It is now an established fact that colonial violence and extraction are crucial factors in the ecological breakdown and climate catastrophe that are currently affecting us all; and that racial justice and climate justice cannot—and should not—be separated.

The connections between race, the climate crisis and colonialism and the part played by empire building in the current plight of the planet are all key themes that run through Black Earth Rising, an exhibition at Baltimore Museum of Art organised by the British curator and writer Ekow Eshun, who has also written the accompanying book. Both book and show aim to pivot environmental debates away from the Northern hemisphere and a Eurocentric viewpoint and to highlight how this catastrophe and its consequences continue to be experienced most keenly by the populations who were rarely responsible for the crisis in the first place.

“Exhibitions or events around ecological crisis and environmental change are often predicated on experiences in the Northern Hemisphere, so we think about polar ice caps and forlorn polar bears when actually the human experience of climate change is experienced predominantly by people in the Global South,” says Eshun. The curator goes on to point out that “while the industrialised nations of the Global North are responsible for 92% of all excess global emissions, it is the poorer nations of the Global South who disproportionately bear the brunt of environmental degradation”.

“Plantationocene”

Eshun takes particular exception with our fixation on the term Anthropocene—used to define the period dating from around 1950 when it is claimed that human activity began to have a direct and dramatic impact on the earth’s geology and ecosystems. The phrase fails to take into account the fact that, for many peoples, the so-called Anthropocene epoch is simply continuing patterns of environmental destruction that began with 15th century European colonisation. Instead, Eshun prefers the notion of the “Plantationocene”, which foregrounds the historical connections and continued impact of colonialism, slavery and the plantation system and traces the roots of the climate crisis back by several centuries to the vast agricultural estates that characterised the European annexation of the New World.

With the plantation system came large-scale land clearing and extensive deforestation. Eshun also notes that, beyond its physical devastation of local ecosystems, the plantation was a system of power and control that triggered the mass migration and displacement of peoples and the establishment of global networks of goods. “Centuries after its development, the plantation continues to shape a modern world based on the extraction of natural resources and radical economic and social inequalities between the Global North and South. We live in its shadow still,” he states.

An intergenerational line up

The exhibition Black Earth Rising brings together thirteen African diasporic, Latin American and Indigenous origin native American artists who Eshun describes as “artists whose origins lie culturally and genealogically within the Global South or within communities of colour”. This intergenerational lineup includes nonagenarian British Guianan artist Frank Bowling, the late Native American artist and curator Jaune Quick-to-See Smith and British Nigerian artist Yinka Shonibare. They are joined by Kenyan American Wangechi Mutu, along with younger artists such as Cuban born, Miami-based Alejandro Piñeiro Bello; Dominican Republic born, New York based Firelei Baez; and the Brooklyn based photographer Tyler Mitchell.

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Echo Map I (2000)

Baltimore Museum of Art. Purchase with exchange funds from the Pearlstone Family Fund and partial gift of The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. BMA 2020.54

Whether in painting, sculpture, textiles, film or photography all the artists in Black Earth Rising are dedicated to exploring questions of history, power, climate change, and social and environmental justice. But rather than being finger-waggingly didactic, they do so in ways that also emphasise the poetic, the lyrical, the sensory and often the sheer beauty of the natural world.

The sumptuously-coloured Map Paintings made by Frank Bowling in the 1960s and 70s, for example, harness the chromatic drama and vivid sensory impact of colour field painting in order to highlight the forced removal of millions of people and the reworking of geographical roots and connections across the Atlantic. Meanwhile, in his four Earth Kid sculptures, Yinka Shonibare’s jaunty life sized child mannequins, clad in African wax clothes and with globes for heads, combine poignancy with wry humour to address the idea of a younger generation of people growing up dispossessed from the land as a consequence of environmental depredations.

