Andrew Lambirth’s approach in The Uglow Papers is a curious one. The art critic and writer eschews a conventional monograph on the British painter Euan Uglow (1932-2000) by bringing together a selection of contributors and, through a series of memoirs or papers, allowing them to speak for themselves. It is an uncomplicated tactic in many respects, even allowing for authorial or editorial interventions. Yet the conversational nature of these contributions—made in person, by phone, email or letter—form a series of observations and recollections that, together, weave a rich and deeply personal celebration of the man, his work and his teaching.

In an understated example of form and content finding a common resonance, the author’s pared-back introduction brings clarity to Uglow’s complex creation of crisp shapes and bold colours, his measured approach to painting. It provides an important frame of reference for readers prior to the around 30 personal accounts and memories that make up most of the following text. A helpful glossary of names at the back of the book ensures readers know who people are and how they relate to the artist.

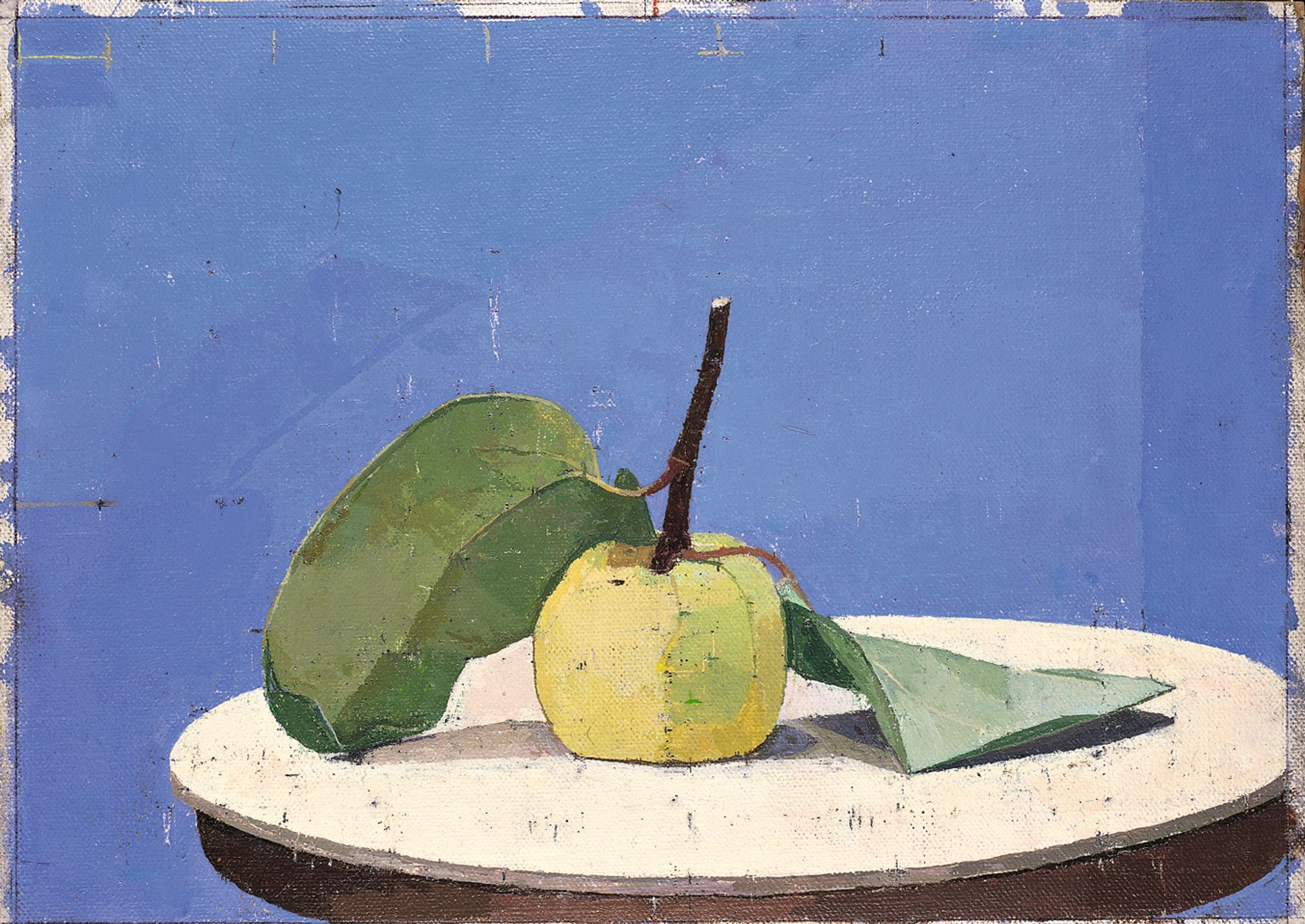

Quince, a work the artist completed in 1998, two years before he died © The Uglow Estate

