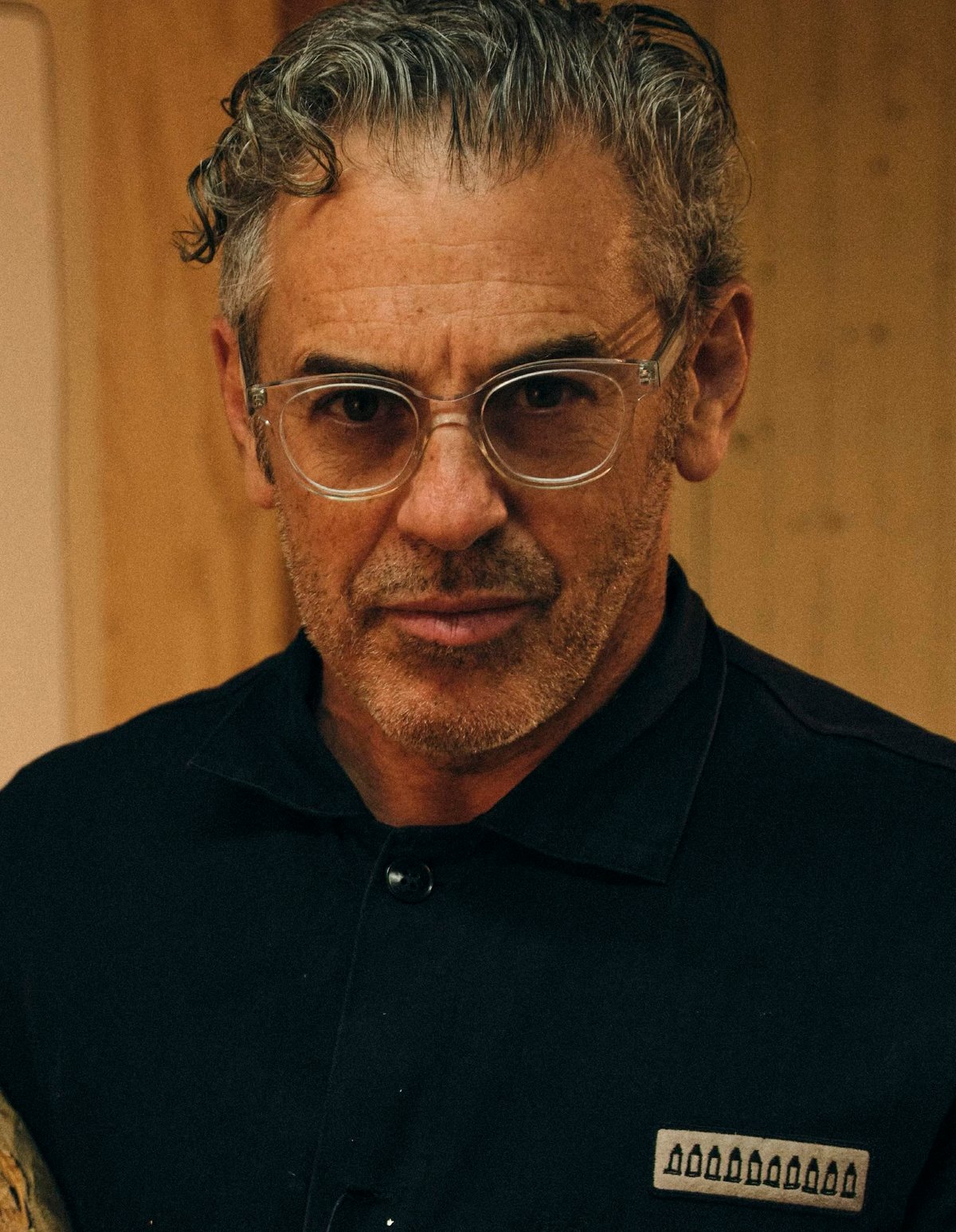

The rules of artist representation are up for grabs in today’s nervously experimental market. In August, a month that brought us the merry-go-round mini-drama of Jeff Koons’s return to Gagosian from Pace Gallery, having left Gagosian for them in 2021, came too a surprising email announcement from a US public relations firm, titled “Tom Sachs: Now Represented by The Lede Company”.

The body of the email clarifies that this is an “agency representation” and its small print notes that Thaddaeus Ropac “will continue to represent Tom Sachs for all gallery and fine art inquiries”, a relationship that has been in place since 1998.

