Nothing sits still in Jan van Kessel’s pictures. Dotted with amber-flecked beetles and marbled moths, the Flemish painter’s oils stir with life. In them, butterflies—some lemon yellow, others pearl grey and daubed with green—perch on rosemary leaves. Velvety bumblebees tiptoe over paper-thin blossoms. If insects, as the English naturalist Thomas Moffett wrote in 1590, are for the “delight of the eyes” and the “pleasure of the ears”, then these pictures are pure joy.

Arrayed in the National Gallery of Art show Little Beasts: Art, Wonder and the Natural World, in Washington, DC, are paintings and prints by Van Kessel and Joris Hoefnagel, among others, from 16th- and 17th-century Europe, when expanding trade routes brought the study of nature—and nature as art—to new heights. In the Flemish port city of Antwerp (its harbour once dubbed the market of “all of the universe”), Hoefnagel and Van Kessel responded to the surge in demand, inflecting their pictures with black- and silver-quilled porcupines, fire-red salamanders and checkered caterpillars, all with a studied delicacy. Here, the minute is monumental.

Hoefnagel travelled widely, fixing his gaze on the small and intricate. As a luxury merchant, he ventured to France and Spain, of which he noted: “He who has not witnessed Seville has not witnessed miracles.” Art lovers in Europe commissioned pictures of their own acquired miracles or cabinets of curiosity. And the curiosity ran deep. Hoefnagel made 300 watercolour miniatures for one series, and Van Kessel’s oeuvre included more than 700 works.