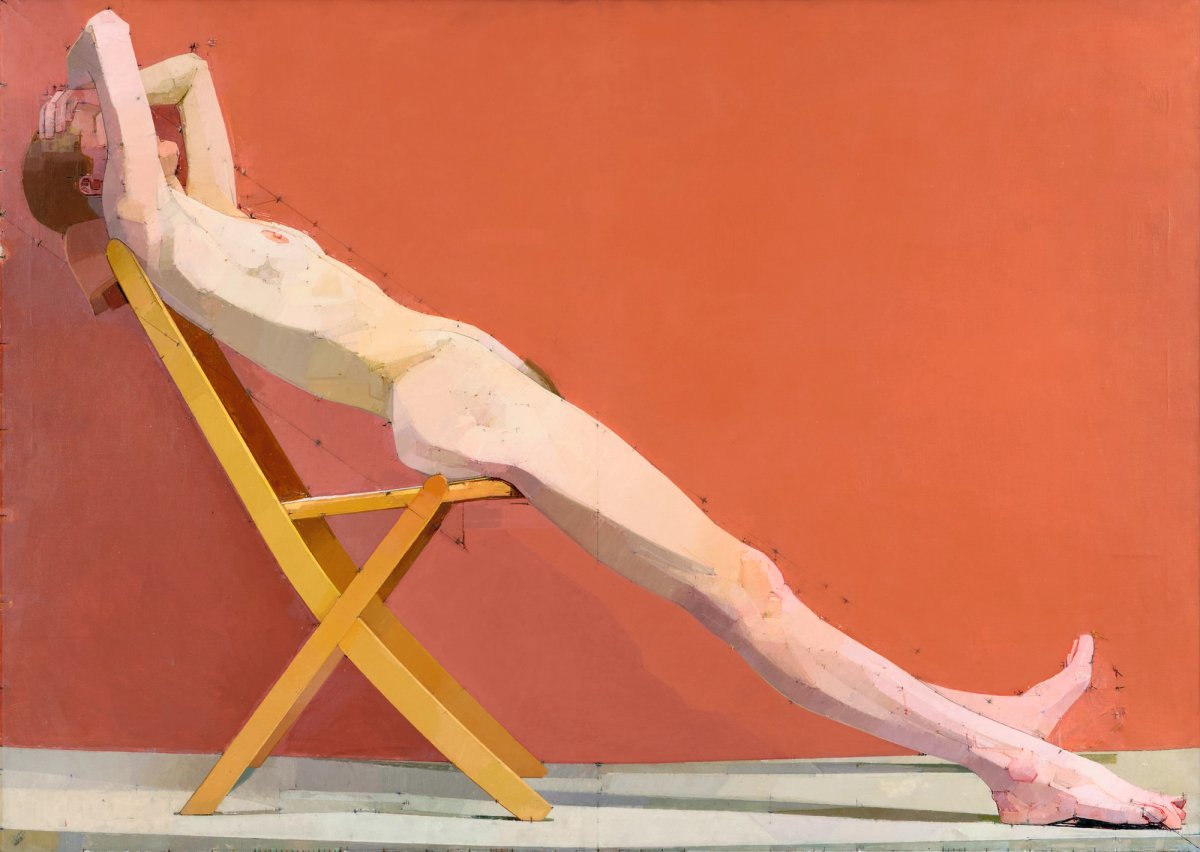

London-born Uglow was the middle child of three siblings and showed a devotion to art throughout his wartime childhood. He attended Camberwell School of Arts and Crafts from the age of 15, graduating in 1948, followed by the Slade School of Fine Art, graduating in 1954, going on to teach at both. He married in 1963, but Uglow’s exacting temperament and rigorous studio routine were not conducive to a successful marriage and the couple separated three years later. It was from his mentor William Coldstream (1908-87) that Uglow developed his own approach based on Coldstream’s “dot and carry” method of painting. With disciplined enquiry and a fierce attention to geometry, Uglow structured controlled still-life compositions and paintings of nudes bursting with potent emotion such as The Diagonal (1971-77) or Pyramid (1993-96). The painter Anthony Eyton remembers Uglow’s strong sense of purpose, ambition and moral courage; Craigie Aitchison (1926-2009), a good friend for half a century, called him a radical painter of great clarity, someone whose traditional skills still allowed for modernity; the artist Philip Sutton, meanwhile, recalls many personal details of visits and shared meals that enrich and enliven the story of Uglow as artist and friend.

