Reverend Joyce McDonald does not look like all she has been through. As she effervesces with charm and energy, it is difficult to envision the hardships she has endured to arrive at her first museum survey, Ministry: Reverend Joyce McDonald, at the Bronx Museum. Dressed in bright colours and surrounded by her tender clay creations, McDonald tells her truth with a disarming frankness, detailing her history with heroin addiction, HIV and sexual abuse, as well as her current recovery journey from a stroke and sinus cancer.

“It was such an artistic experience, going to the hospital,” the 74-year-old artist says. “I had my camera out. They’re saying ‘recovery is rest’, but for a stroke, they say ‘you better move’, so, I’m moving.” It is tough to keep McDonald down for long. She brandishes a cup. “I love my water in a clear glass,” she says. “You must always be able to see the glass as half-full, not half-empty.”

McDonald discovered ceramics in the wake of her HIV diagnosis in 1995, deep in the throes of drug use and pursuing sex work to survive. In the late 1990s she began an art therapy programme through the Jewish Board of Family Services and was soon connected to Visual Aids, the New York-based organisation that supports HIV-positive artists and artistic production.

“An art therapist gave me a bunch of clay, and said ‘look at this’,” McDonald recalls. “I went into a zone, and I’ve been in that zone ever since.”

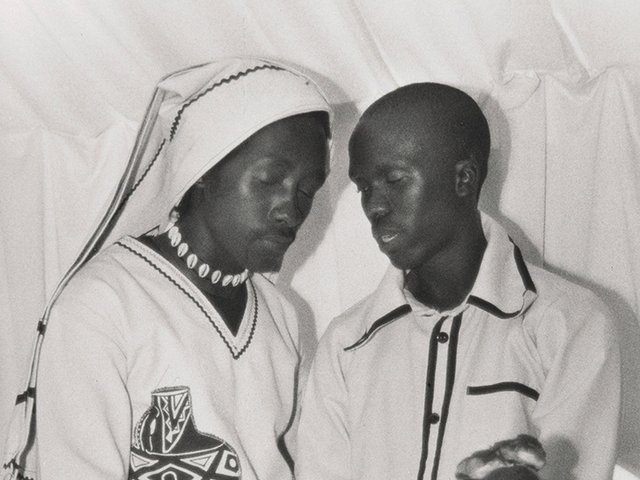

The Family That Pray (2001) is a ceramic sculpture by Reverend Joyce McDonald

Photo by Ryan Page

In 2009, McDonald was ordained a minister at the Church of the Open Door. She has gone on to work as an activist and advocate for HIV awareness, unhoused women and girls, incarcerated women and the Aids ministry of her home church. Her art reflects this penchant for connectivity both as a community doyenne and a loving great-grandmother of seven, often depicting figures praying, embracing or engaging in solemn contemplation.

Her works are in the collections of the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles, the Brooklyn Museum and the CCS Hessel Museum of Art at Bard College in New York State. Her work has been presented at Gordon Robichaux in New York and Maureen Paley in London.

The Art Newspaper: You came to art later in life. Were you a creative kid?

Reverend Joyce McDonald: Yeah, I was artistic. I can remember one picture—I keep saying I’m gonna draw the picture again because it’s so vivid and strong in my mind. My dad worked in the post office and he was a man of God also. He taught us about God, faith, but he would say, “when you gotta do something, take five”. He would always say that, then he would lay on our couch, in his blue-collar uniform from the post office, and he would go to sleep for five minutes. I remember sketching a picture of him on the couch. That’s the first thing I made as a young artist. I would make tents. I would design dolls. I was very creative. I probably would have been a millionaire; I made so much!

My sister Deborah, who was just over here yesterday, brought me a Bible and a sketchbook in one of my stays at the luxury detox. And I just kept reading the Book of Psalms. I didn’t know anything about anything. This was in the 1980s. And then I would draw a picture. I kept drawing it. I did it for 12 to 14 nights because I couldn’t sleep.

