Charles Richmond, 11th Duke of Richmond, has done something decidedly ambitious in launching the Goodwood Art Foundation, a new non-profit contemporary art centre for the southeast of England, with a strong educational mission. The foundation is set high on the South Downs, in West Sussex, at the heart of the Goodwood Estate that Richmond and his forebears have made, over the past 350 years, into a thriving home for horse racing, motorsport, organic farming and the family’s historic art collection.

Richmond and the foundation have engaged, over the past three years, in a multi-faceted task: the reimagining of a 70-acre plot of meadow and woodland (part of which was formerly the home of the Cass Art Foundation), overseen by the celebrated landscape designer Dan Pearson; the refurbishment of two existing pavilions to 21st-century climate-controlled standards; the building of 24, a new steel-clad restaurant designed by Studio Downie Architects, creators of the original 1990s pavilions; and the devising of a launch season of contemporary art overseen by the independent curator Ann Gallagher, the former director of collections for British art at Tate.

Gallagher’s headline exhibition consists of sculptures new and old by the Turner Prize-winning artist Rachel Whiteread and an absorbing first full-scale show of Whiteread’s photography. Gallagher has also brought together an installation of new work and old—shown across the foundation's landscape and in its galleries and café—by the contemporary artists Rose Wylie, Veronica Ryan, Susan Philipsz, Amie Siegel and Lubna Chowdhary.

The Gallery, the refurbished main exhibition space, in the upper woodland at the Goodwood Art Foundation Photograph by Jonathan James Wilson, courtesy of Goodwood Art Foundation

There are also two pieces by the 20th-century master Isamu Noguchi (1904-88) that bring a playful wit to the Sussex landscape, while later this summer the foundation will unveil the first European presentation of Magic Square #3, a vividly coloured, open-air labyrinth by the influential Brazilian sculptor Hélio Oiticica (1937-80).

The Goodwood Art Foundation’s ambitions

The foundation, which opened on 31 May, has clear aims: to be a home for art as a source of education, inspiration and wellbeing, one without barriers to entry. “I was very keen,” Richmond tells The Art Newspaper, “that we [should have] a proper not-for-profit, with real ambition.” His father, the 10th duke, started an education trust in the 1970s which, Richmond says, is “still going very strongly”. That charity enables more than 3,000 children a year, many of whom have never visited the countryside, to come to Goodwood to discover the rural landscape and to understand where their food comes from.

Bluebells in the upper woodland of the 70-acre site of the Goodwood Art Foundation Photograph by Lucy Dawkins, courtesy of Goodwood Art Foundation

The art foundation, Richmond says, is, in part, “an ambitious extension” of the education trust. “Art, environment and education are the three big pillars,” he says, with “physical, mental, wellbeing, creativity, and all-round learning, all really important parts, coming from those three pillars.”

The foundation aims to show “art in nature … in a very quiet, un-busy but very natural environment”. The sculptures are not being shown in parkland or formal gardens, as at a number of other British country houses, but in a hillside setting where ancient woodland opens on to beguiling vistas across flower meadows and farmland. “It's a very unusual location in this contained environment,” Richmond says. “We want it to be useful in a way to the people that are going to get the most out of it.” Especially, he says, because “there is so little art and music on the National Curriculum [for UK schools]".

Richmond is a devotee of modern architecture, furniture and photography. He is keen, he says, that the foundation "should be seen as a good addition to the contemporary art world". The foundation’s director Richard Grindy adds that Gallagher was determined that the curating should be academically sound and the work on show significant. “Should you be in that top 1% of art lovers or academics, you will look at that and be aware that it is a very important body of work and season of exhibitions,” Grindy says. “But, at the same time, the main bulk of the audience are going to be people that aren't art experts and can walk through the gate … to experience the environment. And if you happen to leave, having enjoyed what you saw from an art point of view, then that's a huge benefit to everyone.” The foundation wants, Grindy says, to “break down barriers, get people learning without even knowing it”.

24, the new café designed by Studio Downie Architects, in the upper woodland at Goodwood Art Foundation Dave Dodge/PA Media Assignments

A landscape in tune with itself

Gallagher and Pearson have worked closely together from early on, seeing the developing landscape as a place where visitors can encounter art in an act of serendipitous discovery. The planting has been planned to allow for 24 two-week botanical highlights across the site and through the year. This spring, newly planted magnolia trees have flowered; the long-established blanket of bluebells has spread itself under the forest canopy; and a grove of cherry has blossomed up against the historic flint wall that snakes elegantly along the rise and fall of the site's northern boundary.

