The University of Pennsylvania’s Penn Museum in Philadelphia will open its new, 2,000-sq.-ft Native North America Gallery on Saturday (22 November) after two years of planning and development.

An all-day opening celebration—featuring performances, workshops, talks, demonstrations and storytelling—will inaugurate the new long-term exhibition with a strengthened focus on Native American histories. The gallery replaces its previous iteration, an exhibition titled Native American Voices: The People—Here and Now, which opened in 2014 but did not fully reflect the four regions of Native American tribes it sought to present.

The preceding gallery was curated by the museum’s Lucy Fowler Williams in collaboration with around 80 Native American consultants. But the space felt “fragmented”, Williams says. This time around, she and co-curator Megan C. Kassabaum—with their backgrounds in cultural anthropology and anthropological archaeology, respectively—worked closely with eight Native American curators, who helped determine which stories should be told in the exhibition.

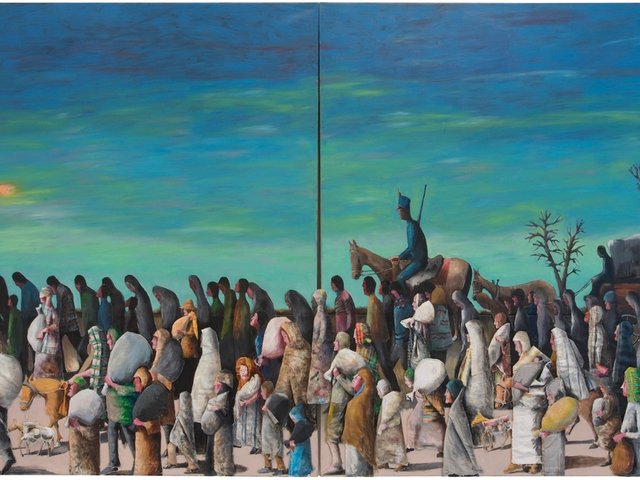

“We made a conscious decision to not shy away from representing the moments of rupture, loss and betrayal that Native communities have faced; these stories are essential,” Williams says. “But we also wanted to highlight resilience and strength within those histories.”

On display in the Northwest section, a Naaxein (Chilkat Tlingit blanket) ceremonial robe Photo: Kellie Bell for the Penn Museum

Rather than calling Native curators “advisers” or “consultants”, the museum was “intentional about recognising them as curators”, Williams adds. “The work they were doing was curatorial, and we wanted that reflected in how we referred to them—not just as a symbolic shift but as a structural one. That language matters; it shapes how everyone else in the institution sees and treats the collaboration.”

Leaders at the museum hope that closer partnership with Native scholars will set a benchmark for how institutions work with tribes, help to advance guidelines around ethical museum practices and spark constructive conversations around repatriation that prompt visitors to engage with complexities around colonialism, cultural resilience and the ethical stewardship of Native objects.

“This was an opportunity to think about how we can put these stories in conversation with our collection and the historical record, then make sure the voices of contemporary Native communities are leading the charge,” Kassabaum says. “I hope that, years from now, visitors will see that those relationships have also matured and changed.”

The consulting curators are Jeremy Johnson (Lenape, Absentee Shawnee and Peoria), cultural education director for the Delaware Tribe of Indians; RaeLynn Butler (Creek), culture and humanities secretary for the Muscogee (Creek) Nation; the archaeologists Beau Carroll (Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians) and Mary Weahkee (Santa Clara Pueblo); the art historian Nadia Sethi (Alutiiq/Ninilchik); the Zuni cultural specialist Christopher Lewis (Badger Clan and Corn Clan); Huna Indian Association culture heritage director Darlene See (Tlingít); and the tribal historic-preservation officer Joseph Aguilar (San Ildefonso Pueblo).