Laetitia Yhap was a student at Camberwell (1958-62), where she was taught by Uglow and remembers sitting for him in colourful detail—the inadequate heating in the winter studio, elaborate meals such as jugged hare, and the value of friendships. This is the sort of minutia that helps to build a more rounded picture of the artist. The memories of Tony Rothon, a student at the Slade (1967-73), where he was also taught by Uglow, relate to methods, materials and expectations. Students of Uglow’s “F-Studio” (Figurative Studio) sessions were, Rothon suggests, signed up as if to a cult. Punctual attendance was essential, and measurement was by hand, eye and memory.

Those recollections regarding Uglow’s social and domestic situation may be anecdotal but are largely consistent across the contributors. There was the Sunday night “open house”, a lively affair by all accounts. The painting conservator Martin Wyld remembers Uglow cooking enthusiastically, and his love of good wine, as well as shared games of darts and cricket and a favourite restaurant in Florence. Mark Dunford first met Uglow as an 18-year-old undergraduate at the Slade (1982-87). As well as recollecting some architectural details of the F-Studio and the relentless intensity of Uglow’s teaching, Dunford also recalls the importance of a more social engagement, when Uglow would share books and food, including one occasion when he taught them how to clean, prepare and cook calamari.

Studio with a social side

Another Slade student was Simon Chambers (1992-94) who recalls the F-Studio not as a life room, but as a painting studio committed to a sustained engagement with the appearance of human beings through perceptual painting. His recollection is that Uglow’s teaching was subtle. Friday drinks and discussion were an important extension of the week’s work and the F-Studio Christmas dinner was a generous and rumbustious affair.

Uglow’s last trip abroad was to Colmar in the Alsace region of France in 2000, to see Matthias Grünewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece (1512-16). He was extremely ill by this time and travelled with friends to fulfil his lifelong ambition to see the work. It showed incredible courage on his part to face this portrayal of agonised death at the end of his own life. A study of the altarpiece was the last drawing in Uglow’s sketchbook.

The book is not only about Uglow’s personal life and there is much to be gleaned from the myriad accounts of his teaching and painting. Chris Bennett remembers from his time at the Slade (1980-84) Uglow’s knowledge of Egyptian geometric construction and his focus on pinning down the optical experience. Colour was important too in the representation of volume, as can be clearly recognised in the shaded and faceted paintings Lemon (1973) or Quince (1998). James Lloyd, who was taught by Uglow at the Slade (1994-96), remembers long poses of eight or even 12 weeks and recalls him talking about the model architecturally, even using terms such as “plan” and “section”.

One of the more poignant stories of the book is recalled by painter Laura Smith, who was taught by Uglow in his last years at the Slade and modelled for him. She sat for him in 1999 and Uglow worked on a drawing for eight months on Sunday mornings, until he was too ill to continue. Smith confesses, decades later, that she would dearly love to see this drawing one more time.

There is an opportunity in this new volume to read an adapted version of Lambirth’s 2014 essay on Uglow’s drawing technique. It is useful for the reader to note that Uglow’s dots-and-dashes “Morse code” system of drawing was often accompanied by what Lambirth calls “wristy scribble”, and that his drawings could either begin from an idea or be a process of uncovering. Perhaps it is these tensions that lend his work so much energy and passion. Two short texts by the artist himself share his thoughts on watercolour and oil paint. The former gestures to the sophistication of the medium, while in the latter, Uglow talks about the “aliveness” of the medium, which seems to be what attracted him to it.

The risk of including so many individual contributions in a single publication is that it becomes somewhat fragmented or disjointed. Yet Lambirth’s use of a loose chronology to structure the book, his inclusion of the small details of each contributor’s relationship to the artist, as well as the times, locations and methods by which communications took place, means there is a secure framework to pull this disparate material together, while, in tandem, echoing the precision of Uglow’s approach to painting. In this way, the book’s architecture echoes its content, in a manner that leaves the reader feeling they are part of that F-Studio conviviality and closer to an understanding of Uglow as a committed artist and generous individual. It is a tremendously satisfying read.

• Andrew Lambirth, The Uglow Papers, Modern Art Press, 320pp, 170 colour and 10 b/w illustrations, £30 (hb), published 13 May

• Beth Williamson is an art historian and writer. Her book, A Cultural Biography of William Johnstone: The Making of British Modern Art, will be published by Edinburgh University Press in 2026