The Jamaican British theorist Stuart Hall called cultural identity “a matter of ‘becoming’ as well as ‘being’”, a nod to the duality of post-colonial existence. The artist Nickola Pottinger takes this dichotomy head-on in her first solo museum exhibition, fos born, on view at the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum in Ridgefield, Connecticut and curated by the institution's chief curator Amy Smith-Stewart.

Pottinger’s emotive, organic sculptures, totems to her Jamaican heritage and West Indian upbringing in the Crown Heights neighbourhood of Brooklyn, implicate the viewer in their own “matter of 'becoming'”—fraught, ferocious undertakings filled with old magic and new perspectives.

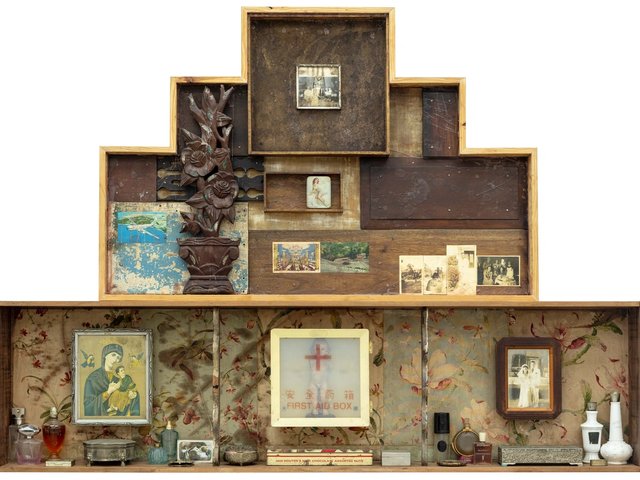

She calls these figures duppies, a reference to the chimeric, night-walking spirits of Jamaican folklore, and constructs them from furniture, bones, bird cages, gilded Yagua leaves and a panoply of other recycled materials that toe the line between trash and treasure. Her creatures are draped in pigmented paper pulp that Pottinger creates from family documents, rubble and first drafts using her mother’s handheld kitchen mixer, yet another layer in the personal and cultural palimpsest of her practice. Pottinger’s ghosts have a presence that’s both unsettling and hypnotic, inviting viewers into her history.

Fos born draws on the recent birth of Pottinger’s daughter, Zora, as its thematic centrepiece. The marvelously lumpy Give tanks and praises (2025) incorporates a cast of the artist’s pregnant torso, positioning the act of human creation as both a tender and carnal process.

This sculpture is one of a collection of brand new works paying tribute to motherhood that the artist created specially for the exhibition. Whether hanging from the wall, sitting on a pedestal or lying on the floor, Pottinger’s humanoid reliquaries find familiarity in the seemingly unknown, braiding disparate narratives together into talismans. There is a flux to these sculptures, a sense that their “becoming” could happen at any moment and in any anarchic fashion. Part of this tension lies in Pottinger’s penchant for line—originally trained in drawing, not in sculpture, she developed a highly personal, speculative procedure for her duppies, lending them a singular, haunting quality.

The Art Newspaper caught up with Pottinger to talk ghosts, spirits and childhood bedrooms.

Installation view of Nickola Pottinger: fos born at the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, until 11 January 2026 Courtesy of the artist and Mrs. © Nickola Pottinger. Photo: Olympia Shannon.

The Art Newspaper: Are you thinking about how these figures talk to each other in the galleries while you’re planning a show?

Nickola Pottinger: This was actually my first time really placing the works for an exhibition of mine. Previously, I made the work, and then the gallerist and I would just set it up. This time, [Aldrich chief curator Amy Smith-Stewart] and I sat down with a floor plan I had drawn out and my husband printed images of each of the individual works and we mocked it up; we wanted to make sure that it had a sense of the narrative throughout the three rooms in which the works are shown.

There’s some older work in there—the genesis of the practice that began as a wall relief was from a show in 2022. We were trying to be very thoughtful about how the work has evolved over time and how to highlight the way themes and materials reappeared throughout the work. Even the placement of the work—for one of the larger sculptures, there are drawings on the surface that mirror the gestures of the physical sculpture that's diagonally across from it.

It all happened intuitively. I don't go into a work saying, “I'm going to make a goat.” I learn and make through using my hands. There's a channeling process as I'm working that takes me to another place. And so I'm always rewarded with this surprise, this gift in the end. I would say 75% of the way through the work, I have a better understanding of the direction in which I'm going. And then there's an editing process that happens as well where I'm building, but then also breaking it down physically, either throwing the work or breaking the work and building it again.