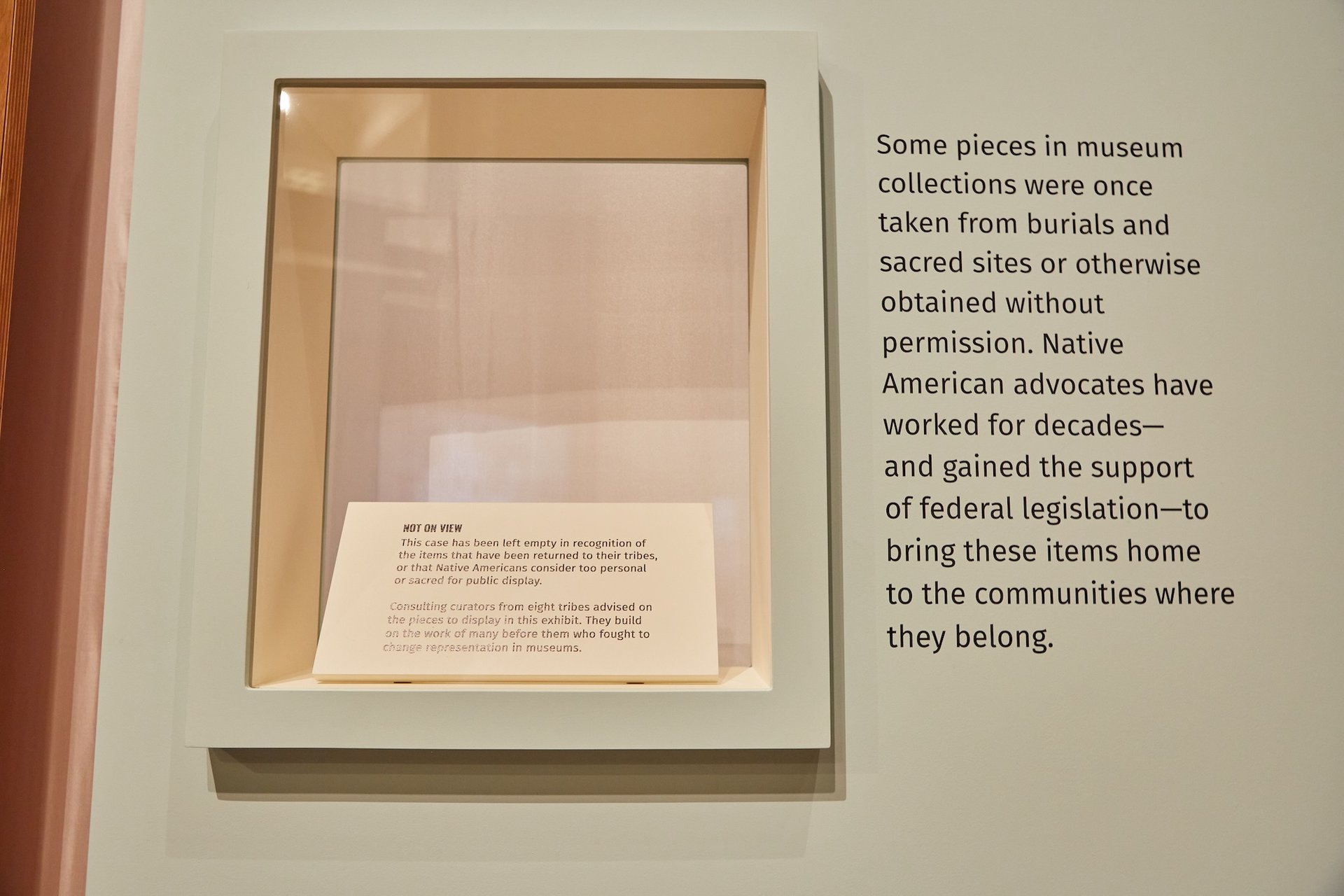

An empty display case provides a moment for thoughtful reflection about repatriation and honouring Native views about which items are appropriate for display Photo: Quinn R. Brown for the Penn Museum

Aguilar, a University of Pennsylvania alum who also worked on the 2014 setup, says the former gallery was “outdated but still comfortable”, given that there were few museums where he “felt welcome as a Native person”. For the gallery’s current iteration, Aguilar helped conceive the presentation of an empty vitrine, the first thing visitors encounter in the new gallery. It is a gesture recognising both ongoing repatriation efforts in museums and the objects that tribes feel are inappropriate to exhibit.