This naturalistic setting for art is named the Schwarzman Gardens in recognition of the backing given by the Stephen A. Schwarzman Foundation, founded by the eponymous chief executive officer of the private equity giant Blackstone.

Even in the first week of the foundation's opening, with decades of development to come as the planting and landscaping matures, it is clear that Richmond's ambitions are already being realised. The close collaboration between Gallagher, Pearson and the featured artists is bearing fruit. The art feels in tune with itself and with the landscape. There are arresting and unexpected moments of discovery, natural and artistic, to be encountered in walks through the woods and into the downland meadows.

Rachel Whiteread, Untitled (Pair) (1999), in the upper woodland by the chalk pit at Goodwood Art Foundation Photograph by Lucy Dawkins, courtesy of Goodwood Art Foundation

The first source of delight is the clarity with which Gallagher, Whiteread and Pearson have defined the separate sections of the site, and the areas of transition between them. It is in those border areas, the debatable land, the liminal space at the forest's edge—so freighted with folkloric significance and carrying the sensory charge of changing light conditions—that much of the curatorial magic happens.

A voyage of discovery

A visitor to the foundation arrives at the site's highest point, in a spreading plantation, where tall, close-planted trees have been thinned in places and thousands of bulbs planted in readiness for next spring. The foundation’s three buildings stand at the east end of this area, with an open-air amphitheatre, to be used for school gatherings and performances, sited at its western extremity.

This “reception” area will be the site of the foundation’s educational activities from September. To its south lie, on one side, an area of ancient coppiced woodland, bisected by a grid of forestry access paths, and on the other a light-filled expanse of flower meadow that acts as the final quarter of the foundation's layout.

Looking south from the expansive cantilevered terrace of the 24 café, Whiteread’s Down and Up (2024-25)—a striking new work in blue-grey concrete representing a cast of a two-flight staircase—can just be made out at the near, top, end of the meadow, largely concealed from this vantage point, at the artist's request, by the sap-green late spring foliage.

Isamu Noguchi, Octetra (three-element-stack) (1968/2021), at the border of the upper woodland and the flower meadow at the Goodwood Art Foundation Photograph by Lucy Dawkins, courtesy of Goodwood Art Foundation

At the south margin of the main plantation, at its border with the meadow, openings have been made to present the warm blancmange-blush-painted bronze of Wylie’s jaunty Pale Pink Pineapple/ Bomb (2025) and the vivid poppy red of Noguchi’s Octetra (three-element stack) (1968/2021). The pigments of both pieces “pop” against the surrounding green and a theatrical backdrop of hedgerow-lined farmland spread across Prussian-blue hills.

Looking east from the café terrace the viewer takes in another work by Whiteread: Untitled (Pair) (1999), two sarcophagi-like pieces, whose white painted bronze solidity is luminous against the surrounding verdant grass. Visitors then follow a path that winds round an old chalkpit to encounter a pair of Ryan’s works—Untitled (Magnolia Pod) (2024) and Magnolia Blossoms, (2025)—two beautifully scaled bronze pieces inspired by the foundation’s recently planted magnolia trees, each work set on circles of matting, flanking the path like grand-scale votive offerings.

Veronica Ryan, Untitled (Magnolia Pod) (2024, top) and Magnolia Blossoms (2025) in the upper woodland at Goodwood Art Foundation © Veronica Ryan. Photo by Lucy Dawkins, courtesy Goodwood Art Foundation. Magnolia Pod, Collection of Lorenzo Legarda Leviste and Fahad Mayet

A rich concert of birdsong

Deep in the ancient woodland, Pearson stops to explain how each of the quadrants of coppice will be taken down in rotation, every eight years, to encourage biodiversity by letting “the light back down to the forest floor and [allowing] all those cycles that happen in nature when a tree comes down impose themselves back into this space.” He points out the full harmony of late spring birdsong which “comes when you get good balanced biodiversity”.

That rich concert of birdsong provides a moving background to another liminal art experience—As Many as Will, a haunting sound installation of four overlapping vocal recordings of 16th-century country dances created by Philipsz —as the listener stands encircled in a felicitous mix of chanting human voice and liquid, fluting, birdsong. The piece has been set up in the final stretch of deep-shaded forest looking out to a path mown through the flower meadow where the foundation plans a body of water in future, Pearson says, “to bring the sun down to the ground”.

