kooning and Lee Krasner being recognised and reassessed. London’s Whitechapel Gallery is expanding the canon further still with Action, Gesture, Paint: Women Artists and Global Abstraction 1940-1970, an ambitious international survey celebrating a generation of women who helped to redefine art in the wake of the Second World War.

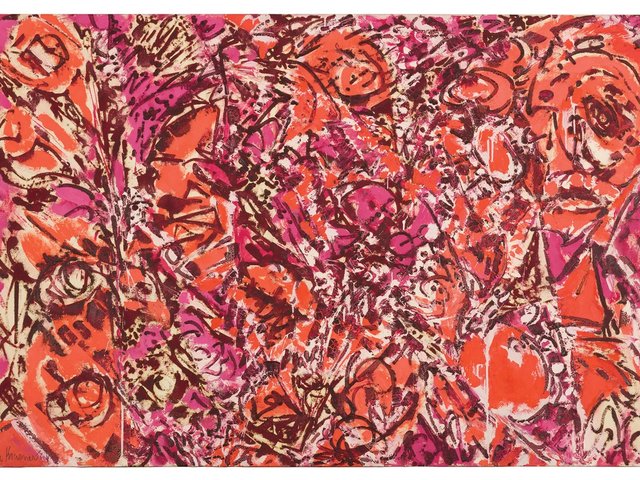

Behjat Sadr's Untitled (1956) Courtesy of Behjat Sadr Estate. © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2022

The selection of more than 150 paintings by 80 artists orbits Abstract Expressionism but demonstrates how the movement’s experimental spirit travelled and evolved far beyond US borders. Living through tumultuous post-war times, artists from Europe, East Asia, the Middle East and Latin America searched for “a new way to represent the world” through an abstract language of “subjectivity and feeling, self-expression and release”, says Candy Stobbs, the exhibition’s co-curator. “These artists were not necessarily known to each other at all,” she stresses, “but there seemed to be a zeitgeist in the air.”