The respite of the natural world

One of the many complexities unpicked in both this show and book is the fact that at the same time as the plantation was a site of brutal subjugation, many Black and Indigenous peoples also looked to the land as a source of resistance or refuge. In the 17th century, more than 20,000 enslaved Americans and Native peoples escaped Portuguese rule to take refuge in the fugitive haven of Palmares, in northeastern Brazil, while in Jamaica communities of runaway slaves and their descendants controlled their own strongholds in the island’s mountainous interior.

For many more, the natural world offered some respite from plantation life through the garden plots or so-called provision grounds, usually situated on poor land on the periphery of an estate. Here at night or on Sundays, in their meagre time away from plantation labour, enslaved people in the Caribbean were allowed—or most often required—to grow their own food. As well as providing essential nourishment, tending crops and cultivating plants offered an opportunity to gather in kinship, and sometimes to speak in banned languages and practice the forbidden religious beliefs of their distant homelands.

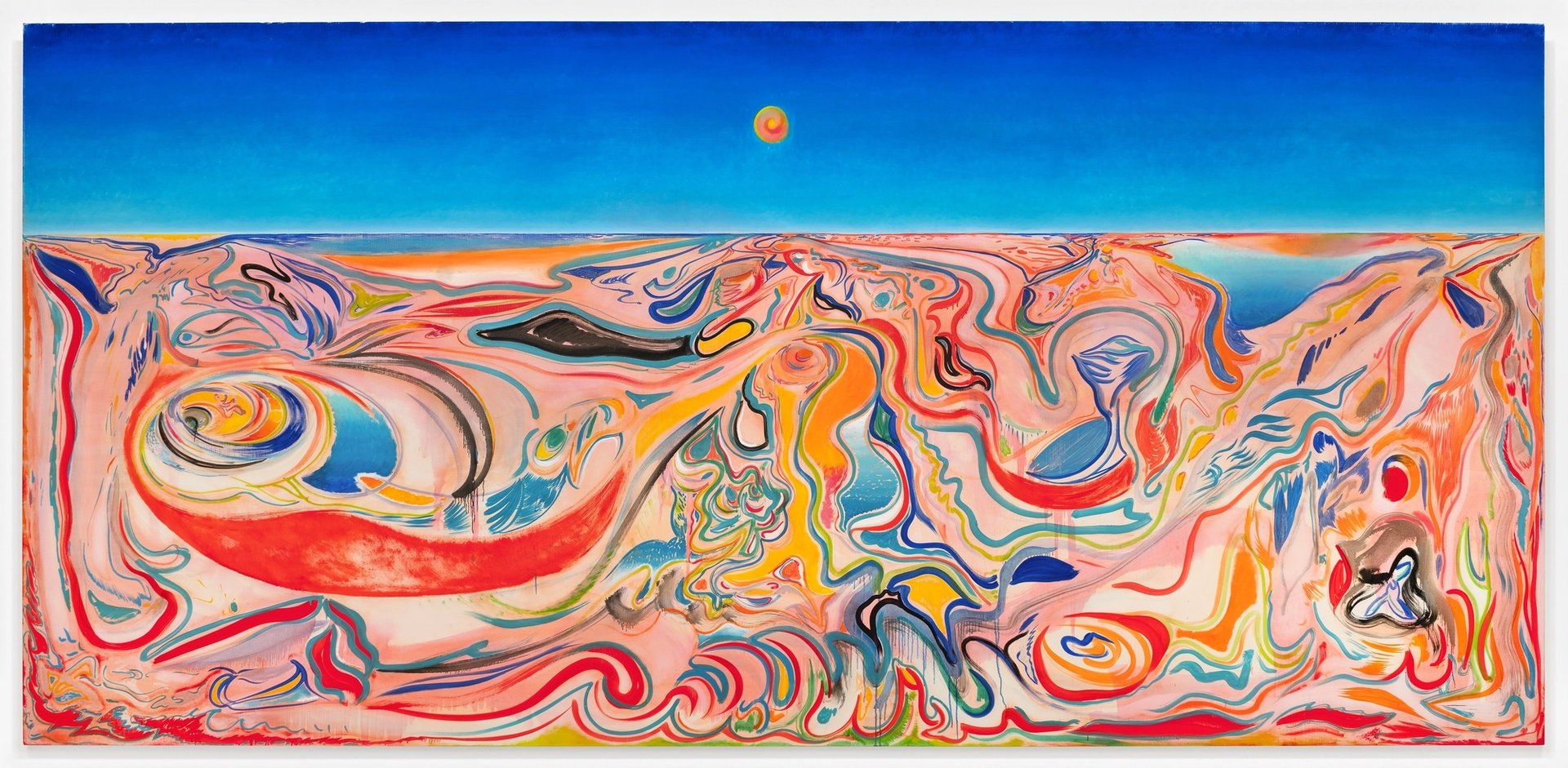

These rich and complicated relationships with the land reverberate through Black Earth Rising. The lush vibrancy of the Caribbean is celebrated in the sheer gorgeousness of Alejandro Piñeiro Bello’s Viajando En La Franja Del Iris (vivid 2024), a nearly 12-foot-long oil painting that offers an immersion in a jungle setting. A sense of wonder at the force of nature also infuses a large woven textile made last year by Otobong Nkanga, where abstract leaf-like forms in rich greens and golds resemble vegetation submerged in water.

Alejandro Piñeiro Bello, Viajando En La Franja Del Iris (2024)

Courtesy the artist and Pace Gallery, New York

Then there is a vivid painting by Firelei Báez which conjures up defiantly disquieting mythological creatures from the folklore of the Dominican Republic, that seep through vivid landscapes to speak of colonial domination but also of indomitable Indigenous resistance. A defiant reclaiming of lost territories is also evident in Sky Hopinka’s video that blends fragmented landscapes with layers of audio, poetic text and music, setting the beauty of the natural world alongside the terrible toll of colonial plunder.