Rachel Whiteread, Down and Up (2024-25), in the flower meadow at Goodwood Art Foundation Photograph by Lucy Dawkins, courtesy of the Goodwood Art Foundation

A visitor who goes out into the meadow after being immersed in As Many as Will—from enchanted forest to Elysian fields—will catch sight, in the distance, at the far end of a long, gentle, rise, of Whiteread’s Down and Up. Its blue-grey V-shape stands proud against the backdrop of the June foliage of the upper plantation, its two-storey bulk dwarfed, as the artist tells The Art Newspaper, by the grand scale of sky, trees and meadow.

It is a visual moment that captures the skill and intention with which Gallagher, Whiteread and the other artists have placed each work in its own distinct space, to encourage audience engagement on the work at hand, without competitive distraction from another exhibit. It is an intriguing, beckoning, sight that encourages the visitor to walk up the slope to examine the piece's special disposition, tipped through 90 degrees. "I am interested," Whiteread tells The Art Newspaper podcast The Week in Art, "in changing things slightly and making them slightly strange."

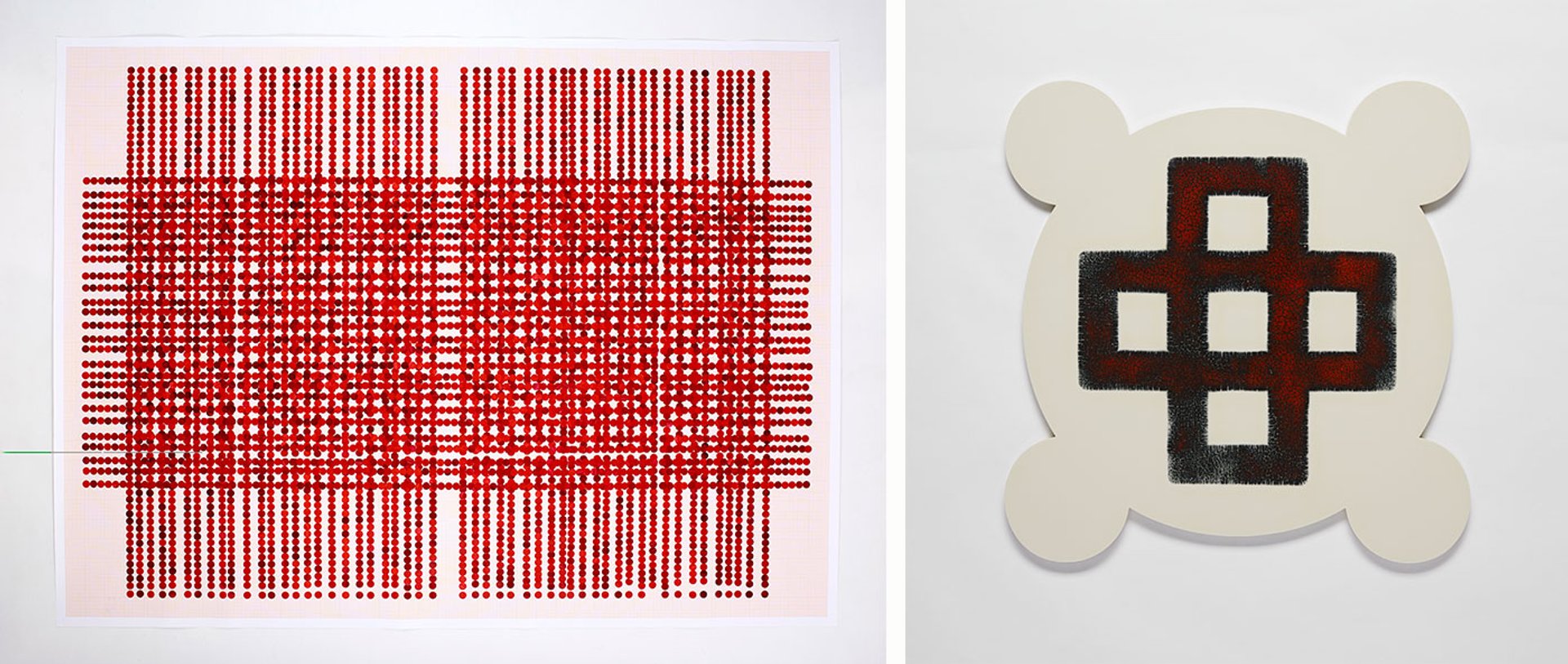

Back in the woods, Gallagher is showing three artists in the foundation’s three buildings. Works by Lubna Chowdhary on the walls of the 24 café include two pieces, the drawing Series 4: Number 2 (2022) and the ceramic tile Marker 62 2023. In the Pigott Gallery—the smaller of the exhibition spaces—is Amie Siegel’s film Bloodlines (2022), a meditative account of the works of George Stubbs being prepared, in houses around the country (including Goodwood), for loan to the Stubbs exhibition All Done from Nature (2019-20) at the MK Gallery in Milton Keynes.