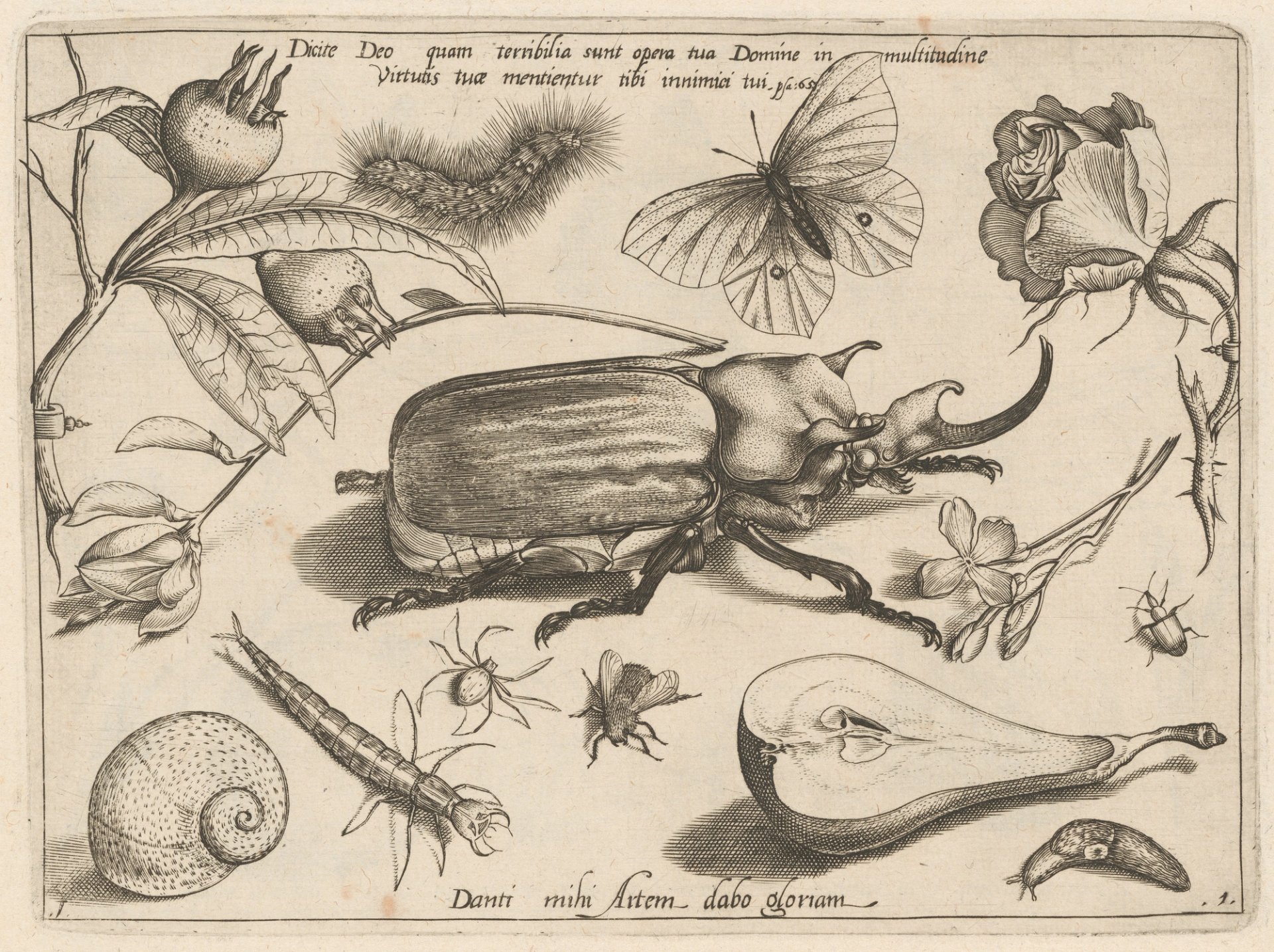

Jacob Hoefnagel (after Joris Hoefnagel), Part 1, Plate 1, from the series Archetypa studiaque (Archetypes and Studies), 1592 Courtesy the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

What is most striking about these pictures, set against the gallery’s pistachio and brick-red walls, is their masterful detail. Hoefnagel works with a surgeon’s precision, drawing out each cell of a dragonfly’s gossamer wing, its lime-green body awash in liquid-black abstraction. To his tortoiseshell butterfly, he added touches of gold; to fish scales, gauzy silver paint. In one picture, Van Kessel signed his name in feverish-red caterpillars and emerald-scaled serpents, jewel-like spiders hanging down, tauntingly, over the painting’s edge.

To be that attentive to nature, to let the world wash over you, seems a particular kind of gift. In the same way one loses the train of a conversation when suddenly fixating on something beautiful, Hoefnagel and Van Kessel seem to linger in the very act of looking. There is a tenderness to this work, an intimacy. “Stay a while,” they seem to urge. “Go on looking.”

Their attentiveness had a spiritual posture too. These pictures were a reminder of divine providence, of God’s grace made manifest. As the English naturalist John Ray wrote in 1691: “If man ought to reflect upon his Creator the glory of all his works, then ought he to take notice of them all, and not think any thing unworthy of his cognizance.”

Time spent observing is never wasted. Consider Hoefnagel’s elephant beetle, sinuous and copper-dappled, its horn curved like a thick eyelash. It sits below an inscription from the Book of Psalms: “The fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom.” It is from that vantage point—low to the ground and seeing the world anew—that these artists delighted in nature and its splendours. The elephant beetle, believed at the time to have originated from its own ashes, evoked Jesus Christ’s resurrection—as did the butterfly, emerging from a cocoon into a state of winged brilliance. (Moffett wrote that the butterfly’s sapphire wings can “shame the peacock”.)