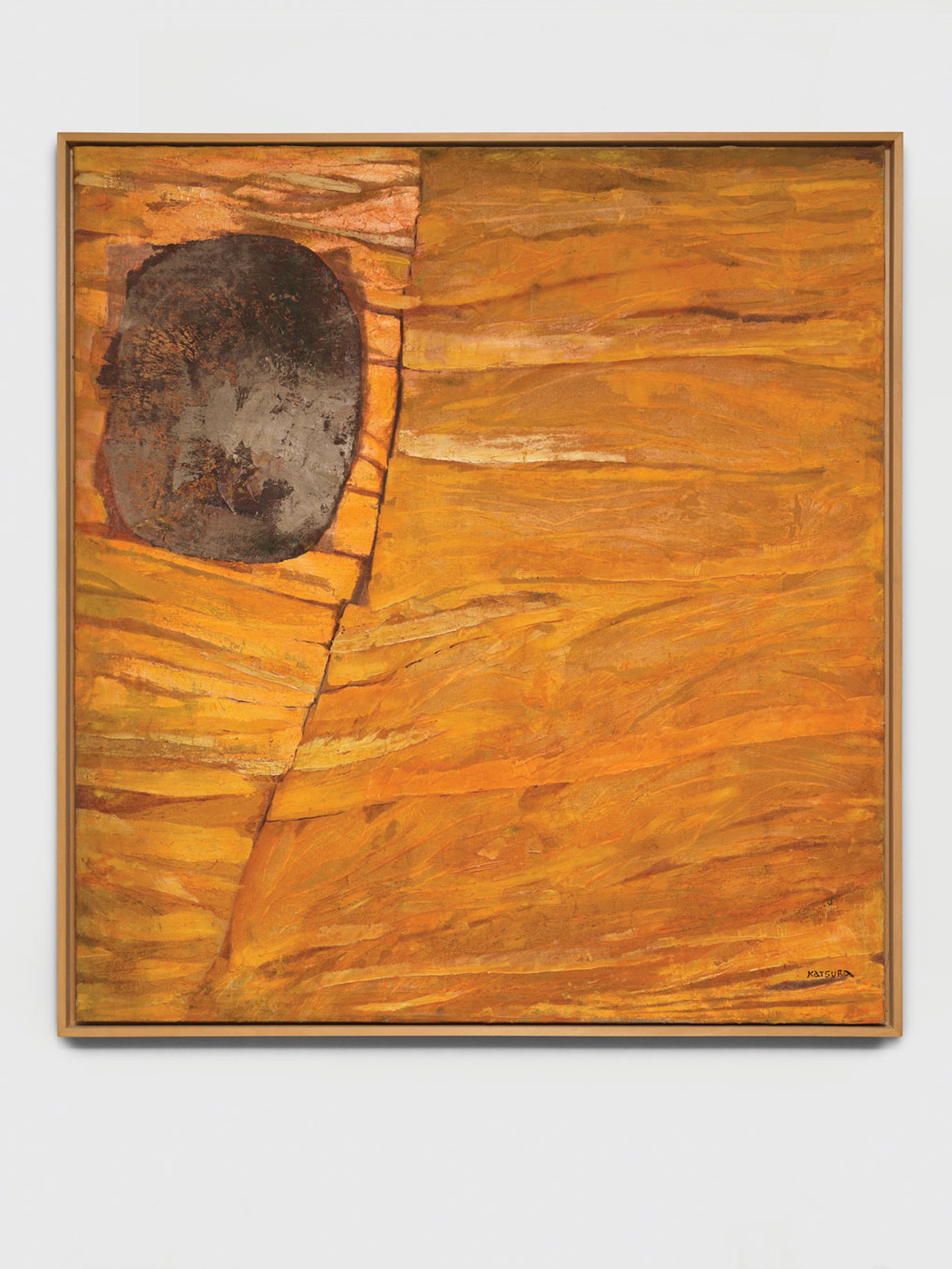

That zeitgeist gave birth to a dazzlingly diverse range of painting practices. Helen Frankenthaler laid down raw canvas and soaked it through with gauzy, intense colour fields. The Iranian artist Behjat Sadr also took to the floor, abandoning the easel and brush for palette knives and scrapers. The Argentinian painter Sarah Grilo’s graffiti-like scrawls, inspired by the streets of New York, are a “precursor of Basquiat”, Stobbs says. While Japan’s Yuki Katsura added delicate textures to her works with collaged layers of washi paper, the Venezuelan artist Elsa Gramcko incorporated sand, glue, cement and scrap metal, and Peru’s Gloria Gómez-Sánchez attacked the picture surface with fire and acid.

Yuki Katsura's Work (1959) Courtesy of the collection of Melissa M. Stewart, New York, NY © Estate of Yuki Katsura

If this was an art form dedicated to plumbing the depths and expressing the self, it also had a political edge. Gramcko’s rough materiality has been read as a response to political unrest unfolding in Venezuela. In Poland, Erna Rosenstein made biomorphic landscapes defying the dictates of Soviet socialist realism. And Bertina Lopes was heavily engaged in her native Mozambique’s struggle for independence from Portuguese colonial rule.

Simply by pursuing careers as professional artists, these women were pushing against society’s expectations, Stobbs points out. “Gender parity was something that didn’t exist at all, and I think they all struggled.” Michael (Corinne Michelle) West, for instance, adopted a male pseudonym to avoid discrimination in the New York art world. The self-taught Ukrainian American artist Janet Sobel, who made pioneering drip paintings a year before Jackson Pollock, was dismissed by the critic Clement Greenberg as a “primitive” and a “housewife”, and is only now being rediscovered.

Janet Sobel's Illusion of Solidity (around 1945) Courtesy of ASOM Collection

Perhaps it is no coincidence that many of these artists embraced a gestural, bodily process. They sought freedoms of all kinds: to work, to paint, to make their mark on the world. De Kooning may have summed it up best when she said: “A painting to me is primarily a verb, not a noun, an event first and only secondarily an image.”

• Action, Gesture, Paint: Women Artists and Global Abstraction 1940-1970, Whitechapel Gallery, London, 9 February-7 May; Fondation Vincent Van Gogh, Arles, 3 June-22 October; Kunsthalle Bielefeld, 2 December-3 March 2024