Two pieces by Lubna Chowdhary on show in the foundation's 24 café: Series 4: Number 2 (2022), left, and Marker 62 (2023) Courtesy of the artist and Jhaveri Contemporary

An appeal to emotion

In the main gallery is an installation—two sculptures by Whiteread and a revelatory show of her photography—that can be visited and revisited as either the beginning or end of the artistic, and emotional, journey of the Goodwood Art Foundation’s first season.

In the smaller space are 12 pieces from Bergamo III, carved in three types of marble local to that north Italian city to represent the space under the seat of wooden kitchen chairs, leaving the negative space to express legs and crossbars. The carvings reflect Whiteread’s feel for geology (the ancient local stone) and of creating work that epitomises human connection to objects, in this case the act of sitting. They derive from a larger such installation commissioned by Galleria d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea di Bergamo in 2023 which acted as a source of meditation and healing for inhabitants of the city three years after it had found itself at the harrowing epicentre of the Covid-19 pandemic when it first arrived in Europe in early 2020.

Rachel Whiteread's Doppelgänger (2020-21) on show in The Gallery at the Goodwood Art Foundation in West Sussex, surrounded by an exhibition of the artist's photographs Dave Dodge/PA Media Assignments

In the larger space, Whiteread is showing prints of photographs taken over three decades, in work that she describes as a sketchbook for ideas, largely taken on her travels, using a series of cameras including a beloved Nikon, multiple lenses and more, and, more recently, a high-specification iPhone.

Whiteread gave Gallagher access to her archive of thousands of images, ranging from slides to digital files. After Gallagher had produced a long-list of a thousand or so images, Whiteread worked with her on selecting the final groupings. The photographs, Whiteread tells The Art Newspaper, are of multiple subjects—on the streets, inside museums and galleries or out in nature—but they are “normally to do with some sort of haphazard intervention by humans”.

Rachel Whiteread, Carmarthenshire, Wales 2021 and Carmarthenshire, Wales, 2020 (2025) Photograph, Chromogenic print. © Rachel Whiteread, Courtesy Gagosian

The finished chromogenic prints are presented in pairs, encircling the brilliant white, shed-sized sculpture, Doppelgänger (2020-21), a representation of structural collapse in corrugated iron, beech, pine and oak. A pair of photographs of a rusting caravan consumed in undergrowth and a collapsed house whose sagging roof is kept up only by a full-height refrigerator, are nicely placed directly opposite Doppelgänger and its caved-in corrugated iron roof. Whiteread, speaking to Gallagher for a catalogue interview, reflects on the sense of discord that exists both in her sculptures and her photographs. “Discord is part of life and we are living in a period of history that is far from harmonious,” she says. “But nature always has the capacity to be destructive and yet somehow eventually heals the earth.”

Whiteread notes how Goodwood is best known for its annual motorsports events, Festival of Speed for high-performance cars and the Goodwood Revival for mid 20th-century cars, which Richmond has developed on the estate over the past 30 years. The art foundation, she says, is something “more bucolic and quiet … something that you can see all year round. It's not just a weekend or bank holiday event. I think it will really add to … [this] part of southeast England.”

Rose Wylie, Pale-Pink Pineapple/Bomb (2025), at Goodwood Art Foundation Photography by Lucy Dawkins, courtesy of Goodwood Art Foundation

Richmond tells says that he wants visitors to the Goodwood Art Foundation to have a great experience, one that touches them through sensory experiences with art and nature as part of a health-giving process that leaves them mentally uplifted.

The carefully spaced and separated moments of artistic theatre and emotional discovery that Pearson, Gallagher, Whiteread and all the contributing artists offer at the foundation's first public offering, in this bewitching landscape, are a reminder of the complete delight, the sense of complete focus, that encountering art can generate. It brings to mind a telling remark that the august art critic Bernard Berenson once made to the historian Iris Origo as they wandered through the Tuscan hills a century ago. “One moment is enough,” Berenson said, as he spoke of the art of looking, “if the concentration is absolute”.

• Goodwood Art Foundation, West Sussex, UK, is open Thursday to Monday; 9am to 5pm, until 2 November; 10am to 2pm, 3 November to 31 March. Adults £15; students and green travellers £10; children under 18 free. Car parking booked in advance.

• Rachel Whiteread is at Goodwood Art Foundation until 2 November. Presented in partnership with Rolls-Royce Motor Cars.