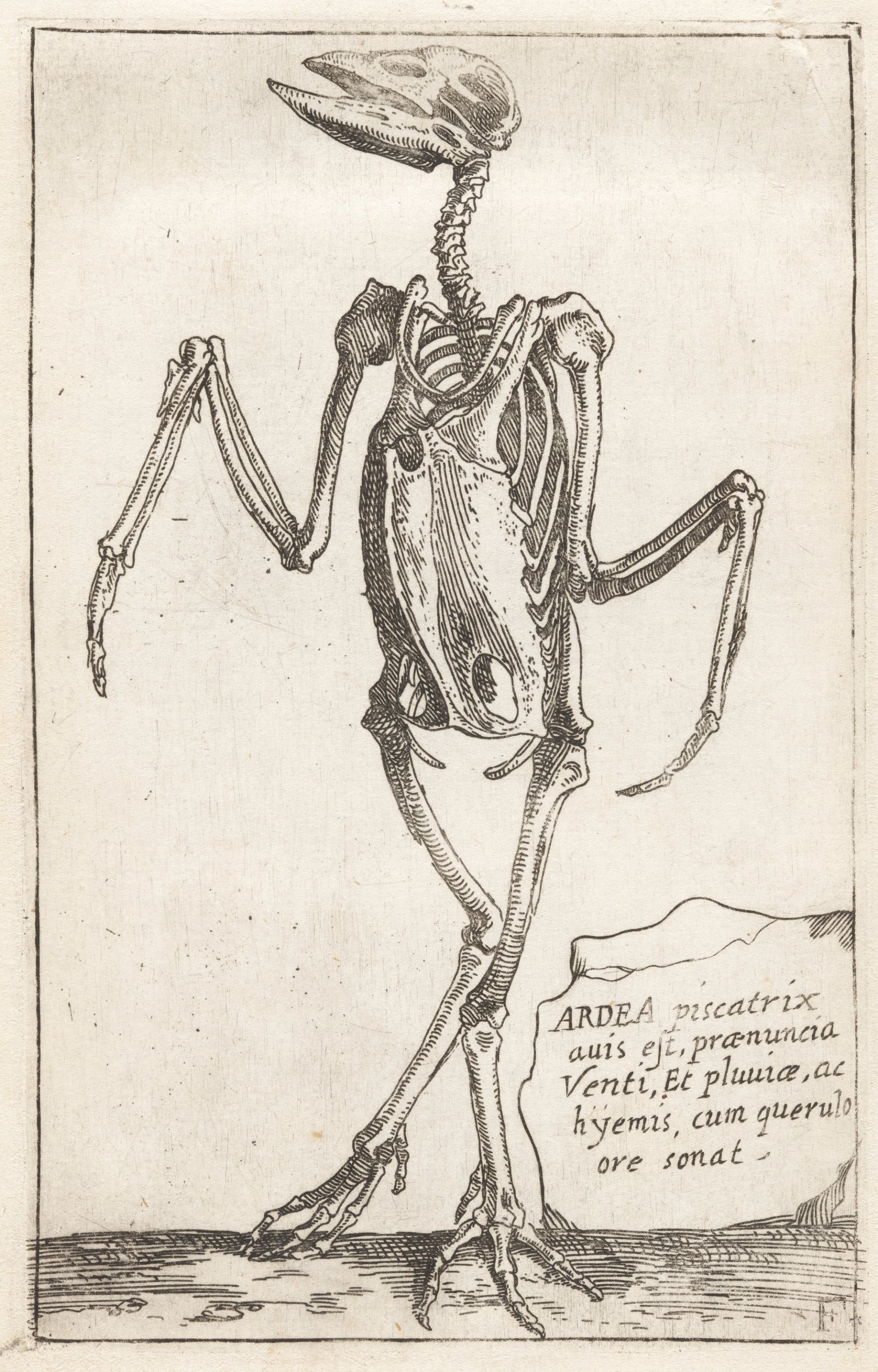

Teodoro Filippo di Liagno, Skeleton of a Heron, from the series Animal Skeletons, 1620–21 Courtesy the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

Shame runs throughout the show, too, tinging it with a pathos that hangs lightly, never feeling like a burden. Take the Neapolitan artist Teodoro Filippo di Liagno’s series of etchings of animal skeletons. One, of a heron, is carefully attended to—its needle-sharp limbs sloped inwards like a ballerina at rest. The memento mori seems weightless, suspended in time. One gets the sense that even the macabre here was done in a spirit of playfulness. As Jacob Hoefnagel, Joris’s son, inscribed on one of his father’s pictures, the work is “freely communicated in friendship to all lovers of the Muses”. Love abounds in all these works.

One of the final pieces in the show is Van Kessel’s Noah’s Family Assembling Animals Before the Ark (around 1660). Strewn with tomato-red parrots and turkeys ringed in charcoal, it is a work of close study, of fear giving way to hope. The flood is at hand, but Van Kessel privileges beauty, unfettered. There will be hardship, it pronounces, but also sublimity, something wondrous and beyond imagination.

The lush essays of the American naturalist John Burroughs come to mind. In one, he recalls the thrill of catching a bee in his hand: “Though it stung me, I retained it and looked it over, and in the process was stung several times; but the pain was slight.”

- Little Beasts: Art, Wonder and the Natural World, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, until 2 November