Covered with Love (2003) is in McDonald’s Bronx Museum survey

Collection of Michael Sherman and Carrie Tivador, photo by Christopher Burke Studio

The art therapist at the detox asked, “What are you doing with that book?” And I showed her. Art had unlocked the deepest, darkest secrets in my life—the things that happened to me. But you know, I put that book away. I couldn’t even find it until two months ago. I never looked back at the picture. I never looked back at my art. I just started doing that since I had the stroke. Art was like therapy for me. It’s like, you took your medicine, it’s gone.

Since you never looked back at your archive until after your stroke, how was putting this show together at the Bronx Museum? Did it change how you see your work?

You know how some people don’t leave home without certain things in their pocketbook? I always got clay—a bag of Crayola clay. I did a sculpture and it was this woman, but she had a brain on the outside of her head. Looking back, I felt I had new eyes. And then I had to say “Lord, forgive me” because to me, it was solid therapy. In a way that’s a little bit selfish, like “all this is for me”. But I did know that people, when they saw my work, they would say, “I identify with this” or they would have even a different meaning, waiting for me to look at it like they did. I started seeing it like another person looking at it.

Do you feel a responsibility to viewers who are experiencing your work, or is it just raw expression?

It’s almost like I’m unconscious. At the Aids day programme they used to say “If it’s a fire, she’s not gonna run out” because I’d be dead locked in. I don’t hear nothing. I really don’t. I really go into this other place. I’m 74, I’m going to be 75. I always say to God, “99 and a half won’t do”, but I know that whenever I’m out of time, I’m out of time.