The Lede Company may have overblown a fairly standard—and, thanks to Sachs ending his contract and moving to a different agency, short-lived—PR role, but the brief additional representation still begs the question: where does a gallery end and an agency begin?

In Sachs’s case, promoting clothing deals falls into the latter camp. These include a collaboration with Levi’s jeans and a long-standing arrangement with Nike, for whom his studio has recently created an app with weekly fitness and lifestyle challenges (“participation will help change your life”), all in aid of promoting its Mars Yard 3.0 trainers, which were released in September (retail price tag $275).

Sachs’s practice has long explored paradoxes of consumerism, though such collaborations seem a far cry from his celebrated works from the turn of this century, which included an Hermès hand grenade and a Chanel-branded guillotine. His auction record of $302,400 was for Tiffany Value Meal, a 1998 work that overlaid a McDonald’s meal on a tray with the jeweller’s branding.

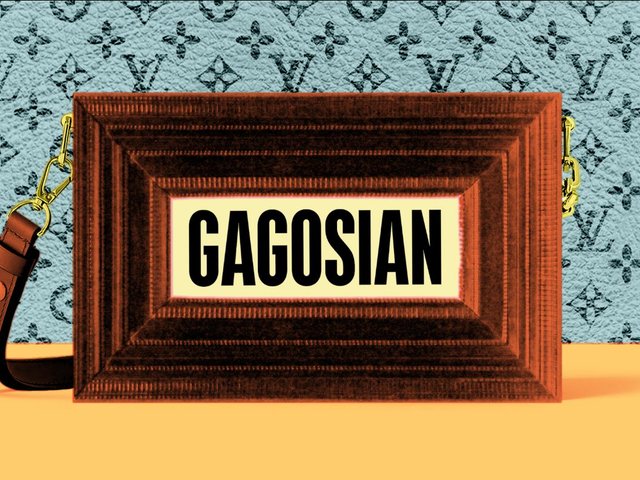

An opportunity for greater relevance

Both Sachs and his agency representatives lean into the artistic and even conceptual nature of his brand collaborations—art has long elevated fashion more than the reverse—and his activities certainly seem more creative than, for example, putting art onto a designer handbag.

At the same time, Sachs is now operating in a different environment and sees an opportunity for greater relevance than today’s art market alone tends to allow. He describes Nike, with its customer base estimated at more than 100 million, as a “megaphone” for his ideas.

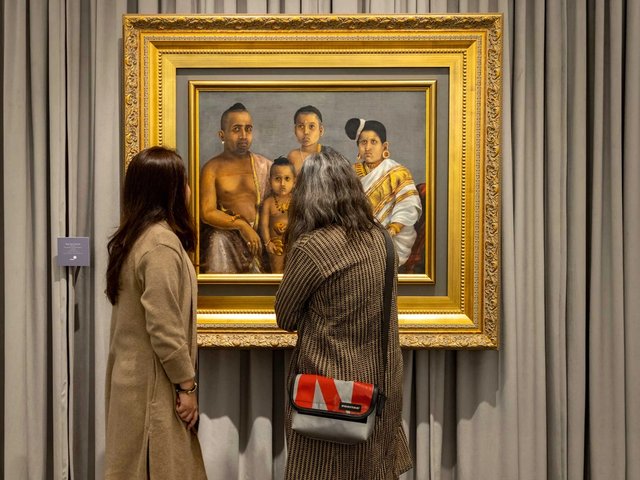

More prosaically, the value of such collaborations with a business such as Nike, whose brand alone is estimated at more than $30bn, is likely to be more financially rewarding than fine art. Sachs has an increasingly ambitious practice to fund and his brand deals likely amount to much more than can be made from 50% of his art sales—at Frieze Seoul in September, Ropac sold one of his sculptures for $90,000.

Ropac’s role is to keep Sachs artistically celebrated, including through international museum shows as well as the art market, and the gallery opened a Sachs solo show (including a coffee and mezcal bar) in its London space this month during the prime Frieze slot. Sachs is also represented by Acquavella in New York.

Without such validation, brands would be less enthusiastic. But the arrival of agencies such as The Lede Company into the constellation of artistic representation underlines the latest reality, in which the market is limited, financially and promotionally. As Sachs tells The Art Newspaper, “Working with Nike is motivated by the idea that art takes many forms, and that the conventional museum-gallery-collector pipeline known as ‘the Art World’ isn’t the most important thing about art.”