“I’m interested in is artists who are thinking historically but also summoning nature as a site of resistance, as a site of beauty, as a territory that allows them to think beyond an experience of being subjugated and made other, and instead suggesting that nature can be a place of mourning, of fragility, of beauty, renewal, and gathering, a site of possibility,” declares Eshun. The curator also notes that in these multimedia depictions and explorations of the natural world from the redirected perspective of the Global South, “the palette is warmer; the palette is richer. The palette is also full of history and myth and possibility.”

Black soil

New possibilities in depicting, reassessing and responding to the landscape are also communicated in the title of the book and show, which comes from the Portuguese terra preta, meaning “black soil”. This thick, dark, highly fertile topsoil was created in the Amazonian basin by Indigenous civilisations many thousands of years ago by adding a mixture of charcoal, bones, compost, manure and broken pottery to the sparse, sandy Amazonian soil.

An installation view of Wangechi Mutu My Cave Call (2021) at Black Earth Rising

Photo: Maximilian Franz

The black soil helped sustain a flourishing civilization who lived along the Amazon, and by the 1500’s numbered around five million, until the Europeans arrived and decimated their populations. As well as being rich in nutrients, terra preta has also been discovered to hold up to 7.5 times more carbon than surrounding soils and there is now talk of reintroducing it into denuded tracts of the Amazon’s former rainforest.

Terra preta stands as a powerful symbol of the resilience, innovation and wisdom of Indigenous peoples. Like Black Earth Rising, it points to the need to challenge entrenched narratives and perspectives—past and present—and to shift the viewpoint of environmental conversations towards the communities that are uniquely positioned to reflect on the ramifications of colonialism. And, at the same time, this important exhibition and the substance which inspires its name urges us to truly value and appreciate the glory of the natural world and its ability to save us, if we allow it to do so. Let the black earth rise, and the green shoots grow!

- Black Earth Rising, Baltimore Museum of Art until 21 September

- Black Earth Rising, published by Thames & Hudson, $60.00