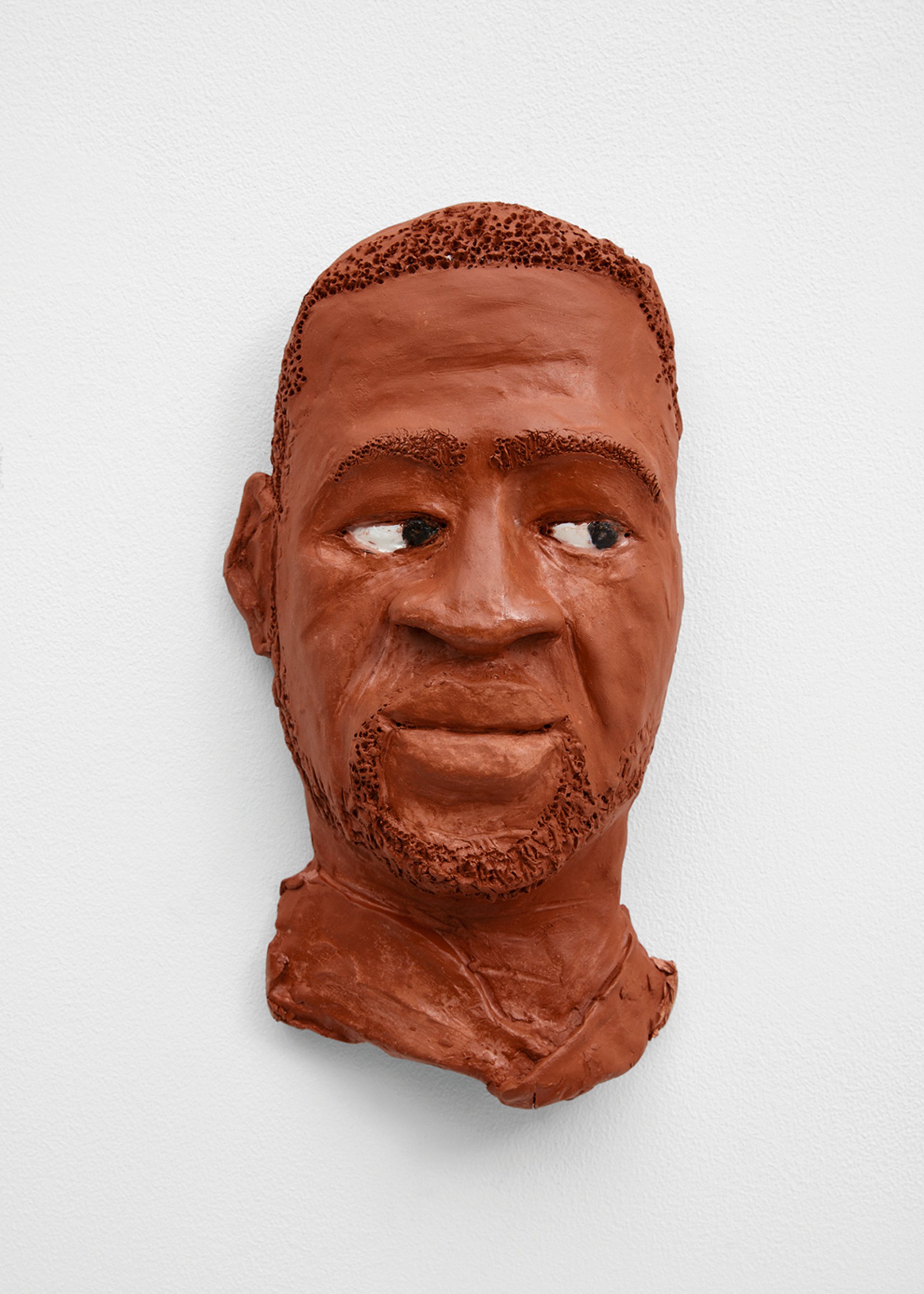

Reverend Joyce McDonald’s Our Lives Mattered (George) (2020)

Collection of Michael Sherman and Vinny Dotolo, Spaghetti Western, photo by Paul Salveson

I see my work now, and it’s hard for me to describe it because I’m not a braggart. When I think about my work, I think, “I didn’t really do this”. But now I have a deeper appreciation for my work. Now I see that in my early works, it was just a lot of pain. I don’t really know how to analyse my work, but I really like when other people tell me what they see. Because sometimes where I see pain, they see concern—they see different. I’m more excited about seeing the story, telling the stories. Nobody has the same story, but they have a lot in a story, or if they don’t have the story, they know the feeling that comes from it.

What is the relationship between your ministry and your art practice?

The relationship was always there. The moment I got saved, God spoke to me on the street and I went upstairs and shot a lot of heroin while I was in church. I don’t remember walking to church to this day. I was just there all of a sudden. I went up and gave my life to God and to Christ. I wasn’t even thinking about getting tested for HIV, because I looked good, I gained weight, even though all the people that I shot drugs with were struggling. They were anybody that was up in Harlem—teachers, principals, bus drivers, people from all walks of life meeting to share needles and probably to hide from their community. I went with the church and I went with this group, the Aids Ministry.

Because there were so many people dying in this community and everywhere, my pastor made that ministry, but I couldn’t wait to get home. I couldn’t wait to get my hands on clay. I had this sense of urgency. That’s what my work always brings. When I do something, it’s a sense of urgency to get in there, wherever it is I’m going. I drew this woman. Her name was Compassion, she had on a purple dress and she’s kneeling, she’s looking up and she has a skinny body laying over her lap. I didn’t know what this was, I didn’t even know why I was making it. When it was all said and done, it represented the moment that I decided to not be a victim, but to be victorious in how I had to live. HIV is not who I am. It’s something I have. And I have quite a few sculptures where I can look at them and say that I was in a very low moment at that moment, but I made it.

Reverend Joyce McDonald’s Beauty in the Midst (Outer Strength) (2023)

Collection of Iris Z Marden, photo by Ryan Page

You identify as a storyteller. What is the difference between a storyteller and someone who tells stories?

There are people who tell stories, then there are people who make stories. When people say, “I don’t have a story like yours” I say, “I don’t want the story I have!” I got kidnapped, molested…I don’t want that story. I’m 74 and I don’t even know my whole story! When I was out there in the streets, I had times where I tried to kill myself because I didn’t want to live. After I became a teenager and things started happening, I prayed that I wouldn’t wake up. I used to be mad. Now I think, “I’m so glad God didn’t listen to me.”

My father always stressed how precious life was. He always used to say, “Whatever thou resolvest to do, do it quickly. Prefer not what the evening may accomplish.” We’d be like, “What is that?” What he was saying is don’t procrastinate. Do it now. Do what you can do now. You don’t know. He drilled into us to live each day as if it’s your last day. Don’t carry stuff, you know?

- Ministry: Reverend Joyce McDonald, 5 September-11 January 2026, Bronx Museum