“The Penn Museum has many culturally sensitive materials that, in the eyes of the communities, should not be displayed,” he says. “Rather than omitting them without reference, we wanted to acknowledge them. An empty case says more than nothing at all. It serves as a teaching moment for visitors. Repatriation was also an important part of the narrative we wanted to bring across.”

Over the years, the Penn Museum has been scrutinised for its repatriation processes. Several objects in its 160,000-piece North American art collection, which represent Native American and First Nations Canadian communities, remain under review. Ever since the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (Nagpra) was enacted in 1990—mandating that federally funded museums in the US make their holdings available for repatriation requests—the museum has worked with more than 130 tribes to complete 56 repatriations, resulting in the return of more than 1,600 human remains, funerary objects, items of cultural patrimony and other holdings.

Aguilar says that his experience as a co-curator of the new gallery has “fulfilled” his expectations for how museums should engage with Native communities. “There’s so much museums can do. They have the capacity—but it’s not about resources, it’s about commitment,” he says. “This project is an example of a museum moving in the right direction. Museums have to partner, not just collaborate; there has to be an equal stake in stewardship of collections or the creation of exhibitions. Real investment in communities—financial, programmatic and long-term—is necessary.”

Multimedia offerings and hands-on interactives play a major role in the new Native North America Gallery Photo: Quinn R. Brown for the Penn Museum

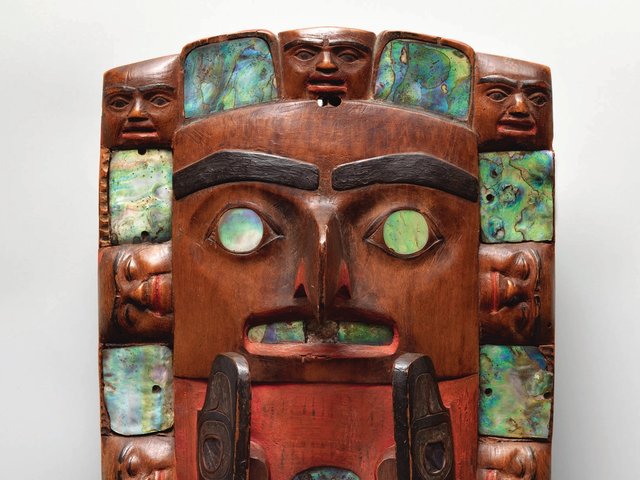

The Native North America Gallery centres first-person Native perspectives, examining the political, linguistic, religious and artistic nuances that shape tribal cultures. It mixes contemporary art, such as works by the artists Brenda Mallory (Cherokee) and Preston Singletary (Tlingit), with around 250 historic and archaeological objects—including replicas of fragile materials. The gallery also corrects the interpretation of objects that were previously inaccurately labeled in the collection database, such as a “shaman’s wand” that Native curators determined was actually a doll.

There are elements of the gallery that aim to expand on how tribal regions have been historically represented in museums. For example, rather than focusing on pottery to represent Southwestern tribes, the curators decided to feature infrequently seen objects that hold equal ceremonial and practical meaning. These include garments and baskets made of yucca and fibre that relate to the tribes’ relationship with the high-desert environment and its plants. In addition, the gallery features interactive elements, like stations for learning words in Native languages or traditional weaving techniques.

The museum’s director, Christopher Woods, says the unveiling of the gallery in advance of the 250th anniversary of the founding of the US next year, and during Native American Heritage Month, provides an opportunity for visitors to “reflect on American history through Indigenous perspectives” and “amplify the importance of Indigenous values and communities that we know inhabited this land long before the nation was founded”.

Woods adds that the museum remains “steadfast” in its mission, despite cuts to federal funding for the arts under president Donald Trump's administration. The Penn Museum received numerous donations to realise the project, including from the Boston-area real-estate mogul Lewis Heafitz and his wife, Ina. Woods believes that donors saw the current political situation “not as a setback due to the world changing around us but as a call to action”, recognising the importance of “inclusive, historically grounded storytelling as national narratives are being contested and rewritten”.