When you talk about making as a form of editing, is there a sense of regeneration in the work? How does that impact the way we’re encouraged to think about these figures?

I come out of a strong drawing practice and have drawn for several years. I always wanted to explore sculpture, but was intimidated by it, and never took it in school, probably because it was the most expensive class and it was always mostly men taking the class. I kind of graduated from making these collage works, which I made according to the same principles as I described. It's always breaking and building. In a paper format, I was tearing and cutting up my own drawings and building these surfaces and textures. They were quite massive and quilt-like. It still used a lot of some of the materials I use now, like oil pastels and watercolours.

During the pandemic, when I was home and I was spending much more time with family who also lives nearby, we would get together in our backyard and we would tell stories. I would go to my family home and collect things that were in my sisters' and my room growing up. We still have book reports and ceramics that we made in high school. I had basically foraged my childhood bedroom and taken it home with me.

Before lockdown, I was excited about making art in a different environment and not reaching for the same tools all the time, to break that habit and exercise a different muscle. My husband, who's also an artist, paints and makes sculptures and does film, so there was this really nice cross-pollination of materials and modes of making. At that time, these reliefs for me were kind of symbollic in terms of the texture relief that I was creating and then also relief emotively at that time. They were totems for me; I was making them at home and hanging them in our living room.

I was really nervous returning to the studio when I felt safe to be around other people. I was really nervous about how the new reliefs would sit with my collaged paper work, because I was very sensitive about the progression and I didn't want to veer off path. I was introducing these wall relief works to my paper collage works and it made sense to me. This was the right direction to go. So I got a blessing from my drawings to continue to pursue this format of making.

It felt good that it was still using paper, which was always a medium in the work but became so specific because it was archives and documents from either my parents at home, my grandparents or my sisters. By recontextualising them, I could think back to all the things that I've learned and the stories I didn’t know. I found out 37 years later that I kind of thought about these archives and documents as a different form of storytelling—not by mouth, but in this three-dimensional form. A lot of the work is about building upon legacy, and a lot of it is homage to family, my heritage, my ancestors and how I was raised.

Nickola Pottinger, Sunday school, 2025 Courtesy of the artist and Mrs. © Nickola Pottinger. Photo: Olympia Shannon

Being a mother impacts the creative process immensely. Did it change the way you thought about creation and the way you conducted your practice?

I had known about this show since before I did [Art Basel Miami Beach with Mrs. Gallery in 2023], so I had some time to think about it. I did two shows back to back and I was exhausted, so I took a break for a few weeks and then found I was pregnant.

The largest work in the show, I began while I was pregnant. I am accustomed to working on the floor, to getting physical with my pieces. I think anyone that paints [or] makes sculpture knows that making art is very physical. I had a hard time; I still got in there, but I moved slow. In the back of my mind, I was really excited to see the work transform after having our baby, and that became a mantra for me. I was like, “I feel like it's going to change the way I work because I'm gonna be in a different state of mind.” That's all I kept thinking about. I was really curious what me post-pregnancy was going to be like.

There's two of the works that are in the show that are casts of my belly. I was contemplating for a while, “Should I cast my belly? Should I do this? Do I want to put this into the work?” It's already autobiographical, so I ended up having my husband go into the studio with me and he cast my belly. That night, the minute the cast was drying on my skin, I started to have contractions. And then two days later I had Zora. I felt like she was always in collaboration with me the entire pregnancy. My mindset was that I was just doing it all for her. So yeah, it was hard, but I wouldn't change any of it.

Do you see your role as an artist as a spiritual one? Do you think of yourself as an artistic agent or as a vessel for ideas?

I feel like I'm the one making the work, but I also feel like there's a higher self I’m communicating with. I'm a vessel in some ways because I'm a container for my own spirit. I'm always trying to connect with spirit. I'm always thinking about what spark of magic or raw emotion comes out in the work, because that feels honest.

Even with the way the work is made, like using my mom's cake mixer that she had me mix black cake every holiday during Christmas, I am comforted that some of my childhood is working with me and I'm working with it. It’s weird working with my younger self and then things get revealed that receded into the back of my memory, which is like always really surprising and a gift at the same time. Sometimes I think about grandparents I grew up with that are no longer here, and I think about grandparents that are still here but live far away. They are very much a part of the work, too, because I try to make work about things that I know. And I know only as much as I do about my personal history and what my family has been through and what we've lived. It’s really important that I'm listening to myself and in this state of channeling those memories and thoughts when I'm making the work.

- Nickola Pottinger: fos born, until 11 January 2026, at the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, Ridgefield, Connecticut